Despite what the Government says, people are not better off. And the self-employed are likely to be suffering more than most

More self-employed report that they do not have adequate work and want more hours

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The battle over what is happening to living standards continues. They are down a lot under the Coalition, despite its spin saying they are up – which they demonstrably are not, as I have noted several times in this column.

In The Times on the 24 January, Matthew Hancock, the minister for skills and enterprise, argued in a column entitled It’s True: We’re Better Off than a Year Ago that “over the past year, from 2012 to 2013, things have started to turn around. New facts on take-home pay – the pound in your pocket – are stark. Last year take-home pay grew faster than inflation for every group of earners except the top 10 per cent.”

This claim turns out to be total baloney. Real wages, and hence standards of living, are falling, and continue to fall for all but a few at the top. These falls have been tempered for home owners by the drop in the interest rate on their mortgages.

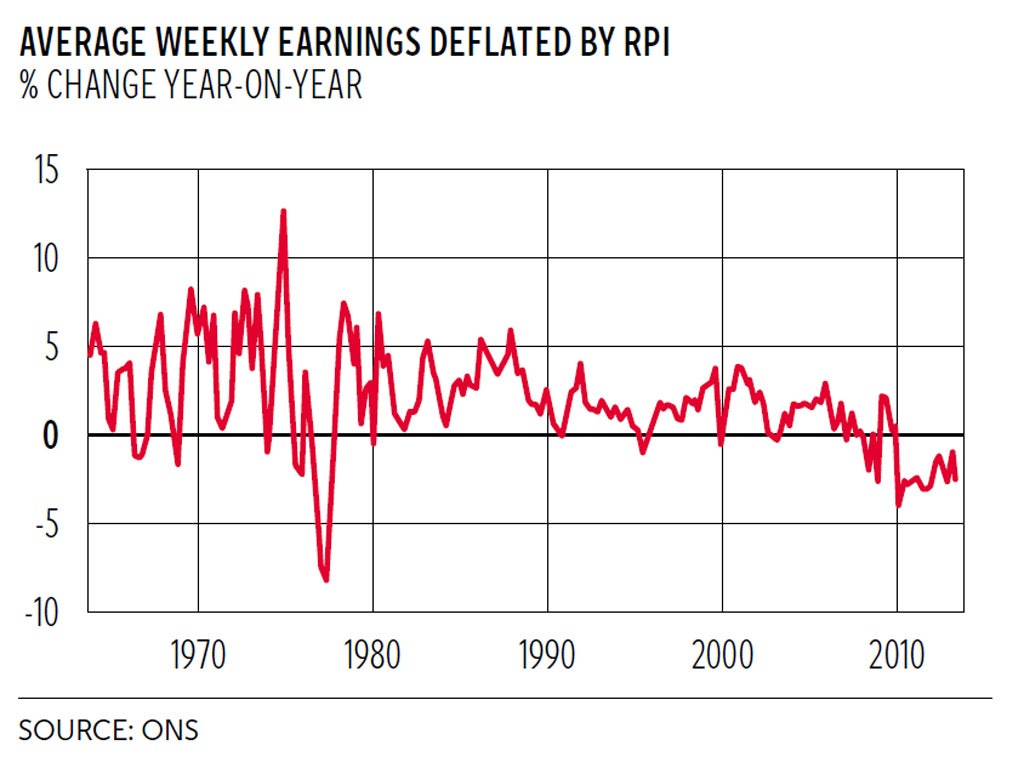

In response to such ludicrous claims last week, the Office for National Statistics published a response showing exactly the opposite. The chart below, taken from the ONS study by Taylor et al*, plots real wage growth since the first quarter of 1964 based average weekly earnings (AWE) deflated by the Retail Prices Index. It shows the percentage change on the same quarter a year earlier. Annual real wage growth averaged 2.9 per cent in the 1970s and 1980s, then roughly halved to 1.5 per cent in the 1990s. The rate slowed again to an average of 1.2 per cent in the 2000s, and real wages fell by 2.2 per cent a year between Q1 2010 and Q2 2013, so are down by more than 6.5 per cent since the Coalition took office.

There is no chance that this decline in real wages will be restored by the time of the May 2015 election, even if real wage growth turns positive at some point over the next 15 months or so, which still looks unlikely. The chart also shows that the recent episode of falling real wages under this Coalition is the longest sustained period of falling real wages in the UK for 60 years. No other episode comes close.

According to the Labour Force Survey, nominal wages are falling at both the median and the mean for full-time workers. So Hancock is badly wrong, sorry – and that’s official as the ONS has confirmed it. Plus Hancock’s claim takes no account of the cuts to in-work and family benefits the Coalition has introduced, or the rise in VAT. The Institute for Fiscal Studies also warned in its Green Budget last week that there are many more cuts to come.

There are additional concerns about living standards given that we have no recent estimates of the earnings of the self-employed as they aren’t covered by the ONS in any of its published wage and earnings series. This matters given the rapid rise in the numbers of self-employed since the coalition was formed in May 2010.

In April-June 2010, there were 24,830,935 employees and 3,923,724 self-employed; in the latest data for September-November 2013 there were 25,536,595 employees (plus 705,660) and 4,355,819 self-employed (plus 432,096). So even though self-employment today accounts for only 14 per cent of total employment, it accounts for more than a third of the increase over this period.

It turns out that there are a number of things we know about self-employment. The first is that higher self-employment rates appear to be uncorrelated with any positive macro outcome, so a higher proportion of self-employed doesn’t seem to be associated with higher output or lower unemployment.

Even though in theory a higher self-employment rate suggests increased labour market flexibility, a higher self-employment rate doesn’t mean that a society is more entrepreneurial, for example.

An extra 200,000 new self-employed workers may not be as entrepreneurial as one more Bill Gates. It also turns out that despite the fact that mean self-employment earnings are higher than mean employee earnings, this is driven by the fact that the mean is pulled up by a higher top end. The typical self-employed worker earns less than the typical employee, plus we should note that self-employed earnings are not bounded above by zero but can include negative values or losses.

When asked, approximately half of employees say they would like to be self-employed, but most don’t make the switch. Being self-employed is risky, and huge proportions fail. They then lose their jobs, their savings, sometimes their homes and not infrequently, their marriages. Self-employment is an inherently risky, low-paying activity that most people should avoid if only for their mental health. Those who succeed can make a lot of money and that is the attraction, of course. But most don’t.

In a recent paper, Richard Murphy** has made use of data on self-employed earnings from HMRC up to 2010-11 based on how much the self-employed say they earn. This is the main source for data on self-employed earnings, which is sadly not terribly recent. Mr Murphy first notes the remarkably low level of income that a great many of the self-employed earn.

He found 83 per cent reported incomes of less than £20,000 in 2010-11, with 14 per cent earning zero or negative while 95 per cent earned less than £50,000. Less than 2 per cent earned over £100,000. Mr Murphy also notes the decline in the income over time for the self-employed, which suggests that the earnings of the self-employed have also fallen recently, both in nominal and real terms.

So excluding the earnings of the self-employed may mean the extent of the drop in living standards has been understated as their earnings are likely to be more flexible downwards than that of employees. Indeed, there is evidence that a considerably higher proportion of the self-employed than employees report that they are under-employed, do not have adequate work and want many more hours.

The Labour Party will be able to claim: You are worse off under the Tories in May 2015 than you were in May 2010.

*Ciaren Taylor, Andrew Jowett & Michael Hardie, An Examination of Falling Real Wages, 2010-2013, Office for National Statistics, 2014

**Richard Murphy, Disappearing Fast: The Falling Income of the UK’s Self-employed People, Tax Research UK, November 2013

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments