If the economy really is picking up, the challenge is to use growth wisely

How long will this cyclical uplift last? Three years? Five years? Seven years?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The economic narrative has changed, and this week is as good as any to mark that transformation. Since the recession struck in 2008 most of the economic stories in the media have been about the sluggish nature of the recovery and the threat of another recession. As recently as spring this year there was a scare story, repeated in sombre tones, of a “triple dip” in the economy. This was not just the fault of the media, for even the International Monetary Fund warned that the Chancellor was “playing with fire” with the fiscal consolidation programme.

All that is gone. The current stories are quite different. They are about the nature of the recovery. So this week we have had rising concern about the surge in house prices. This paper’s front-page headline yesterday caught it well: “More evidence of a property boom (and why it’s a bad news story)”.

House prices are now climbing at their fastest rate since 2002. But we also had a fall in consumer inflation revealed yesterday, so as yet the recovery in asset prices is not yet feeding through into current inflation. We will have the Bank of England’s latest Inflation Report published today, which will upgrade the growth forecasts for both this year and next. We will also have strong employment figures, and let’s hope a further sign that this is bringing the level of unemployment down.

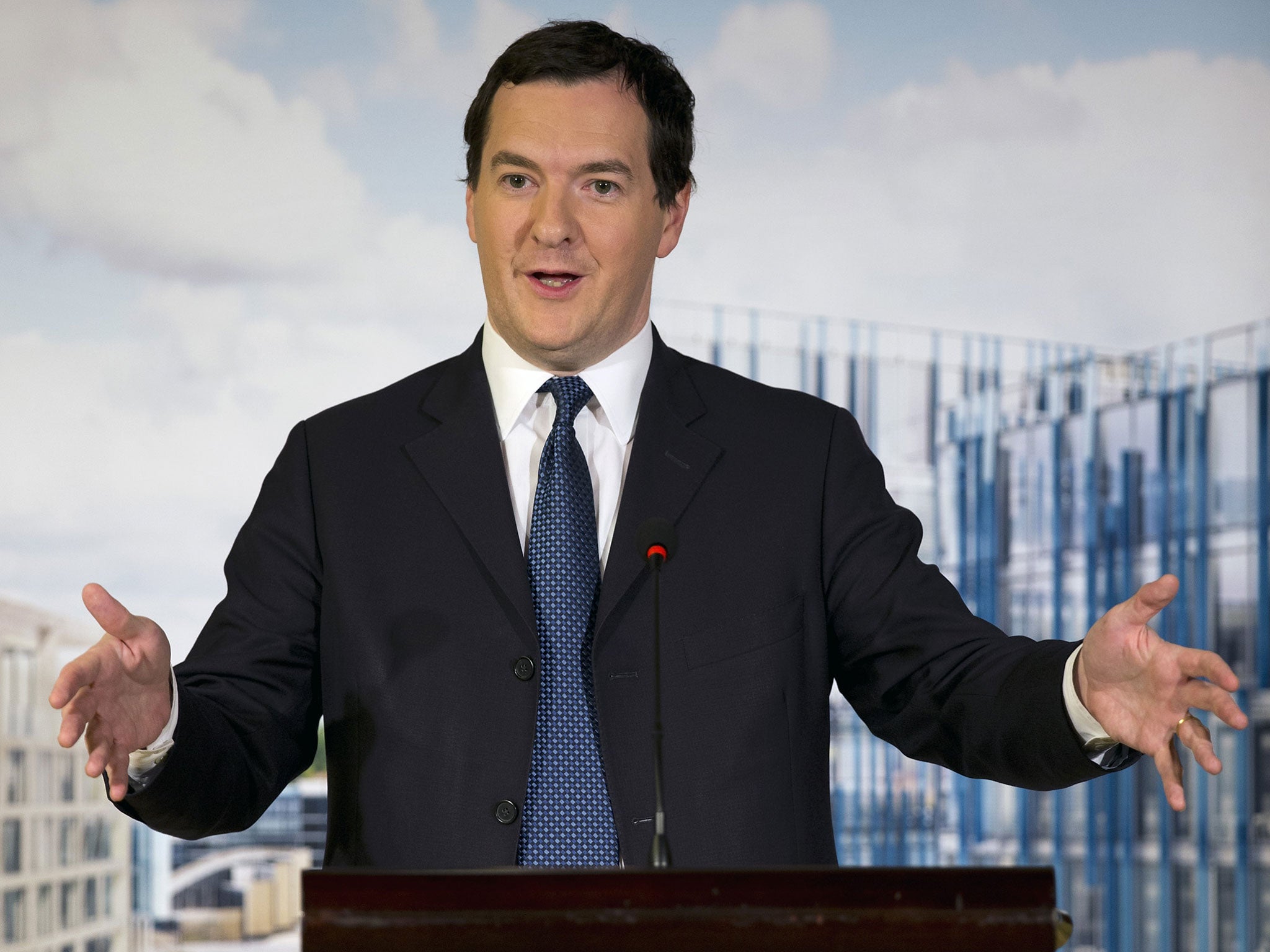

Seen through the prism of British politics, this is all encouraging for the Coalition, and maybe a bit awkward for the opposition, which made a huge thing about the failure of the Government to keep growth going again. Next month George Osborne will doubtless use his Autumn Statement for a bit of self-congratulation about how things have turned up, a prospect I find almost as dispiriting as listening to Gordon Brown telling us how he had eliminated boom and bust.

But to see things in political terms is to miss the big story. That story is that we almost certainly entering a period of solid growth and the issue is how to use it wisely.

That leads down a series of different paths. One question I find perplexing is how long this cyclical uplift will last: three years, five years, seven years? We cannot know, but it is of absolutely crucial importance. If it is only three years, we will still have a sizable fiscal deficit as we head back to recession. If it is seven, we have time to get ourselves into decent shape to withstand the downturn.

Another issue is how to wean ourselves off quantitative easing and near-zero interest rates. There is no obvious template for policy because these exceptional monetary measures have never been used before in peacetime. The downside, however, is starting to become evident, with the boom in house prices just one element of that. We have to do something about supporting savings. Interest rates below the level of inflation are a social disaster, for they punish the prudent and reward the speculators.

Still another strand is using growth to reduce inequality. There are two broad approaches here, one of which is for the state to act to reduce it directly by various tax and spending measures, the other to try to prevent inequality increasing in the first place. It is interesting that the Labour leadership is now focusing on the second line of attack, having followed under Gordon Brown an extreme version of the tax’n’spend model – the largest increase in public spending ever to have occurred in peacetime.

But as with the other aspects of the new narrative, this is not just a British concern, nor is it a rich/poor matter. It is also a young/old issue. To generalise, the young have tended to suffer more from the downturn than the old. That has happened in the UK, but particularly so on the Continent. The European social model does protect those already in employment, but at the expense of those seeking to enter the labour force. As even the laggards of the eurozone start to grow again, this insider/outsider issue needs to be tackled.

There is also a regional issue: to what extent will recovery spread and why are some regions left behind?

Finally, we are going to hear a lot more about the capacity of the state to get things done. One of the effects of the squeeze on public spending here has been to force much more productivity out of the public sector. There is some evidence that the quality of service has actually improved and there is certainly much more scrutiny of how decisions are taken and how outcomes might be better.

None of this is easy. But accepting that the recovery will be finite, we have to use the time wisely must lead to a different and more positive way of thinking about economics than we have had to endure over the past four years. A welcome shift indeed.

The truth about what young people see

A study from Ohio State University looked at 945 American films between 1950 and 2012. As you might expect, there has been a rise in gun violence, with gun use having doubled over this period. But surprisingly, it is higher now in PG-13 movies than in R-rated ones. As a result, young people are considerably more exposed to gun use than they were a generation ago, suggesting “that the presence of weapons in films might amplify the effect of violent films on aggression”.

The study notes that in July last year James Holmes killed 17 people in cinema in Aurora, Colorado, having left the screening of the Batman movie ‘The Dark Knight Rises’ and returned heavily armed. He identified himself to police as “The Joker”. The film industry has long tried to deny that there might be a link and many actors have publicly supported gun control. But if you want some fun just google “Hollywood actors and gun control” and you will see an awful lot of hardware.

Well done, London

London has more high-skill jobs than any other city in the world, reports Deloitte. The consultants looked at 22 job sectors, including finance, the law, media, software and education, and found there were 1.5 million people in those sectors, compared with 1.2 million in New York, 784,000 in Los Angeles, 630,000 in Hong Kong and 425,000 in Boston. Londoners regard it as normal that there are a lot of smart people at work in the capital. But if you looked from anywhere outside the UK, is it not rather a stunning achievement?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments