Errors & Omissions: When is a book a tome?

Our Letters Editor reviews the slips from this week's paper

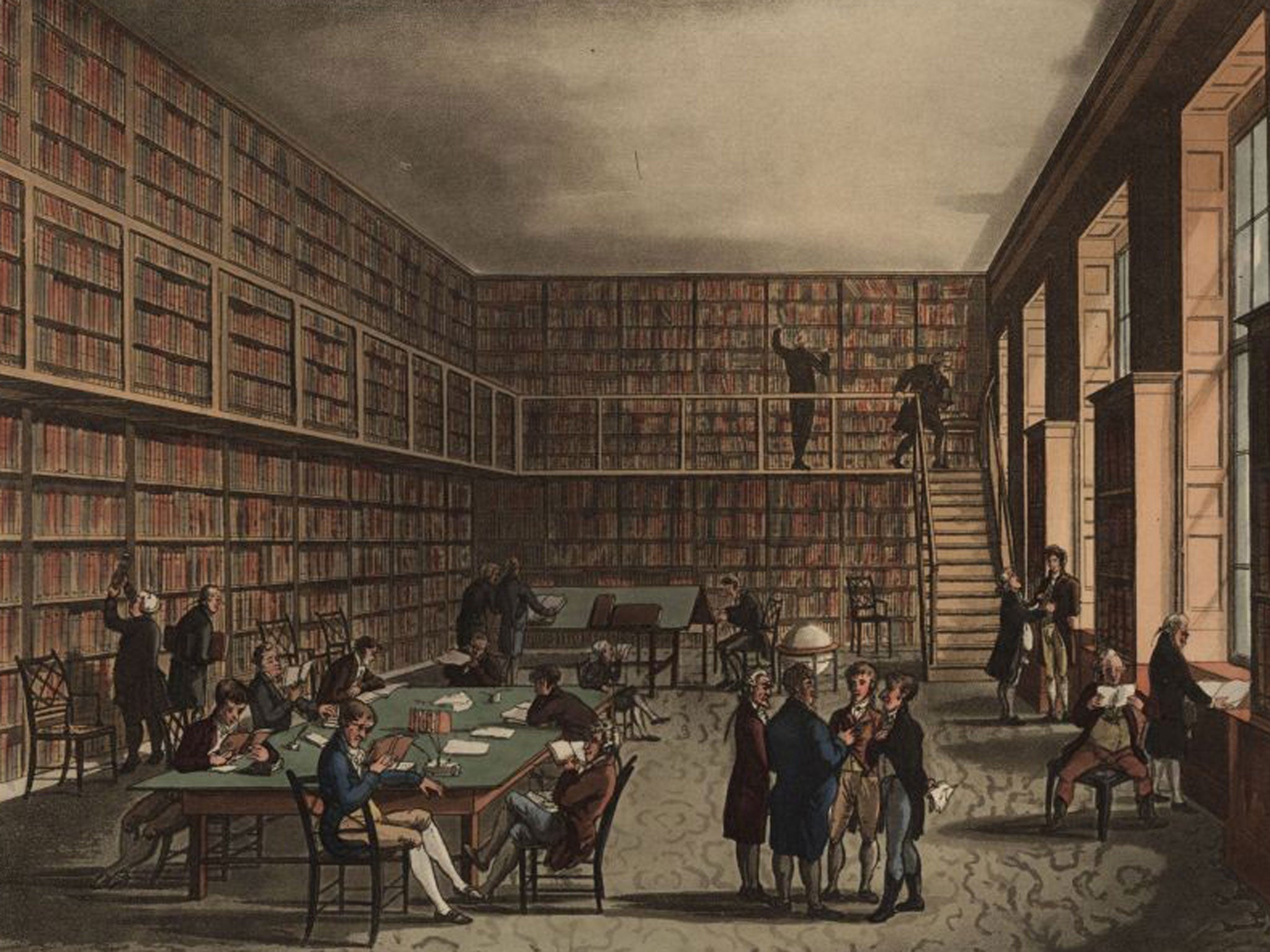

A story published on Thursday previewed the British Museum’s forthcoming exhibition of arts and crafts from Ming China. It includes some volumes of the earliest surviving encyclopaedia.

It’s a strange word, “tome”. Why do we need a special word for a big book, particularly when it gives off a whiff of derision? “Massive tome” is almost a cliché. It is difficult to imagine a “tome” being a good read. The Oxford Dictionary puts it thus: “Now usually suggesting a large, heavy, old-fashioned book.”

And when the word is used in a news story, there are no signals from the writer to tell the reader how to react. In the case of the Ming encyclopaedia, are we being invited to curl a lip at this huge, unappetising lump of medieval Chinese scholarship? Or is the writer just desperate for a synonym to avoid saying “book” again?

An analysis of the causes of the First World War, published on Wednesday, referred to the German plans “to outflank the French and whatever contemptuous little army the British might muster”.

Kaiser Bill is usually quoted as referring to Britain’s “contemptible little army”. It was the Kaiser who was contemptuous of the army. In a sense, though, it doesn’t matter, because it is apparently doubtful whether he said it anyway. The whole thing may be a misquotation or a piece of British propaganda.

An art review published on Monday told how, at a previous Surrealist exhibition, “eager visitors were invited to file past a living tableau in which a group of men and women dressed in the garbs of high fashion and prominent professions ate a fulsome meal from the naked body of a live young woman”.

Mark Miller writes in to ask what a “fulsome meal” might be. Good question. Presumably the writer meant a lavish meal. “Fulsome” generally refers to some kind of utterance, whether in speech or writing, that is gushing or over-polite. People rarely use the word properly, and mostly seem to think it means the same as “full”. Best avoided.

Steve Richards wrote in his Tuesday column: “There is a tangible sense that the [general election] campaign is under way.” That is not exactly wrong, but it is a sad example of the devaluation of a word. A mere “sense” is no longer strong enough; it has to be “tangible” – so strong that one feels one could reach out and touch it.

A picture caption on Thursday began thus: “A model presents a creation by Craig Green’s fashion house during a MAN show at London Fashion Week.”

“A model” pops up from time to time on the news pages. We don’t need to be told that the poor chap wearing the “creation” (which I will not attempt to describe) is a model. This is not a picture of the person, but of the clothes.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments