How the Blair government decided against adopting the euro

A special seminar of the Blair Years course was held at the Treasury last night with the civil servant and the special adviser who worked on the 2003 decision on the euro

The ninth seminar of the Blair Years MA course that I co-teach with Jon Davis at King's College, London, was held at the Treasury last night, because the special guest was Sir Dave Ramsden, the Treasury's Chief Economic Adviser. He was talking about the decision on the euro in 2003, for which he was the lead official, and his respondent was Ed Balls, his predecessor as Chief Economic Adviser at the time. They are now both visiting professors at King's.

Professor Balls was on mischievous form, asking Professor Ramsden before they began: "Which version of history are we giving them – the official version, the unofficial version or the really unofficial version?" He had spoken to the class early in the term and warned Ramsden that "they are quite theoretical, this group, so we should start with the Mundell-Fleming theory and then go on to the symmetry of stochastic variance".

Ramsden ignored him with good humour and talked instead about the "asymmetry in the volume of Treasury and Number 10 accounts" of the Blair government. He said Robert Peston's Brown's Britain was almost the only book telling the story from the Treasury point of view. He said he hadn't spoken to Peston, but that it was accurate.

He recalled that he had met Tony Blair in 1998 when he accompanied Gordon Brown as – "for one weekend only" – he was his speechwriter at a summit in Brussels. Brown gave quite an "amazingly pro-European" speech, he said, all about how the European Community had risen out of the ashes of the Second World War. "I didn't see Tony Blair again until the euro decision in 2003."

By that time, he learned from Peston's book, he had acquired a nickname. He was known as "the man in the white coat", portrayed as a "mad professor".

The euro decision was "for some people the high point and for others the nadir of Treasury control", he said. It was a "classic technocratic civil service exercise", putting both sides of the argument so that policy-makers could decide.

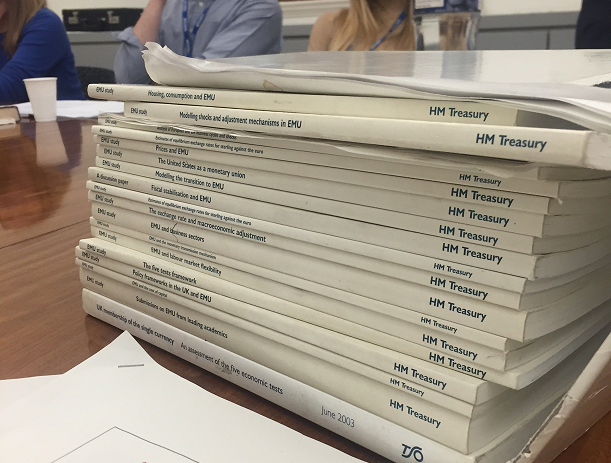

After the 2001 election the Treasury started what it carefully called "preliminary and technical work", so that it could minimise speculation by saying that it hadn't yet started the "assessment" of whether the UK had passed the five tests. "We had such fun filling out what we meant by those phrases," said Ramsden. Eventually there were 18 "preliminary" documents plus the "assessment" itself.

In early 2003 Treasury officials went to Number 10 for a series of seminars on each of the tests with Blair and Brown. "At the end of these seminars Tony Blair would say, that's very good, but is it yes or no?" But it wasn't until 1 April, All Fools' Day, that "Gus O'Donnell [Treasury Permanent Secretary], Ed Balls and I signed off on the key paragraph, which said joining the euro would not be in the national economic interest." When it was presented to the Prime Minister, "there was just a kind of silence – it was a challenging moment. Then Blair said, 'That's all very interesting, but I don't accept your conclusions.'"

It became obvious that the decision could not be announced, as planned, in the Budget on 9 April 2003. A slightly more positive version of the assessment, coming to the same conclusion, was eventually published in June 2009. "It was a momentous decision, taken in the old-fashioned way, in which the civil service prepared and ultimately persuaded both the Chancellor and in particular the Prime Minister that it wasn't right to join." The exercise was "the absolute highlight of my career as a more junior civil servant", he said. "As time goes by the assessment was borne out by subsequent events. A huge amount of work was put into policy not changing."

Ed Balls agreed. "You could read the tests now, 13 years on, and they stand the test of time."

Ramsden said that the Treasury "wasn't then so focused on economic history" – something Sir Nick Macpherson, the Permanent Secretary, has worked on and one of the reasons for the partnership with King's. Balls explained that one of his roles at the time had been to give the Treasury a historical view: "There have been frequent occasions in the past when a political consensus has formed on an economic question and it has turned out to be a catastrophe." The attempt to maintain the Gold Standard, repeated devaluation crises and the decision to join the exchange rate mechanism. "Putting politics before economics could destroy you."

He said that Blair and Brown "were united in their pro-Europeanism" but that Brown had become more cautious about the economic case, while "people around Tony Blair" were pushing hard for Britain to join. "I don't include Tony Blair among the people around Tony Blair who really wanted to join. I think he was satisfied with the outcome."

Ramsden agreed. Picking up one of the 18 volumes, Modelling Shocks and Adjustment Mechanisms in EMU, he said:

This is the paper that everyone who did join the euro should have read. When they had the euro crisis, it played out, as in Ireland: cheap credit, inflation, housing boom. We mapped it out and said it will happen to un-converging countries. Countries such as Ireland and Spain never had access to that kind of thing. The only country that did was Sweden [which voted not the join the euro in a referendum in September 2003].

To be fair to Tony Blair, this is when he really came to life. I did the analysis and Gordon Brown came in saying, Do you realise what this will mean for our labour market? Blair got this. He wasn't passive in all this.

In questions, Balls was asked about Sir Nick Macpherson's view that, if Britain had joined the euro, it would have "blown up" the currency. "We would have had a boom and bust. We weren't confident enough to say at the time that it would have blown up the euro, but looking back it is clear that it would have done."

Asked if he could imagine the UK joining in the next 30 years, Balls said:

I used to say it won't happen in my political lifetime – I've had to drop the 'political'. It won't happen in my lifetime. Can you imagine a cross-party consensus that it was the right thing to do? We are a long way from there being a consensus, on really good grounds.

He was asked about Roy Jenkins's idea – advocated by Peter Mandelson in the previous class – of holding a referendum in 2000-01 on the principle of joining and then taking the decision later:

We were worried that once you had taken the decision in principle it would lead to a decision made for political reasons. I have a lot of respect for Roy Jenkins but he was absolutely wrong and completely out of touch with the British people.

Asked what might have happened if there had been no 9/11, which came on the day Blair intended to make his most pro-euro speech yet to the TUC, Balls warmed to his theme:

I don't think Tony Blair really wanted to join. He didn't think it [the referendum] could be won. He actually understood the economics. His credibility in the European Council depended on being a good European, and that depended on saying you wanted to join the euro. He had the Foreign Office breathing down his neck, but most of the time Tony Blair and Gordon Brown were on the same page.

Before the 2001 election Tony Blair met Paul Keating [former treasurer and prime minister of Australia]. He told Gordon and me that one of the things Keating had said was, "Whatever you do, don't join the effing euro." Why would he tell us that? He didn't say it as if he disapproved of it; he said it as if he was thinking, "Smart guy."

Jon Davis and I are grateful to Sir Nick Macpherson, outgoing Permanent Secretary (and another visiting professor at King's, who dropped in for part of the session) for allowing us to hold the class at the Treasury.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks