Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

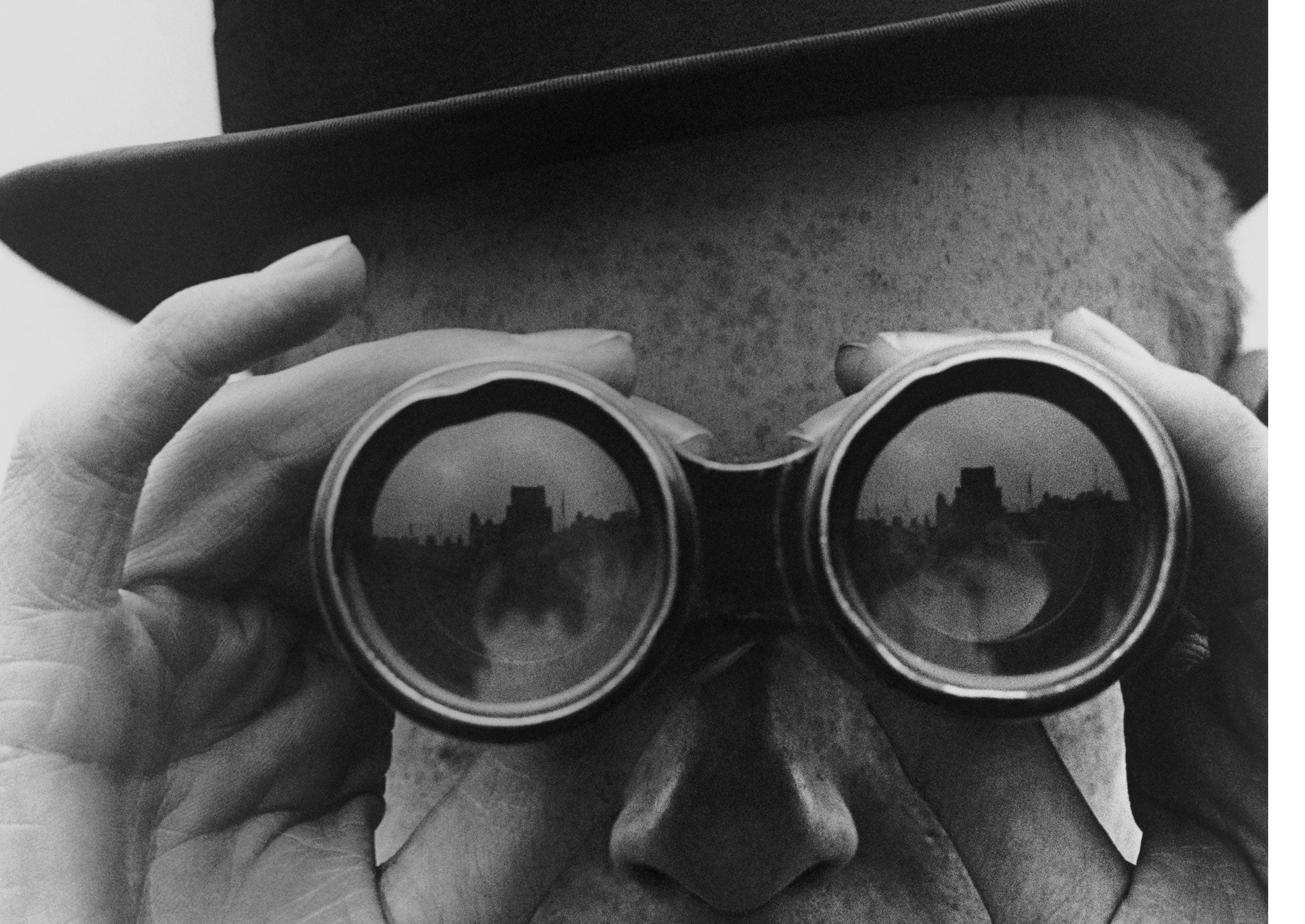

Your support makes all the difference.Some 500 authors have this week spoken out about the capacity of the intelligence agencies to spy on millions of people’s digital communications. They have a point when they argue that this is “turning everyone into potential suspects”. Yet maybe the authors should look more widely than the obvious spying of state surveillance. More worrying is the tendency for the authorities to recruit us all to become spies of each other – to view every innocent interaction through the prism of distrust and suspicion.

Remember how Othello, who “thinks men honest”, is driven to distraction and ultimately murder by listening to unfounded rumours planted by Iago. Tragically today we have a whole army of people encouraging us to be suspicious.

Look at what they have been up to in recent weeks. No longer satisfied that society now routinely suspects that any adult being nice to children might be Jimmy Savile in disguise, Sue Berelowitz, the Deputy Children’s Commissioner for England, wants us to be suspicious of children’s treatment of each other, claiming that child-on-child rape is part of everyday life. Irresponsible hyperbole about “chilling” levels of sexual “sadism”, rife not just in inner-city gangs but “affluent middle class areas” and “church schools”, can only lead to paranoid parents becoming destructively suspicious of every innocent teen romance. Mums everywhere will worry that while Henry might look like the nice boy next door, who knows what he’s subjecting Sophie to on a date. Dads could be forgiven for locking up their daughters to protect them from the rape and pillage allegedly occurring at every school disco.

Or there’s Clare’s Law, which allows us all to apply to the police for information on a partner’s history of domestic violence. Of course domestic abuse is vile, but do we really want a society in which before we embark on a relationship, we rush off to check whether our loved one is really a secret wife-beater? And then there’s the supposed hidden epidemic of modern slavery. Based on one high-profile but distinctly odd episode, the Home Secretary Theresa May declared that slaves are “cowering behind the curtains in an ordinary street…”, working in our local “factories or nail bars”.

But my gold medal would go to Keir Starmer, until recently Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP), who would have us locked up for failing to report the dark, malevolent suspicions we might have about our fellow-citizens. Last month he suggested introducing mandatory reporting of any suspicions of child abuse, arguing that “if you’re in a position of authority or responsibility in relation to children” and “have cause to believe that a child has been abused, or is about to be abused, you really ought to do something about it”. Or else! He blithely concluded that a criminal penalty such as “a short jail sentence or a fine” for failing to report would “focus people’s minds”, while there should be “immunity for individuals if they did report”. Note the catch-all wording: “If you have cause to believe a child … is about to be abused”. Surely such loose talk is an incitement to rush to pick up the phone, “just in case”, or even just to cover your own back.

Already professionals are weighed down by a plethora of statutory guidelines about reporting abuse. While you can’t guarantee a physics teacher has a physics degree these days, you can be damn sure they have been tutored in a checklist for signs of abuse. How much more corrosive to threaten Mrs Smith with Starmer’s mind-focusing stint in prison if she doesn’t dob in her fellow English teacher Mr Jones who, according to schoolyard gossip, is spending too much time with student X. Giving her help with literacy? Offering pastoral advice? Something more sinister? Being coerced into assuming a worst-case scenario can only lead to an escalation of life-shattering false allegations. And now that we have a panic about children abusing their peers, playground duty will be more Vice Squad than educator.

Such a climate puts everyone on their guard, fearful that their actions might be misinterpreted as dodgy. If many parents are already nervous about taking a bruised child to the doctors in case eyebrows are raised, one can only guess at how Starmer’s “compulsion to report” would ratchet up the pressure on professionals to eye parents suspiciously, to see every cut and graze as “evidence” of wrongdoing (rather than for example the consequence of boisterous play). This could also mean parents withdrawing from seeking help, even when they need it. Would you dare confide your worries about your infant not eating to a health visitor if you knew she might report you for neglect?

Despite Starmer’s inference of under-reporting, reports of child abuse are on the rise. Hardly surprising: the “better to report than be sorry” mantra has now seeped into broader culture. At the start of the year, the NSPCC’s TV advertising campaign urged us all to report any concerns we might have about a child, with the slogan “Don’t wait until you are certain”. Encouraging us to run to the authorities even when we aren’t certain has arguably led to excessive reporting, which in turn might dangerously clog up the system. With too little distinction between vague suspicions and serious allegations, authorities can easily be distracted from identifying children for whom there is a genuine, concrete threat.

Too many of these initiatives are likely to be counterproductive. Take for example Heath Secretary Jeremy Hunt’s plans for a “statutory duty of candour” within the NHS. In the wake of the Mid-Staffs scandal, Hunt has declared that: “We want a signal to go out to every trust board and chief executive…to every doctor and nurse – if you are in any doubt at all, report.” (my emphasis). But surely one guarantee of ensuring that health professionals pick up on and rectify neglect is for staffs to work together closely in an atmosphere of mutual trust. How can you trust your colleagues if hospitals are hotbeds of anonymous finger-pointing and snitching? Won’t Stasi-like spying through the paraphernalia of confidential whistleblower hotlines more likely result in a fragmented, paranoid workforce? This must demoralise team spirit and destroy any semblance of solidarity; it hardly seems a way to encourage a mutual commitment to shared values of care and compassion.

Indeed, compassion can die when procedures are built on suspicion. Take officialdom’s mean-spirited attitude to community care of the elderly. Because the elderly are categorised as “vulnerable adults”, anyone who offers “care and companionship” is asked to prove that they aren’t seeking to “take advantage” of their “position of trust”, and is subject to those invidious criminal-records checks. Some councils even demand that elderly people volunteering to telephone other elderly people for a chat be subjected to checks. Meanwhile, volunteers driving old people to the shops are advised to “always work in twos”, so they can keep an eye on each other. Poison – drip, drip.

The problem is that once we have minds suspicious enough to view actions motivated by human kindness as malign, there is no limit to imagining what evils go unreported. The authors are right to note that “a person under surveillance is no longer free”. But perhaps more invidious and threatening to freedom than spying agencies spying on us is the corrosive outcome of us all having suspicious minds.

It’s time to shine a light not just on M15 or the NSA but on a culture in which we’re encouraged to live fearful lives, always having to guard against allegations, forever monitored or spying on others on pain of punishment.

Claire Fox is the director and founder of the Institute of Ideas

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments