In defence of the humanities: Why this Government is wrong to scorn an arts education

Our next generation of artists and film-makers will suffer from these cuts

Back in 2005, David Cameron said something that made me consider, quite out of character, voting Conservative. “Education that inspires and instils a love of books, of knowledge and of learning,” he declared, “is one route to a happy and fulfilling life.” For someone invested in the arts, particularly in the role of humanities education in producing a thriving arts sector, that was quite an arresting sentiment.

But, eight years down the line, the Conservative-led coalition has pioneered an arts policy that, in the words of a recent article by Sir Nicholas Hytner and Nick Starr, “adds up to little more than a reduction in investment”. As if that were not enough, Maria Miller, the secretary of state responsible for culture, recently gave a speech suggesting that she sees culture as a cash cow whose survival will depend on the economic case that it can moo for its own viability.

In much subsequent debate about the relationship between culture and a thriving economy, an equally important relationship has been neglected: the one between the arts and education. Many voices have rightly been raised against the closure of libraries and cuts to the Arts Council budget. We also need to question what is going on in the field of humanities education, and how this will impact the arts sector.

Under the coalition government, humanities education in Britain has been ruthlessly downgraded and dismissed. Even as Michael Gove’s “EBacc” – a disjointed league table measure – encourages schools to ditch arts subjects, cuts to funding councils have meant that taught masters courses are longer publicly funded, and funding for research masters degrees and doctorates in the humanities will be slashed by about 47 per cent and 20 per cent respectively from 2013-14 .

The cuts that have been made to humanities education at postgraduate level deserve particular attention, precisely because the average member of the public with no interest in academia will probably not be that bothered about them. There is, however, an intrinsic though largely invisible link between humanities research and artistic production. Is it really possible to think that artistic achievements - unlike scientific advances, businesses built up from the ground or vocational skills - come out of nowhere?

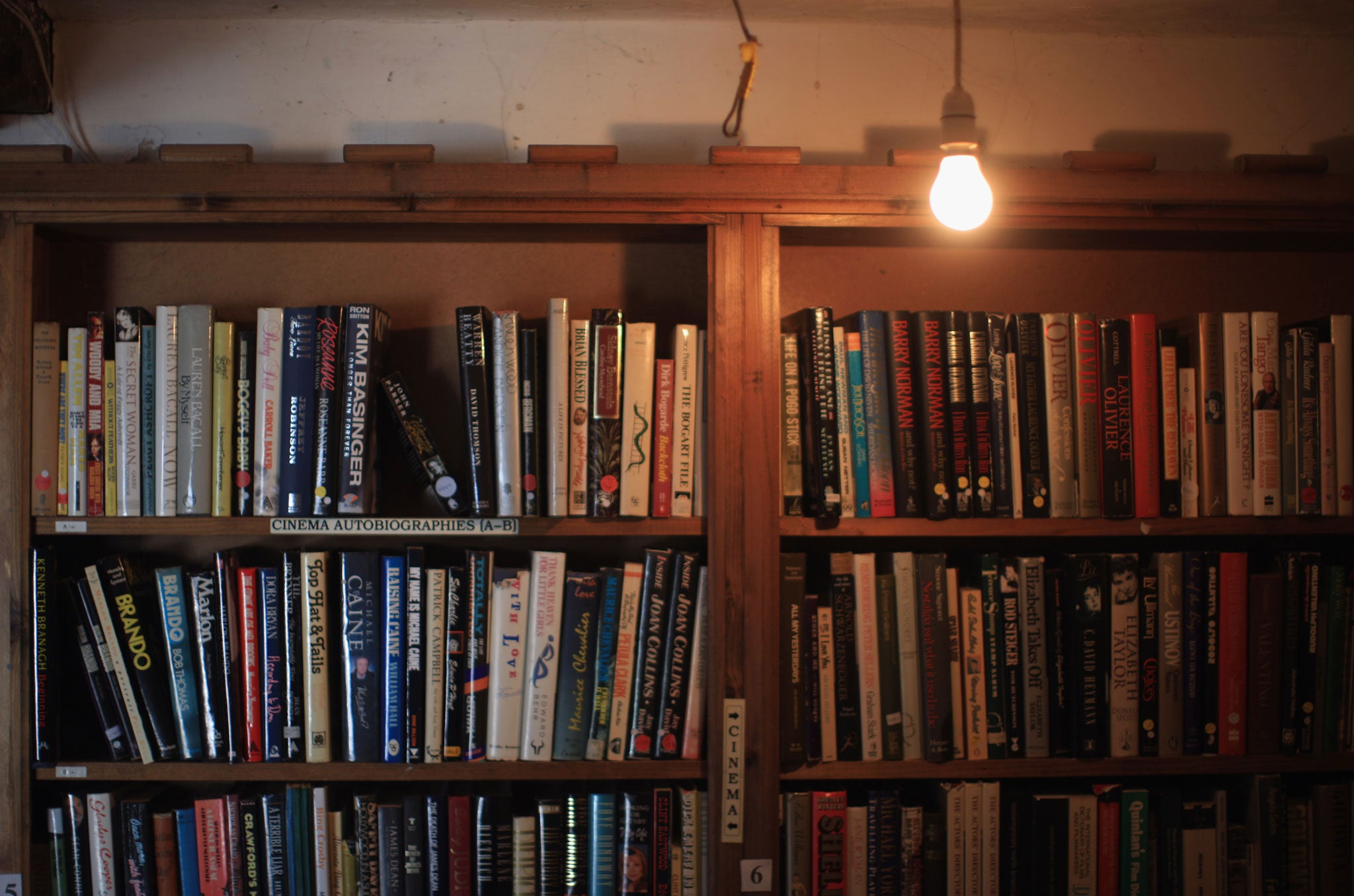

Underlying every book or film, each piece of music or drama or visual art, is the invisible weight of generations of humanities research. Art overlaps. Humanities research is seldom acknowledged, but is nonetheless an indispensable part of the development of ideas.

It is no coincidence that Iris Murdoch spent much of her writing life as a fellow in Philosophy at Oxford, and her novels were heavily influenced by Plato, Julian of Norwich and Simone Weil. It was integral to J.R.R. Tolkien’s fiction that he was a professor in Anglo-Saxon literature. Zadie Smith’s third novel, On Beauty, takes a humanities department as its setting, and its title is borrowed from the critic Elaine Scarry’s philosophical critique ‘On Beauty and Being Just’.

But the importance of research is not confined to writers with a foot in academia. Julian Barnes’s fascination with the literature of Flaubert, which has shaped his oeuvre in such important ways, derives partly from a special paper that he took as an undergraduate. Hilary Mantel’s magnificent record-busters are built upon a formidable body of historical research (she has cited cutting edge research on Henry VIII’s fertility troubles).

Literature doesn’t hold a monopoly on this phenomenon. Film-makers Ethan and Joel Cohen are majors from NYU film school and Princeton’s philosophy department. Steve Bell’s political cartoons are rooted deep in the artistic tradition of James Gillray. The music of Béla Bartók and Vaughan Williams was influenced by research into folksong; the music of Kraftwerk, which spawned electronica, was inspired by the composer Stockhaussen. Stewart Lee and Josie Long, among others, are humanities graduates who have emphasised the importance of their arts educations to their comedy. Numerous films, TV series and theatrical productions depend on the largely invisible but essential presence of historical consultants.

Even when a piece of art seems to come out of nowhere, it doesn’t. It can’t. Every single one of these artists encountered our canon either through a university degree or through independent research, understanding and absorbing it with the help of academics. They took their slice of our intellectual culture, passed it through their own creative filter, and put it out into the world for others to enjoy.

I know how this works because I’ve done it myself. I have published one novel, which was influenced by Barnes, Murdoch and Philip Pullman, and also drew heavily on narratological theory encountered during my undergraduate degree. I’m writing my second, which is influenced by the fiction of Hilary Mantel and Andrew Miller, but most heavily by the interdisciplinary environment of the Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies at the University of York.

Our current cultural scene is the work of diligent learners – many of them university graduates - whose learning was previously informed by the learning of others, sponsored by the state in a happier time to enrich our culture and ignite young minds.

But the Murdochs and Tolkiens and Lees and Coen Brothers of tomorrow are being forced to incur huge amounts of personal debt to qualify in their subjects. The academics whose work will buffer the art of tomorrow’s Barneses and Mantels are having their funding snatched away and being forced to compete for ever-dwindling pots of money to carry out their research.

David Cameron was right when he said in 2005 that learning is necessary for happiness. It fortifies our society like a subliminal layer of muscle and tendon. We seldom see it but by god, we will miss it when it’s gone.

As May 2015 creeps closer, as political parties start to construct manifestos, anybody who views a vibrant cultural, intellectual and emotional life as a desirable thing – for themselves, their friends and neighbours, their children – must struggle to articulate the value of humanities research, and to fight for it as a funding priority.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks