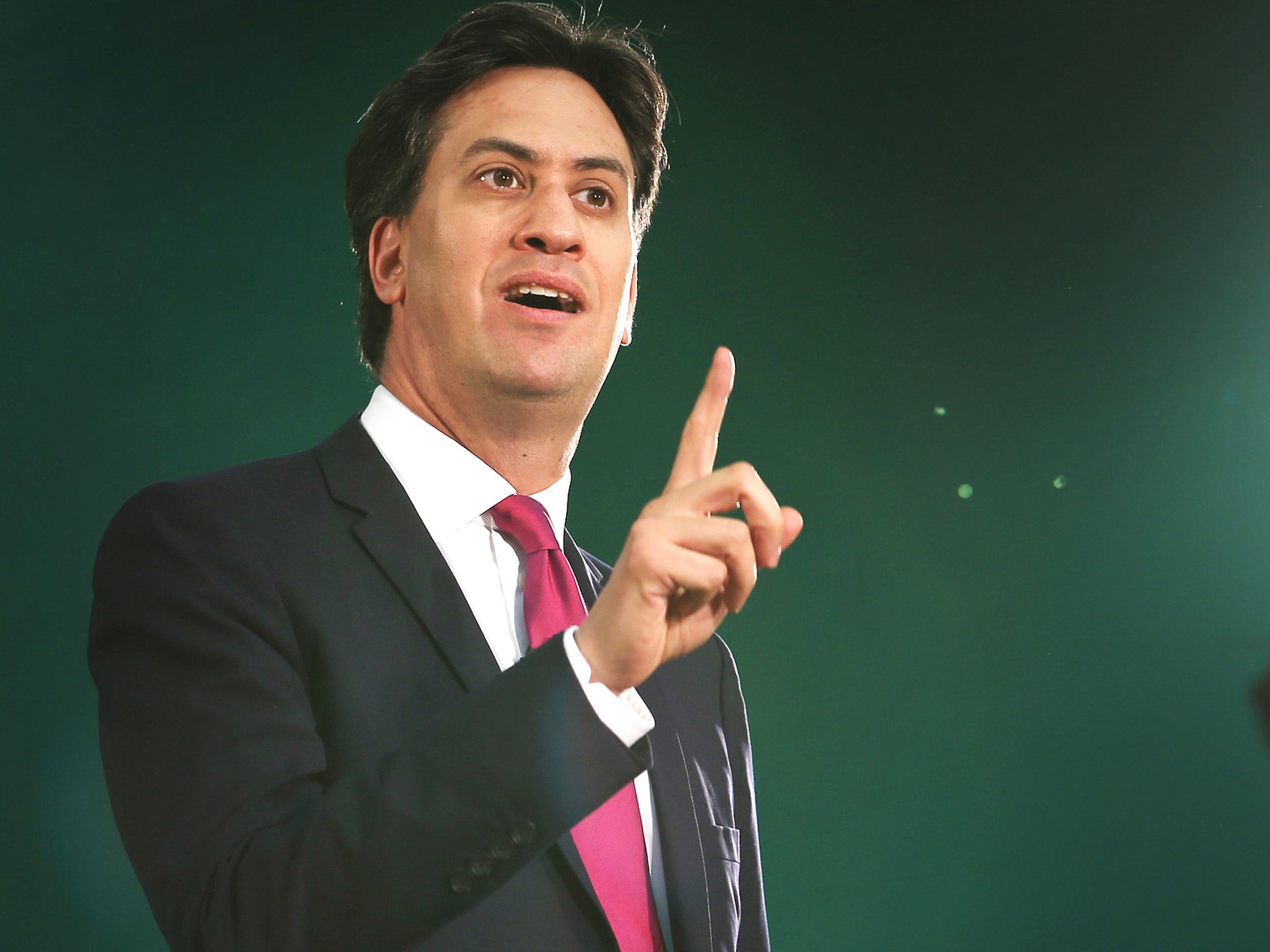

Despite new plans, Miliband isn't taking an axe to welfare

Labour needs to adapt its policies to the changing attitudes of the British public towards welfare

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 2010, I attended the annual conferences of the three main political parties. I found the Lib Dems to be in a confused state – their leadership out of kilter with the grassroots, but excitement overall at the prospect of power. The Tories were grumbling: they’d not won the outright victory they thought they merited; and they remained unconvinced by David Cameron.

By far the most buoyed of the three was Labour. I was expecting to find doom and gloom at conceding government after 13 years. Instead, there was a cheerful, earnest energy about the party. I expressed my surprise to a senior Labour figure who said that I forgot something: unlike the other two, Labour is a movement; it had experienced a setback, that was all, the journey continued. In the past they had lost elections and descended into splits and civil war; not now.

That was four years ago, and next year Labour must face the electorate again. Much has happened in that period, in particular the public acceptance of the need for austerity – of radical measures, of swingeing cuts, and the need to try to rebalance the books. Now, after the pain, the economy is beginning to motor again.

Labour cannot just pick up where it left off. It may be a movement but it’s lost its sense of direction.

Historically, it’s the party of welfare. But Britain has changed. There’s less money to go around. Attitudes have also hardened. An electorate that has endured much is not prepared to tolerate anything any longer that could be interpreted as acceptance or even tacit encouragement of scroungers.

It’s this realisation that lies behind Labour’s move to deny out-of-work benefits to unemployed young people unless they agree to training. Those aged 18-21 would no longer qualify automatically for jobseeker’s allowance. They would only receive it if they had Level 3 skills, which include A-levels, AS-levels and vocational equivalents, or they undertook further education to attempt to reach that level.

Even then, it would be means-tested and only be paid if their parents’ joint income was less than £42,000 a year. In addition, they would be expected to live with their parents rather than claim housing benefit. Ed Miliband calls it “tough love”, a plan that is “progressive, not punitive”.

Under the existing system, what often riles people is that if they’ve been working all their lives and paying taxes throughout, when they lose their jobs, they’re entitled to no more than someone who has worked for just two years.

Labour wants to restore the principle of Sir William Beveridge, architect of the welfare state, that the more you put in, the more you’re able to get out. So, those in work for five years will receive £100 a week, versus the present £72.40.

Will it be enough? It’s certainly a major step, a reversal in policy that now makes it very difficult for anyone to accuse Labour of being soft on skivers. The shift will result in an estimated net saving of £65m a year – again, countering the charge it’s the home of increased public expenditure. The reaffirmation of Beveridge, and the ending of “nothing-for-something” is a radical departure and will be hailed as evidence that Labour really does care about, and rewards, hard work and enterprise.

With it all, however, is a sense of tinkering, of finding ways of keeping the present flawed framework going. What Labour is not doing is taking an axe to welfare. Arguably, a Tory alternative of just slashing jobseeker’s allowance, and using the much-reduced payment as an incentive to securing employment, would be simpler and more easily understood.

There’s a feeling of Labour not wishing to let go, of failing to fully appreciate the depth of hostility towards the “something-for-nothing” culture.

The proposals are contained in Condition of Britain, a wide-ranging report from the IPPR think-tank on how to create a fairer society in an age of austerity and increased inequality. It’s recognition by Labour that its hitherto favoured method of raising taxes to pay for higher spending is moribund.

Labour’s policy review chief Jon Cruddas has likened the switch to the “Burning Platform” email sent by the then chief executive of Nokia, Stephen Elop, to the company’s staff in 2010.

It was a missive that attracted attention for the fact that Elop bared his soul – something that rarely occurs among corporate titans. He likened himself to a man asleep on a North Sea oil platform, and woke up to find it engulfed in flames. He had a choice: to stay and perish or leap into the freezing waters 30 metres below. Ordinarily, he would never jump but these were not ordinary times. He took the plunge and after he was rescued, “noted that a ‘burning platform’ caused a radical change in his behaviour.” Something similar was now required at Nokia.

It’s an analogy, however, that gives some indication of the dilemma Labour now finds itself in. It should not be forgotten either, that Elop’s stirring rhetoric made no difference. Nokia profits went on to fall 95 per cent, the Finnish giant’s market share crashed, its share price plummeted, and the mobile phone arm was eventually taken over by Microsoft, with Elop reduced to the rank of executive vice-president. I wonder what fate awaits Mr Miliband?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments