Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Without wanting to sound like a candidate for Private Eye's Pseuds Corner column, it was Hermann Hesse who first identified the supreme importance of comedy as a key to understanding the human psyche. "How people love to laugh!" the author of The Glass Bead Game once remarked. "They flock from the suburbs in the bitter cold, they stand in line, pay money and stay out until past midnight, only in order to laugh awhile."

If the modern humour-fancier is more likely to acquire his or her levity from television or the internet, then the soundness of Hesse's point remains, and a social historian seeking to pronounce on aspects of national identity will always find the way made easier if he or she begins by considering the question of what that nation thinks funny.

Or, to differentiate even further, what the individual parts of that nation consider themselves amused by. One of the most fascinating conclusions of "State of Play: Comedy UK", last week's report on attitudes towards British humour, was the emergence of profound regional variations. According to the compilers, all parts of the country now find sexual jokes acceptable, with the single – and, it must be said, singular – exception of Yorkshire, where sex jokes rated -5 on the humour index. On the other side of the coin, comedy audiences in the South-west apparently fall over themselves to giggle at smut, with gags "of a lewd nature" gaining a +33 score, while London and Wales are supposedly the next biggest market for Roy "Chubby" Brown's rib-ticklers about his helmet.

Already, some of the traditional analyses of reactions to risqué humour are beginning to look very out of date. Historians of comedy, for example, always used to maintain that sex jokes went down badly in the West Country because of its pious non-conformist heritage, but no, here are the proud descendants of all those Devonian puritans screeching over misplaced cucumbers and the lift attendant who was so keen on going down. On the other hand, I was interested to find that the Scots are believed to find lavatory humour less amusing than other parts of the UK, while – inevitably – relishing quips about the hapless English, and that audiences in London and the East Midlands are, mysteriously, more likely to welcome political jokes.

Your first response to this harvest of ripe sociological data is to assume that the results must be entirely arbitrary, that certain people in the sample find certain things funny for reasons so psychologically complex or diffuse that no wider conclusions can be reached. In fact, several broader generalisations instantly present themselves.

The first, naturally, is that audiences have become a great deal more tolerant than they were in the days when Max Miller could face censure from the BBC for observing that, when asked by a girl on a crowded Piccadilly Line tube train "Is this Cockfosters?", he replied "No, Smith's the name." But the second – miraculously in a standardised age, where the same entertainment is endlessly transmitted into all front rooms – is that many of the old regional separations of British humour endure.

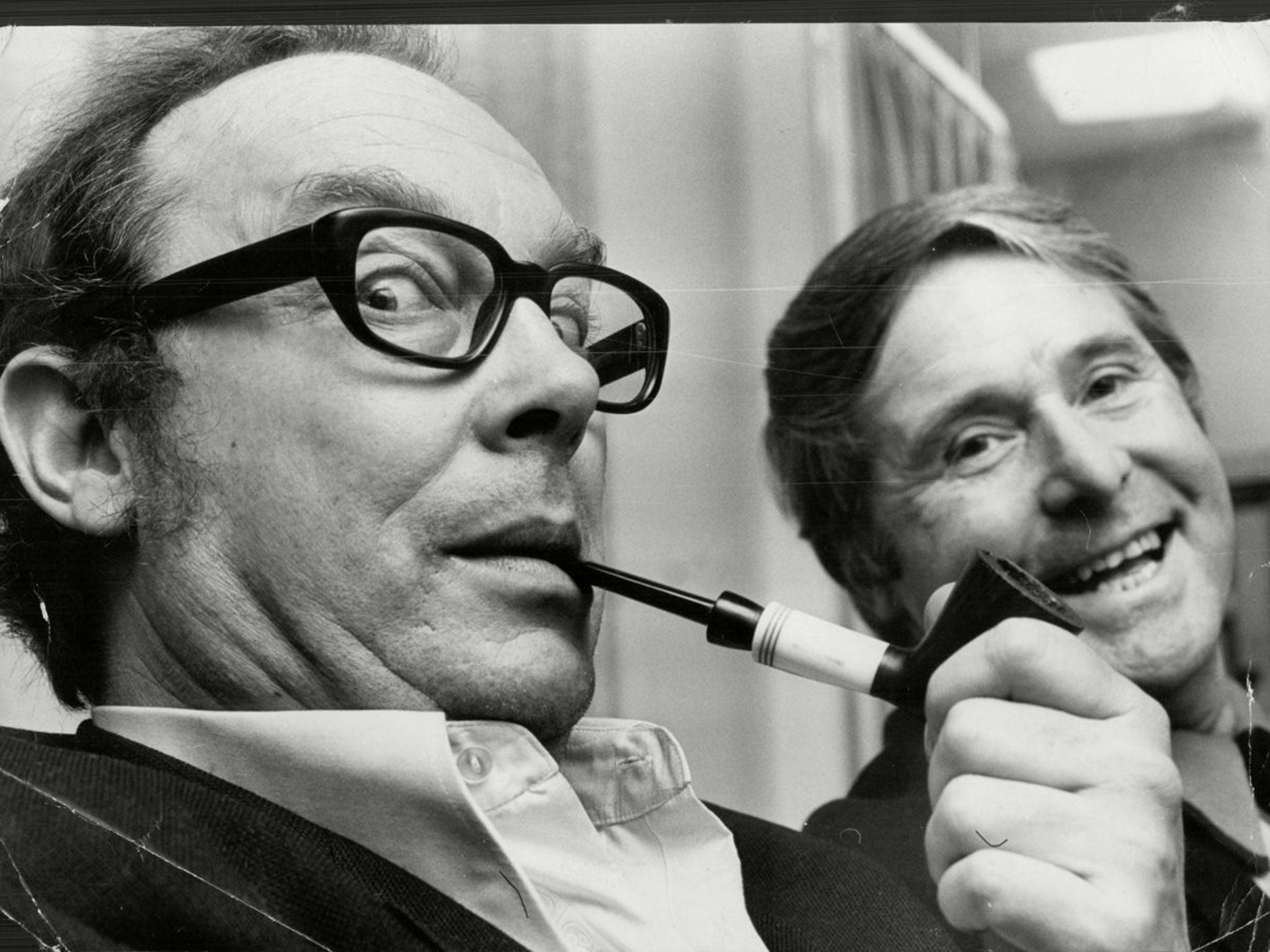

And what exactly were these? Well, Scotland, understandably, has always been a law unto itself where comedy is concerned. The English comedian who marched on a variety-hall stage in Dundee in the 1930s and told a joke about clergymen was likely to be booed off out of respect for "the minister", and even Morecambe and Wise, paying their third visit to the Glasgow Empire in the early 1950s, were received in complete silence, after which the stage doorhand is supposed to have remarked "Aye lads, they're beginning to like you."

Yorkshire audiences, too, were suspicious of quick-talking southern patter-merchants and preferred comedians who told jokes against themselves rather than making others their victims, with a preference for gormless no-hopers who wandered on stage to complain about their want of luck with women or lamented the difficulties of "courting".

At the heart of these divides lay, if not the glimmerings of regional identity, then an awareness of the characteristics which separated, or were thought to separate, the various parts of the UK. The non-Yorkshireman might have been unreasonably amused by jokes about northern stinginess, bluffness or self-assurance (as my father observed of his time in the RAF, there was never any danger of not knowing what to do as the people from Yorkshire knew everything, and what they didn't know the people from Lancashire did), but the Yorkshire variety-hall audience wanted to be reassured of its communality, its solidarity, its detachment from the brash, fault-finding individualism of the world beneath the Trent.

If the part of Britain was geographically out on a limb, then its humour became yet more isolationist, yet more concerned to establish difference and the sense of its own priorities. One of my favourite Norfolk jokes, for instance – which may even have made it to Punch in the mid-1960s – finds a couple of cloth-capped ancients seated by a village green and offering directions to a tourist. "I expect you gentlemen have lived here a very long time," the tourist suggests. "That's right sir," the elder of the two responds. "I've been here since afore the railways come, but e's only been here since Beeching took 'em away" – a characteristic combination of rootedness (we Norfolk people have been here a very long time), one-up-manship (I am better than my friend) and profound contempt for a metropolitan bureaucracy prone to interfer in ordinary people's lives.

When, in addition, the joke incorporates dialect it turns into a kind of spiritual drawbridge, that can only be raised by listeners who have done their homework, are on the teller's side rather than ranged against him. Take, for example, the traditional Norfolk dialogue exchange "Ha' your fa' got a dicker, bor?" (translation: "Does your father own a donkey my friend?") "Yis, and he want a fule ter ride him. Can yer come?" – quite as exclusive in its way as Max Boyce bouncing on stage with an outsize leek or the late Tommy Morgan performing with a Scottish accent so thick that a BBC producer keen to bring him to television seriously considered the use of sub-titles.

Naturally, the wider significance of these comic shadings cannot be over-stressed, for taken together they amount to a gigantic raspberry blown in the face of all those homogenising cultural influences we hear so much about these days. The only drawback to "State of Play", in fact, is that it doesn't head out east and west to consider national, as well as regional, differences. One of the advantages of British humour, after all, is that it is nothing like American humour, the former (mostly) relying on character and irony, the latter still largely based on the wisecrack and encouraging spectators to hoot like dervishes at the sound of minor point-scoring. Whether or not you find the spectacle of the fat man in Cheers proclaiming "Boy walks into bar. Boy drinks beer. Boy has another beer" while the audience goes into fits amusing or not, all this is vitally important.

Just as a book that everybody liked would almost certainly turn out to be unreadable, so a joke that everybody found funny would suggest that the society that had produced it was scarcely worth living in.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments