Do not adjust your TV. This election will be decided on the doorstep

There will be no uniform national swing but a hundred different local swings

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.So far, the election battle is over how the battle will be fought. The overwhelming question is whether there will be televised debates. The question triggers many others about the various permutations of those involved. There is also quite a lot of focus on the parties’ war rooms – which figures are meeting each morning and which are excluded. Another row is over whether some voters are wrongly excluded from the electoral register.

The form of the campaign overwhelms substance for a simple reason. The contest over policy is familiar and will not change. In contrast, the form the campaign should take is still to be resolved. In terms of policy, the Labour leadership has one final sensitive decision to make – about student tuition fees, how to pledge a reduction and what form that reduction should take. When asked about the issue Ed Miliband has at least twice said “Watch this space” in a way that will probably generate a sense of anti-climax when the policy is announced.

Meanwhile, George Osborne has to decide how far he can influence voters with tax cuts in his pre-election budget while still insisting that the economy is so precarious that unprecedented spending reductions are urgently required. But these additional policy statements will fuel a familiar narrative composed by leaders who were in place at the beginning of the parliamentary term and are still in place now. Elections are of supreme significance and all those entitled to vote should do. But the policy battle lines are not new and have been scrutinised for years.

The form of the contest is much less significant, but as a theme it is fresh, with daily twists and turns, even if huge amounts of space is taken up by an absurd debate about the TV debates. In an election campaign, leaders are fighting to win power. They are not taking part in an altruistic seminar to improve the minds of voters. In a way that is wholly justified, their calculations in relation to the debates are self-interested. They cannot admit this in public because leaders are not allowed to state the obvious without being slaughtered.

David Cameron has calculated rightly that he might lose out in the debates. He cannot state this, so he affects a sudden concern for the Greens, who are currently excluded from broadcasters’ plans. Ed Miliband and others who might gain from the debates argue – preposterously – that the broadcasters have the right to summon whichever leaders they want and the leaders have a duty to obey.

Why have the broadcasters acquired such a mighty right and why must leaders dutifully respond? Sky’s Adam Boulton insists that leaders must agree to take part out of a sense of public duty. Such a noble sentiment misunderstands what election campaigns are about. As far as any candidate is concerned, the objective is to maximise support and minimise backing for opponents, nothing else.

If the debates do take place they will be almost unwatchable when more than two leaders are involved. The last ones were dull and unavoidably formulaic with three. Only the novelty sustained interest. Debates with Cameron and Miliband alone could work well as the duo would have space to breathe, develop arguments and reveal, perhaps inadvertently, more about who they are.

When there are more than three participants, such potential insights become impossible. The events would be tediously one-dimensional, old assertions repeated one more time on an overcrowded stage. “You will put up taxes.” “You will take us back to the 1930s.” “No I won’t... and name me a big spending cut you would make to reduce the deficit.” “Let’s pull out of Europe.” “Let’s not.” “The Greens are the only ones worried about climate change.” “No, I worry too”. “Scotland’s being shafted.” “No, it’s not.” Thank you and good night. Crowded debates would be much worse than having no debates at all.

There is, though, another way in which form will matter hugely in the coming election and it is far away from a national TV studio. In an election that is as closely fought as this one and without a single distinct national trend, the battles at a local level are the ones that matter – the hard, unglamorous grind of campaigning in constituencies.

There was some evidence that resources used well in individual seats made a decisive difference in 2010. A model for Labour is the contest in Birmingham Edgbaston in 2010, held by their candidate, Gisela Stuart, when the Conservatives would have won with a tiny swing. Round-the-clock hard work, contact with many voters in every possible form and getting their supporters out on polling day were factors in what was a well resourced local campaign. The other parties scrutinise similar local successes, seeking to learn lessons fast and to apply them in target seats.

The lessons are not obvious. For many years leaders and their strategists have focused largely on the national campaigns – the advertising, the messages for the national media, the interviews and, last time, the televised debates. The techniques of modern national campaigns are well known – the artistry required of a national leader who hopes to connect with the electorate, the methods of dealing with a media still gripped by the need to “catch out” interviewees, the way to use social media in order to bypass biased newspapers.

There are a mountain of experts, some of them a lot better than others, who claim to be specialists in winning national campaigns and how to perform in the media. The local campaign is more of a challenge. Do voters read leaflets? Is Twitter an effective local medium? Do local newspapers still matter? Do as many listen to local radio as the unreliably collated audience figures suggest?

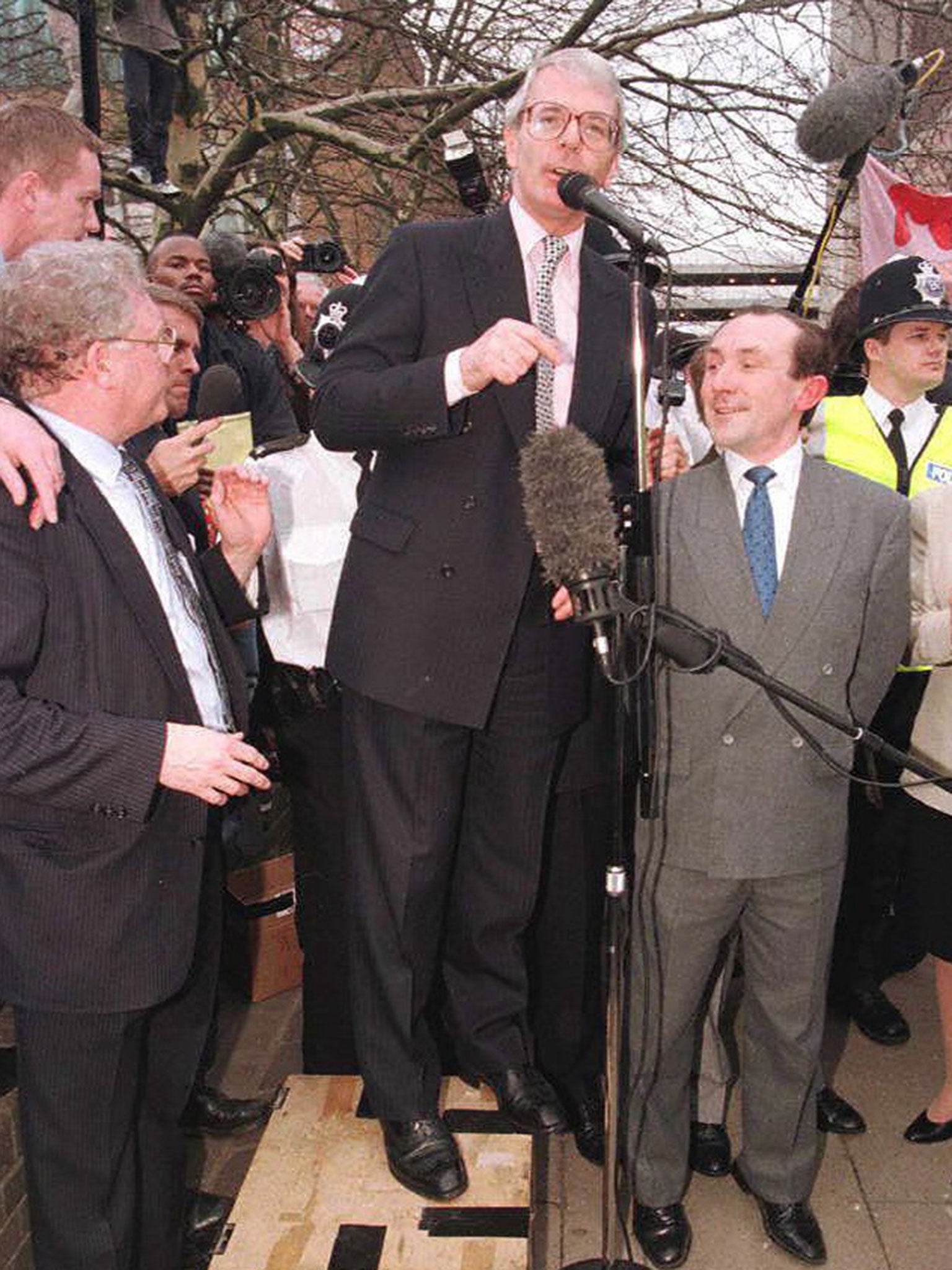

There have been old-fashioned national campaigns in the recent past, such as John Major preaching on his soapbox in 1992. But this election will be old-fashioned in a different sense. For all the focus on modern campaigning, the expensive importing of President Obama’s advisers and the rest, this will be a contest decided by what happens on the ground in different constituencies almost irrespective of the national battle. There will be no uniform national swing, but a hundred different swings.

We know what all the parties are proposing in terms of policy and if there are televised debates we will find out all over again. We do not know which ones will be most effective on the ground. The ones that are will flourish in May.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments