Israel's mowing of Gaza's lawn is an unjust war

A Just War must have a reasonable prospect of success. But Israel is locked into failure

A 10-year-old boy called Ibrahim Dawawsa died needlessly on Friday. He was playing in a yard when an Israeli drone hit the mosque next door. The strike was in retaliation for a few ineffectual rockets fired into Israel some hours earlier by Palestinian militants to mark the end of the three-day ceasefire in Gaza.

Why, you might wonder, were some Palestinians so eager to restart the war after the mighty Israeli army had ceased its ferocious month-long bombardment? But that question fails to understand a fundamental clash of perspectives between the Israelis and the Hamas militants who control Gaza.

Israel's demands are short term. It wants an end to violence. Its military objectives have been to destroy Hamas's ability to fire rockets and blow up the tunnels through which militants can enter Israel to launch attacks.

The perspective of Hamas is more long term. For them a mutual cessation of violence is not enough. They want an end to the eight-year blockade which prevents a huge range of goods – A4 paper, crayons, shoes, crockery, wheelchairs, hearing aid batteries, pasta and even coriander – from entering the strip of land which has been described as the world's largest open prison. Israel says the blockade will not be lifted until Hamas disarms. Meantime, the retaliation will continue.

There are six classic criteria for a Just War. Your cause must be just; you must act with good intentions and have legal authority. More problematically for Israel, the means you use must be in proportion to the end you seek to achieve. It is on this that world opinion has found Israel wanting. The casualty figures confirm that. A quarter of the population of Gaza has been displaced, with 206,000 huddled in UN shelters. Almost 2,000 Palestinians have been killed, three-quarters of them civilians. The death of Ibrahim Dawawsa took the number of child casualties to 420.

But there are two other key Just War criteria. You must have a reasonable prospect of military success. And all other ways of resolving the problem must have been tried first. On both of these Israel's record is questionable.

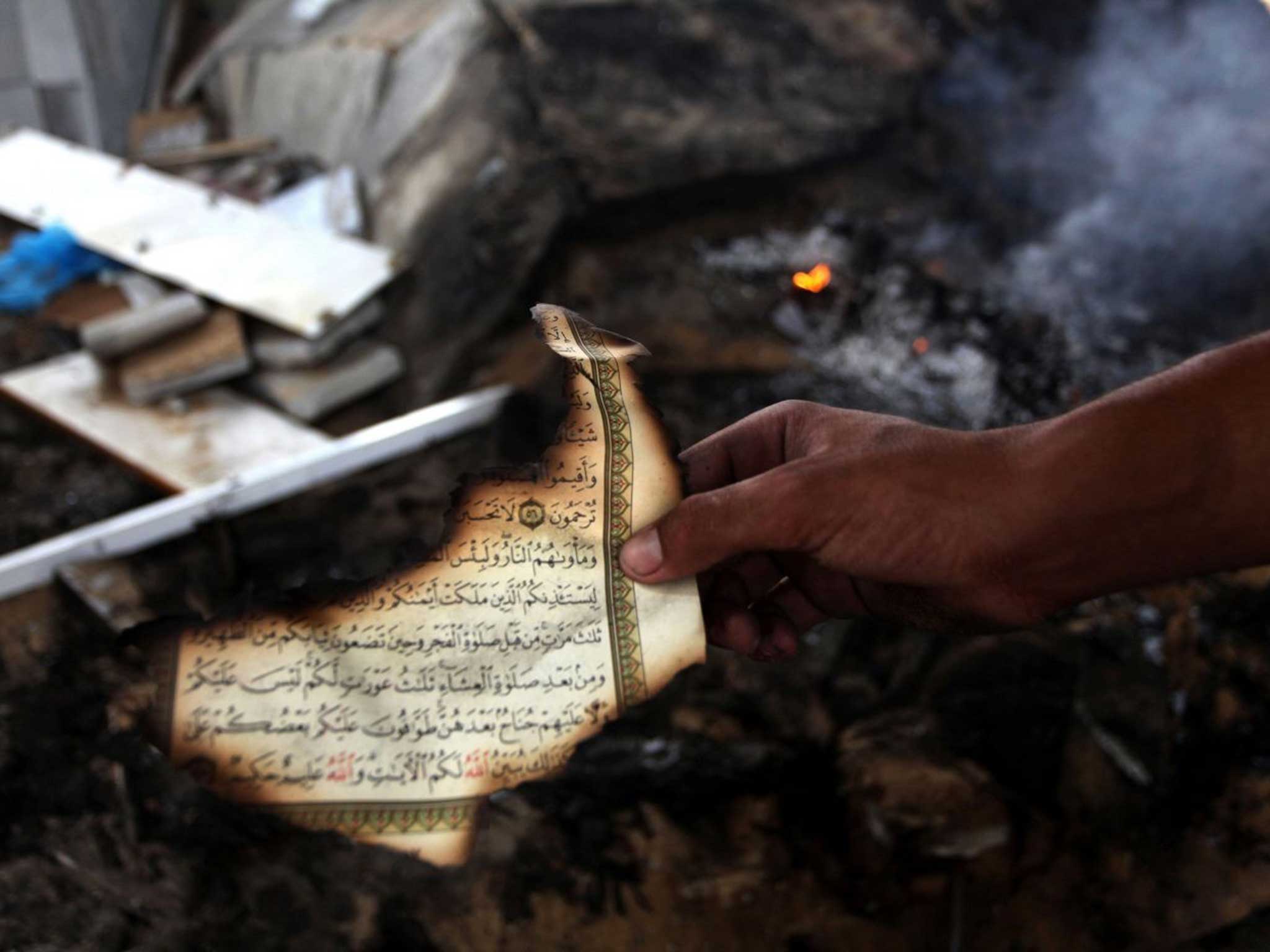

This is the fourth war in Gaza in a decade. Israeli military strategists talk, chillingly, of "mowing the lawn". Even leaving aside the morally questionable nature of seeing human flesh as grass, that the chore needs such repetition suggests that its success is very limited. Moreover, the circumstances of those four campaigns have not been morally equivalent. Gaza's outside contact has been steadily constricted since the sealing of its borders in 2007.

The biggest difference, however, has been in the shifting nature of Hamas. When the Muslim Brotherhood took power in Egypt, it allowed Hamas to import arms from Libya and Sudan and cash from Qatar. Hamas was confident and assertive.

But when the Islamist-led government of Mohamed Morsi was ousted last year, all that was choked off by the Egyptian army which feared the links between Hamas and the Brotherhood. Egypt closed the tunnels through which Hamas fighters had travelled in the 2011 revolution to spring Brotherhood members from jail. Brotherhood supporters had used the same tunnels to escape to Gaza after Morsi's downfall.

The action by Egypt was so effective that, by the start of this year, Hamas was almost bankrupt. Worse still, it had lost the support of its long-time allies Syria, Iran and Hezbollah in Lebanon because Hamas chose to back the rebels fighting to unseat Assad.

So weakened was Hamas that it was forced into a deal with its oldest rival, the more moderate Palestinian Authority, led by Mahmoud Abbas, in the West Bank. Three months ago it even agreed to back a Palestinian unity government of technocrats – in which Hamas was allowed no members – which recognised Israel and renounced violence.

In the past, the Israelis complained that the Palestinians were so fragmented that no faction could deliver on any peace deal. Now Abbas had a controlling position. Washington and Brussels backed him. Everything was in place for a package to bring Gaza back under the control of Abbas, to disarm Hamas, to reopen crossing points to Egypt and Israel, monitored by EU observers, and to pour millions of dollars into Gaza's reconstruction as a precursor to a viable Palestinian state.

But instead of welcoming this sign of growing moderation, the Israeli Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, resorted to his old tactic of divide and rule. In June, three Israeli teenagers vanished in the West Bank. Netanyahu ordered a "hostage rescue operation", despite intelligence that the youths were already dead, which escalated into the onslaught against Hamas.

The eyes of the world have turned to Iraq, where Christians and Yazidis are on the run from fundamentalists. Out of the public gaze the mowing of the Gaza lawn continues. But these are not the tactics of a just war and they will not bring a lasting peace.

Paul Vallely is visiting professor of public ethics at the University of Chester

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks