Into the Minotaur’s cave of diplomacy: how Russia became Syria’s deterrent

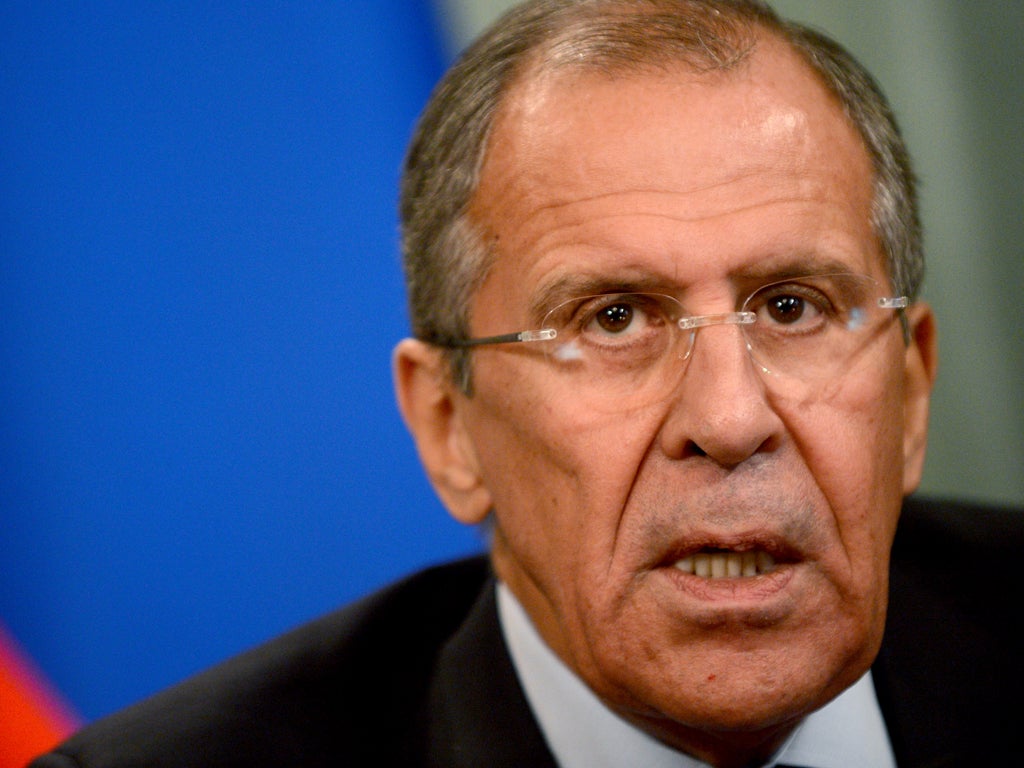

The Syrians, who often memorise poetry, like Lavrov: they believe he writes it in his spare time

The Syrian delegation to Moscow left Damascus on the night of Saturday 7 September, as much to find out its fate as to negotiate.

The US President Barack Obama and the Russian President Vladimir Putin had been hatching their plan to prevent American missile strikes and Walid Muallem, Syria’s extremely shrewd Foreign Minister, had no idea what it was. Far from bringing specific proposals to Russia, he wanted to know what the Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov knew – if he knew anything at all.

It was a weird situation. Syria did not want to be attacked by the US after sarin gas was used in Damascus on the night of 21 August, but it must have been clear that the Syrian regime – the principal target of American cruise missiles – had been cut out. Russia was making the decisions.

Muallem and his team – who are well-known in the Arab world and especially in Iran (and in the good old days, in London, Washington and Paris) – arrived at Sheremetyevo airport exhausted at dawn on Sunday 8 September, checking in, as they always did in Moscow, at the President beside the Moskva river, a cavernous and soulless hotel of the Brezhnev era. Their appointment with Lavrov was set for Monday at the Russian foreign ministry and Muallem and his delegation, still tired from their overnight flight, talked to Damascus and watched the satellite television shows out of Washington.

This was a moment in Syria’s history of which Muallem and his colleagues were all too aware. The foreign policy of Syria – or perhaps its military policy – was being decided by others. And so it came to pass that on 9 September, Muallem sat opposite Lavrov in the ministry. The Russian Foreign Minister bluntly told the Syrians what he thought. It was obvious from the start that he believed that Obama was going to strike their country.

This was not good news, especially when Lavrov made it clear that the operation would “definitely” take place. There was some discussion before Muallem stated his own country’s position: that “if the real reason for the proposed aggression against Syria was the chemicals, then diplomatic means have not been exhausted”. The Syrians like Lavrov – they believe (with what proof I have no idea) that he writes poetry in his spare time, something which would naturally appeal to a people who often learn Arabic poetry by heart before they can write. “He is a good friend to the Arabs,” is a constant refrain in Damascus. Readers must be left to decide if this is true.

Digging like a sleuth for the details of Russian-Syrian diplomacy – never mind the extraordinary military relationship – is like wandering the cave of the Minotaur. A wrong turning can put you in danger, a long-standing friend lost forever, a contact angered, an official enraged by an understanding lost in translation. So as your correspondent in Damascus tip-toes through Russian and Syrian sources, he must remember the risks. This is the best I can do and I have every reason to believe it is spot on. It is a story that tells you about the future Syrian state.

In any event, Lavrov broke off the conversation by telling Muallem that he was going at once to see President Putin at the Kremlin. “I will get back to you,” he peremptorily told the Syrians. Muallem again insisted that “diplomacy is not exhausted”. He must have hoped he was right; after all, if he was wrong, he might not have a Damascus airport to return to.

The Syrians returned to the bleak President hotel for lunch. In Washington, John Kerry was blathering on with more threats. Syria must hand over chemical weapons. They only had a week to hand over an inventory. At 5pm Lavrov called Muallem. They should meet in an hour. There was to be a press conference.

All along, Muallem had insisted that Syria wanted to sign the treaty banning chemical weapons. Yet everyone – not least the Russians – knew that Syria’s chemical arsenal was its only deep strategic defence if the country faced a doomsday war with Israel. Still Muallem did not know what was in store for him. He and his colleagues had not slept for 36 hours. Lavrov was worried for different reasons. If the Americans hit Syria, they would destroy Bashar al-Assad’s army, Islamists might storm into Damascus and Russian forces – with a naval base and marines in the Syrian port of Tartus and other warships at sea in the eastern Mediterranean – would be “forced to react”. This, at least, is the Russian version of events.

Now Lavrov told Muallem of Putin’s deal: all Syria’s chemical weapons to be monitored, details handed over within days, all stocks to be under international control within a year. And the Russians would be most grateful if Muallem – at a press conference that evening – would be good enough to agree. Muallem called Damascus. He talked to the government and of course to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. He agreed. And so a long-faced, exhausted Muallem appeared in front of the world’s television cameras – apparently almost overwhelmed with exhaustion – to “say yes” (in the words of the Russians).

Syria wanted to save its people from aggression and placed complete confidence in its Russian friends. One of his assistants, Bouthaina Shaaban – who is also an adviser to Assad – looked equally overwhelmed.

Afterwards, Muallem told Lavrov that the agreement took from Syria its “No 1” weapon. And Lavrov replied: “Your best weapon is us.”

And that was it. Syria’s strategic deterrent had become Moscow. Kremlin rules.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks