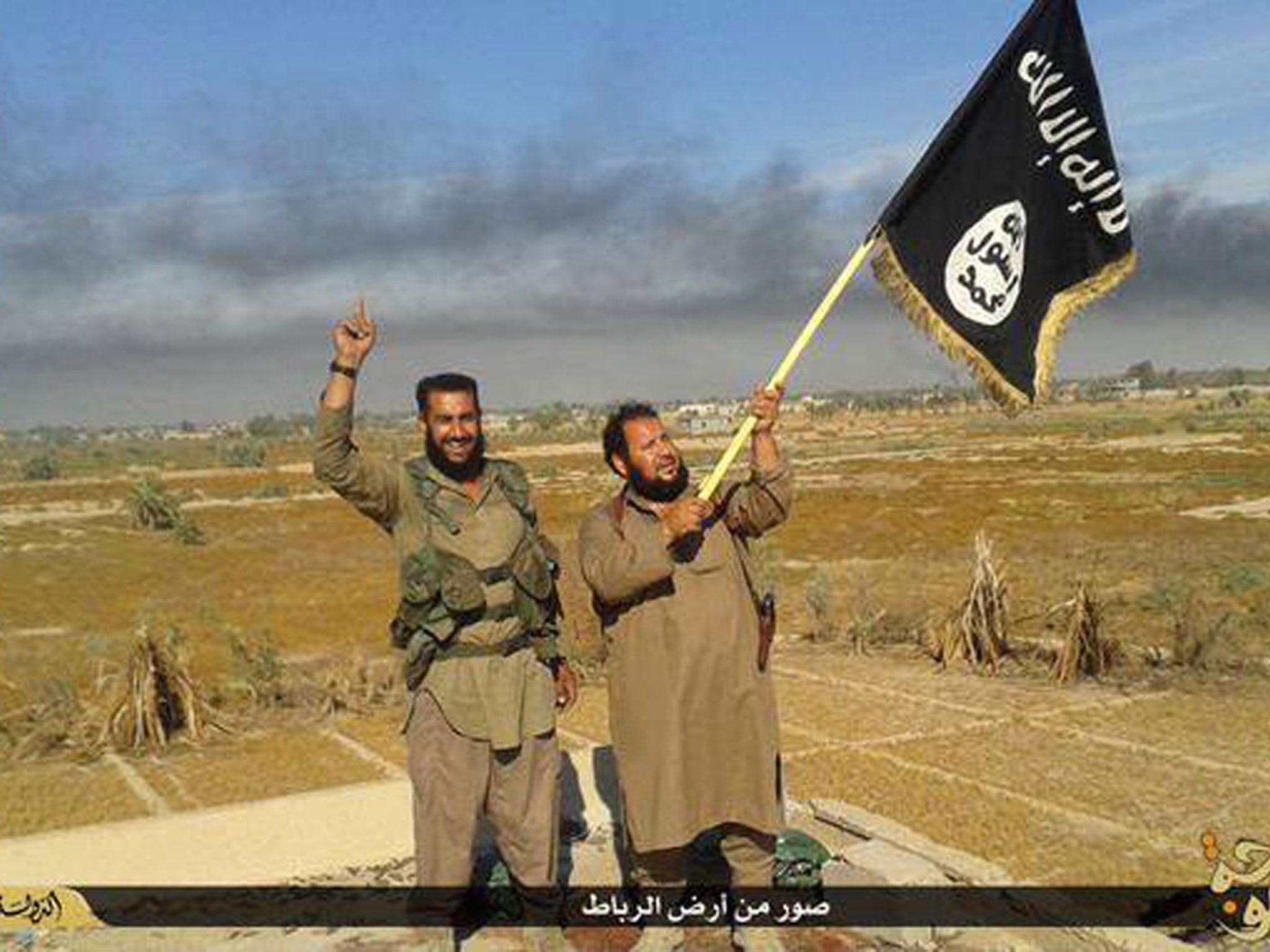

If the Government really wants to tackle extremism then it should recruit former Isis members

It may sound unpalatable, but working with those who have joined and then renounced the extremist group is working elsewhere

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Forget David Cameron’s five-year plan on terrorism, you know who would really be good at countering home-grown, violent Islamist extremism? Disgruntled British jihadists who have made the mistake of joining Islamic State and have lived to renounce their decision.

The thought of collaborating with people who have been involved with this grotesque, murderous group might not sound particularly palatable, but it is an approach that seems to have worked for the Danish government.

While we can’t empirically connect cause and effect, the Danish policy of rehabilitating jihadists who have come back from fighting with Isis in their so-called caliphate was followed by a significant cut in the number of people leaving the country to join the group. Denmark once had the highest European figures, relative to size, for citizens emigrating to fight with Isis. In 2013, 30 citizens made the journey to the Middle East; by 2014, it lost just one.

In the UK, returning jihadis face terrorism charges, though some 20 per cent of Britons who joined Isis are now trying to find a way to come home.

The model pioneered in the Danish city of Aarhus avoids criminalising such individuals unless there is evidence that actual crimes (rather than thought crime) have been committed. They bring former fighters back into the Muslim community, so that they are then able to share their devastating stories and help deter other potential fighters from leaving to join Isis.

This “soft-hands” approach coordinates between police, parents, social workers and welfare services. Returning jihadis are counselled, offered medical treatment or mentoring and given a way back into society. This policy comprises a preventative component too, so that people who are intent on joining Isis can be persuaded not to travel.

You would think the British government would take a look at such an obviously successful approach – but David Cameron’s government seems actively to be engaged in feeding extremism, rather than credibly trying to tackle it. The Prime Minister’s proposals to counter “Islamist extremism” are exactly the sort of unhelpful, marginalising methods that will be used by violent jihadists as fuel to power their latest recruitment drive.

However much Cameron talks about unity and collectivism, he also spouts the alienating, self-defeating claim that even Muslims that denounce Isis are in some way feeding extremism by not speaking up, or somehow turning a blind eye, or by talking about British foreign policy. It is as though any Muslim who cares about the Palestinian cause is one sermon away from becoming a throat-cutting jihadi.

If people – Muslims, those of other faiths, and those of none – cannot talk about foreign policy as being one element of the potential lure of Isis, the conversation is pushed underground. This is how violent extremists prey on secrecy, honing in on already vulnerable and disenfranchised individuals in a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Far from tacitly supporting violent extremism, community workers in Britain are asking the government for help, but their recommendations are simply ignored.

Extremism is not solely a “Muslim community” issue. Just take a look at those foreign fighters with the group that calls itself Islamic State: they are social media savvy and use cinematic styling in their video missives; they boast stockpiles of Nutella. These young radicals are not the creation of a particular community, so much as a part of our society at a whole.

This is what “home-grown” really means; grown by us – and the sooner we face up to this terrible reality, the easier it will be to beat it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments