It should be child's play to accept that some modern art is rubbish

A Critical View: Some modern art is rubbish; All the oils you own yourself; Thank skeuomorphs very much

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I confess that I didn't start watching The Shock of the New, Robert Hughes's landmark 1980 series about contemporary art, with entirely pure motives. BBC Four have been rerunning it as a tribute to the art critic, who died last month – and apart from a desire to see whether it stood up as well in fact as it did in fond memory, I also suspected that it might provide a shillelagh with which to belabour some regrettable tendencies in modern art-television. In truth the results were mixed. It's very good, because he is, but it's also startling to discover just how patient audiences were assumed to be 30 years ago (or, possibly, how atrophied our attention spans have become now). Quite long sequences unfold as simple montages of illustration and music. And although this has its virtues, you'd be hard pressed to argue that it's a sophisticated use of the medium. I also discovered – a little to my surprise – that Hughes began with one of those "In this series..." intros which so disfigure modern partworks – though he had the courtesy to keep his to around 30 seconds and he wasn't filmed on a mountain top as he delivered it.

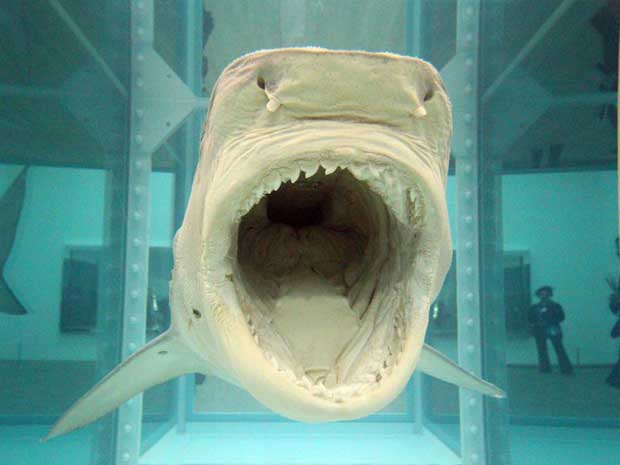

One thing made me cheer aloud though – and it came during that opening introduction. Hughes explained the start and end point of his 20th century (roughly 1880 to his present day) and then characterised it as a period which had left behind it "some of the most challenging, beautiful and intelligent works of art that have ever been made... along with a great mass of superfluity and rubbish". And it wasn't the first half of that statement that made me cheer, but the second. Absolutely anyone could come up with the first bit, after all. You've been hired to present an eight part series on modern art and you – or your producers – may be a little anxious that the audience will be wary. What else are you going to do but promise that there are treasures in store? That's the thinking that seems to prevail now, when the presenters of big intellectual series often open up by brandishing their greatest hits and highlights.

But the truth is that it's the second remark that really sinks the hook in you. It acknowledges, without any fuss at all, that the unavoidable corollary of any superlative is all the stuff it rests on. And it hints that this is a man who knows the difference between good and bad art, and won't be nervous about pointing it out.

My cheer was possibly a little louder than it would otherwise have been because I'd just been reading two newly published guides to modern art – Why Your Five Year Old Could Not Have Done That (which is aimed at adult readers) and What is Contemporary Art? (which is intended for children). Both of them are intended to bring the light of contemporary art to nervous or suspicious outsiders. And they're not at all unusual in assuming that proselytising in this field has to depend on praise and rapture. I don't think either of them contains a passage in which a work is criticised for its failings, or – indeed – any suggestion that work A might be of more value than works B or C. It's almost as if the acknowledgement that a work might fall short of its own ambitions – or achieve them and still be banal – would start a hairline crack that might eventually spread and bring the whole edifice down. They're wrong though. Nothing is more likely to put people off art than the feeling that it's impermissible to dislike it, few things as empowering as the permission to discriminate. It wasn't Hughes's enthusiasm alone that made him such a riveting broadcaster but the reassuring knowledge that not everything automatically received it.

All the oils you own yourselves

Next week sees the completion of an admirably quixotic enterprise of scholarship, the Public Catalogue Foundation. When the photographers pack up their equipment at the National Football Museum in Manchester next Thursday the PCF will have fulfilled the mission it set itself more than 10 years ago of recording and cataloguing every oil painting in public ownership in the UK. The final tally is 210,000 works of art from 2,800 institutions and galleries. And later this year they hope to have the entire collection online (via bbc.co.uk/yourpaintings), searchable by artist, title and subject matter. Take a look. They're yours.

Thank skeuomorphs very much

A skeuomorph, you may be interested to know, is an ornamental design element that owes its existence to a functional one. So, your vinyl satchel (say) includes press-moulded stitching lines, because satchels were made of leather and had to be stitched. I learned this word because Apple, while despising skeuomorphs in its hardware, appears addicted to them in its software, and this makes some design purists cross. I'm undecided. The scraps of torn-off page you can see on Calendar are kitsch and silly. But the little judder that some unsung genius programmed into the virtual second hand on the Apple desktop clocks? I'm sorry but I'd hate to lose that. Sometimes a skeuomorph isn't a fake. Sometimes it's literature.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments