In the visual arts aesthetic standards can't be measured by hard labour or the lack of it

Plus: Could an Indonesian fisherman understand the 'The Waste Land'? And this journalist finds himself between a sock and an art place on the streets of Berlin

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.How hard do we want artists to work? I ask the question because I've recently encountered paintings which appear to be at the opposite ends of a spectrum of embedded effort. One group were conspicuously worked upon – and while the labour that went into them wasn't really their subject matter, I doubt that many viewers will not have thought something like, "How hard would it be do that?" The other group will have provoked a similar question – "How hard can it be to do that?" – but with a crucially different intonation. The first would be uttered in tones of mild awe, the second with a note of scepticism. And yet, for the sake of argument, I'm prepared to believe that the work that went into these different endeavours was pretty similar.

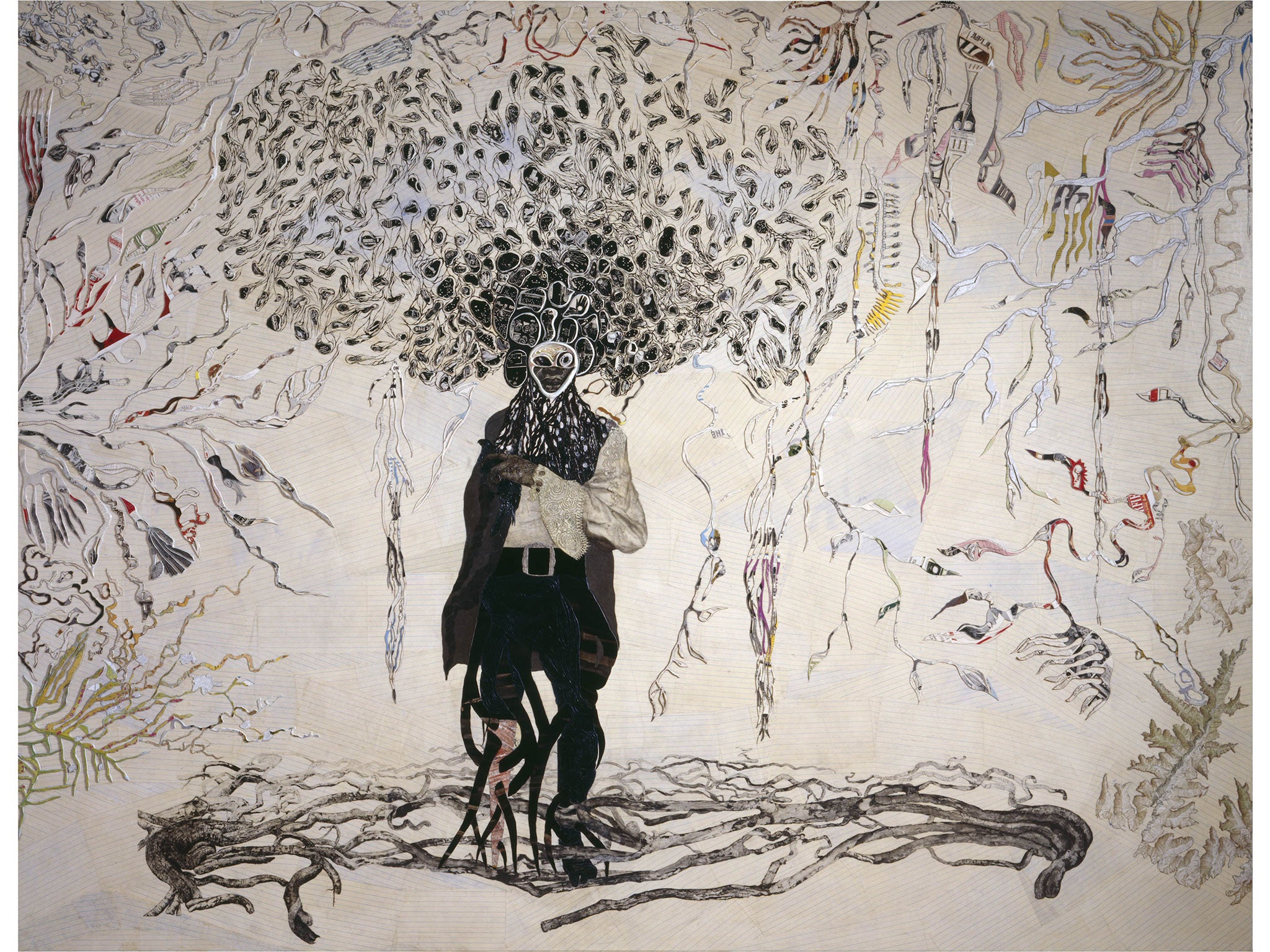

The labour-rich paintings and works were in Tate Modern's show AxME, a retrospective of the work of Ellen Gallagher and the labour-light ones were on show at the Saatchi Gallery's current survey show of young British artists New Order: British Art Today. And right away it needs acknowledging that the work of making a piece of art can't be reduced to what's done to the canvas or the piece of paper which preserves it. The fable about a Japanese artist spending days staring at a blank sheet before stepping forward to inscribe a single, flowing mark on its surface comes to mind. Did the work take days or just a few seconds? And how exactly do you account for everything that's gone into making the artist? Paintings can't be measured in kilojoules, with a straight read off of their stored energy.

Which doesn't stop us feeling that we're entitled to make judgements on the basis of the work we can see. You can't say how the judgement will go, either. It would be possible to look at Gallagher's densely layered images, collaged and constructed at a very fine grain, and feel that she didn't know when to stop. It wasn't my reaction – I found the intricacy beautiful in a lot of cases. But there is a kind of inherited suspicion of meticulous and laborious effects in contemporary art, particularly if it hasn't been made safe by delegating the grind to a studio assistant. "Trying too hard" might be one way of putting it: a sense that the artist hadn't sufficiently enfranchised his or herself from an urge to display mere skill.

The exact opposite seems to be what Nathan Cash Davidson is aiming for in his paintings in the Saatchi show, which include a painstakingly cack-handed portrait of Henry VIII, done (in the words of the gallery website) "in a style of semi-detached sarcasm". Sarcastic about what, you wonder? The idea of a Tudor monarch, garlanded with jewels? Or the idea of painting itself, with its embarrassing foregrounding of technical ability? It looks very much like the latter – and the rubric on another work confirms the suspicion: "Disregarding pictorial niceties (anatomical accuracy, compositional logic, tonal consistency) means Davidson's painting is invested with the immediacy of a story told by an excited child," it reads. And looks as if it was painted by one, you think, forced back on the hoariest reaction to new art. Conspicuous labour, by this account, comes to look like a kind of inauthenticity.

It's a hard prejudice to shift right now. As knowing consumers of art it seems we don't want the mixed media to include sweat, whether it's revealed by a hard-earned proficiency that would be inaccessible to the generality or by work that seems unperturbed by laborious repetition (the "every sequin sewn on by hand" effect which you get from some of Gallagher's work). But I have a feeling, too, that it is a prejudice that may fail quite suddenly, if only because it is historically so anomalous. And I wonder whether Davidson secretly longs to paint unsarcastically.

English is not the cruellest tongue

An interesting claim in Terry Eagleton's new book, How to Read Literature, when he's discussing TS Eliot's ambition to create an instinctive poetry. "An Indonesian fisherman could probably grasp the meaning of The Waste Land," writes Eagleton, "since he has intuitive knowledge of the great spiritual archetypes on which it draws". He goes on. "It might help if he was also able to read English, though perhaps it is not essential". I think his tongue is in his cheek. But it's hard to tell. I hope not. I cherish the idea of a young man on his proa, setting out from Surabaya, chanting: "Frisch weht der Wind/ Der Heimat zu,/ Mein Irisch Kind/ Wo weilest du?"

Between a sock and an art place

Walking down the street, in Berlin I passed a street pole which, like most street poles in cycling cities, had a bike locked to it. What was unusual was that this pole was covered up to about eight feet in a snugly fitting multi-coloured sock, knitted by some unknown hand. My instinct – corrupted by years of cultural journalism – was to assume that this was some kind of artistic intervention, perhaps "exploring" ideas about domesticity and the "living" space of the street. Then I stopped, because it seemed a pity to smirch the innocence of this object – its sprightly, purposeless oddity – with a neutralising explanation. Contemporary art is all very well. But sometimes you fear that it's done pure, batty eccentricity out of a job.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments