House prices are booming again but the bust that’s bound to follow will cost us dear

A rise in rates would inevitably cause an immediate and deep house price crash

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I was in the beautiful city of Charleston, South Carolina where the first shot was fired in the American Civil War over the weekend for the wedding of my second daughter. Two down, none to go.

As the bills rolled in by the fistful – including for a horse-drawn carriage so I could get her to the church on time – it set me thinking about wealth or lack of it, not least because I have been reading a really important new book on wealth in the UK.

The newly knighted John Hills and five co-authors from the London School of Economics have just published an authoritative study on the distribution of UK wealth, and how it changed up to the point when the Coalition took office. They illustrate the enormous importance of housing wealth in the UK and how house price rises lowered wealth inequality.

They use the most comprehensive survey ever carried out on wealth in Britain – barring perhaps the Domesday Book – the Office for National Statistics’ Wealth and Assets Survey, which puts a value of £5.5trn on the total value of personal wealth, the survey having been carried out between 2008 and 2010.

This was nearly four times annual national income at the time. Adding in the value of people’s rights to pensions from employers and other private sources, generally of most importance to people higher up the wealth distribution, the total was even higher, £10trn. If rights to state pensions were included, the number would be higher still.

Of that total, £3.4trn was accounted for by the value of houses and other property, net of mortgages, £1.1trn by net financial assets and £1trn by what the ONS counts as ‘physical wealth’, which includes consumer durables, the contents of people’s homes, and vehicles. It even includes £1.8bn for the value people put on their personalised vehicle number plates.

Wealth inequalities in Britain are much greater than those we are used to seeing when looking at income differences. For instance, those at the 90th percentile of the earnings and income distributions have weekly earnings before tax or household incomes after tax that are around four times higher than those of people near the bottom at the 10th percentile.

For household wealth, the corresponding ratio is 77 to one. Absolute gaps in wealth holdings have grown rapidly in recent years, reaching a position in 2008–10 where a tenth of households had net assets of more than £970,000, more than 75 times the cut-off for the least wealthy tenth, but a tenth had less than £13,000. Hills et al found that the top 1 per cent or 240,000 households had aggregate total wealth of around £270bn in 2008–10.

Interestingly, between 1995 and 2005, wealth inequality narrowed because of the rise in house prices – if they hadn’t risen, according to Hills et al, wealth inequality would have been largely unchanged. Those of course with little or no wealth were left behind while those with mortgages, those in middle age and those who were most highly qualified gained most from house price increases.

To put this in context, according to the Halifax house price index, average prices rose by an average of 16 per cent a year between January 1995 and January 2005. Between January 2005 and August 2007, they grew by a further 21.8 per cent, which is likely to have narrowed wealth inequality even further. But then prices started to tumble as the Great Recession took hold. By the end of 2012, average house prices were around 20 per cent below their peak.

But the downward trend in the UK has stopped: house prices in 2013 have started to rise again. Between January and July 2013 they rose 4.2 per cent.

This does not look sustainable in the long run, given that the main determinants of house prices are wages, which aren’t growing, and interest rates, which are at historic lows and eventually must rise. A rise in rates any time soon, as proposed irresponsibly by Ros Altmann and Andrew Sentance, would inevitably cause an immediate and deep house price crash.

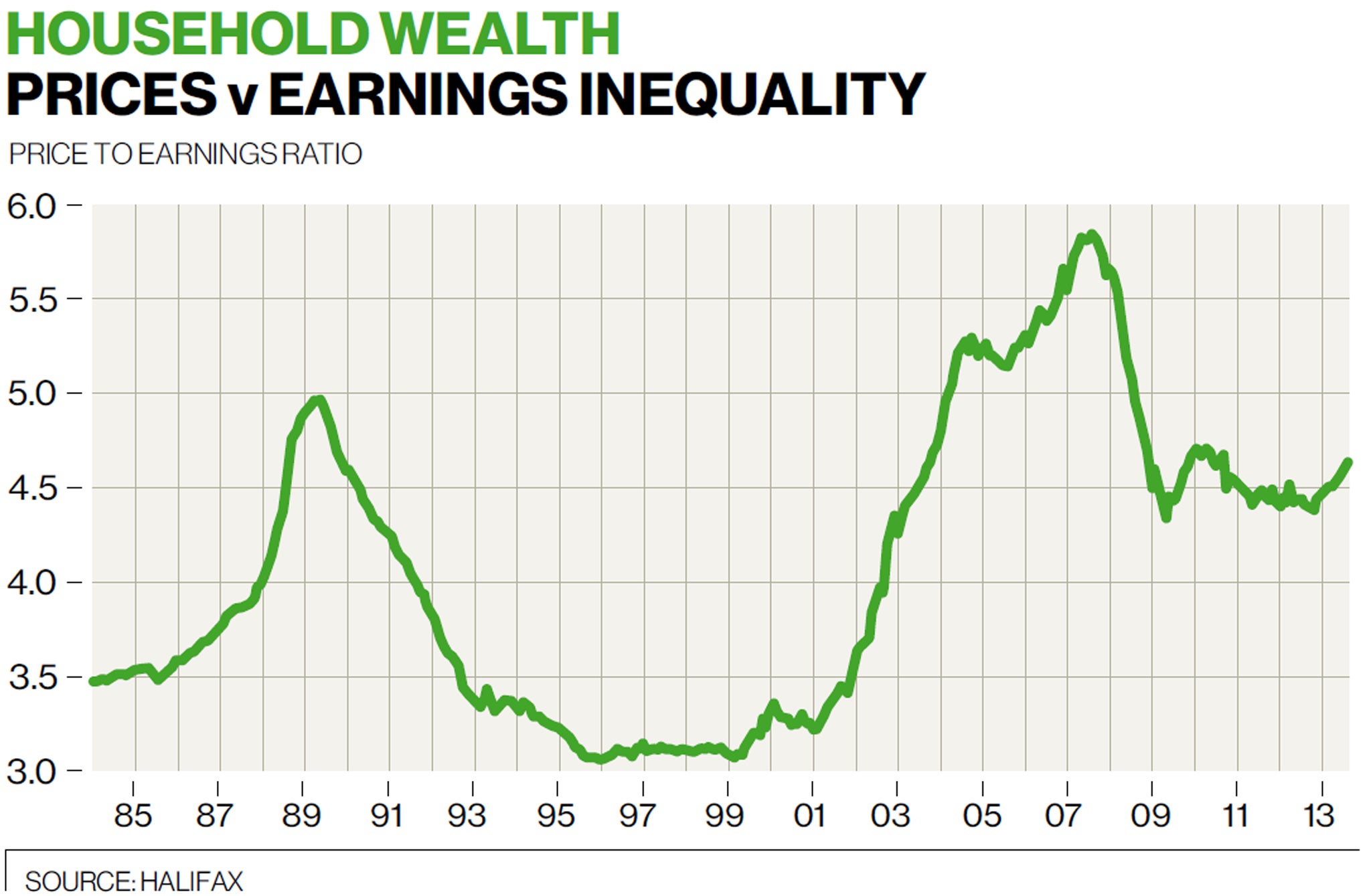

Earnings of full-time men rose by an average of 6.1 per cent between January 1995 and January 2005, well below the increase in house prices. The chart shows that the house price-to-earnings ratio rose to 5.8 in April 2007 from 4.8 only four years earlier. By October 2012, the ratio had fallen to 4.39 but has risen since then to 4.62.

What goes up must come down again, given that equilibrium of around 3.65 or so looks sustainable in the long run. Bank managers historically don’t grant mortgages of more than four times earnings. This suggests house prices are currently as much as 25 per cent overvalued. When house prices fall, they usually overshoot, suggesting falls may be even greater when rates eventually rise.

Slasher Osborne’s irresponsible new Help to Raise House Prices Scheme seems to be driving these increases. Homeowners have started spending as they see the value of their homes rise. So the solution to a housing boom and bust is to start another boom that will inevitably bust.

It is hard to find a single economist who thinks it is a sensible idea – it is cynically designed to buy votes. Based on the Government’s historic defeat over Syria, it is likely to need every vote it can get in 2015. The inevitable fall in house prices that is coming will cost the country dear, as Mr Osborne has provided a £100bn backstop. Here we go again.

Wealth in the UK. Distribution, Accumulation, and Policy by John Hills, Francesca Bastagli, Frank Cowell, Howard Glennerster, Eleni Karagiannaki and Abigail McKnight, Oxford University Press, 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments