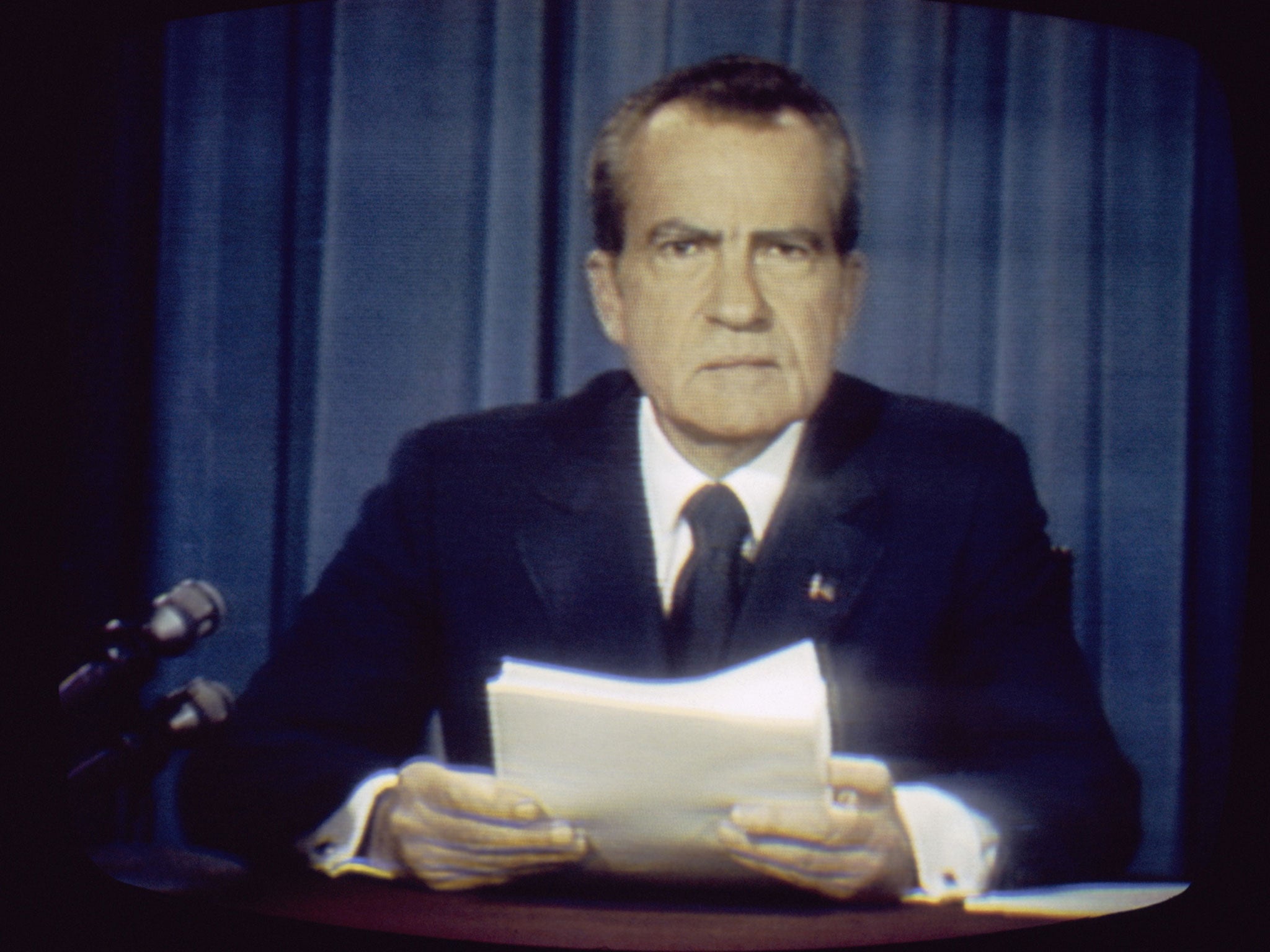

Democracy is... saying goodbye without the gunfire

Richard Nixon managed it, and his party soon returned to power. The lesson from the Cairo coup last week could not have been more different

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Let us start with a compare and contrast exercise in the downfalls of national leaders – between downtown Washington DC on the evening of 8 August 1974, and Cairo, on pretty much any evening last week.

In the first instance, a Republican president was being forced from the office to which he had been re-elected less than two years earlier. Richard Nixon's fierce opponent Tip O'Neill, the future Democratic Speaker of the House, driving past the White House, was struck by the extraordinariness of the moment. "Isn't this the damnedest thing you ever saw," he remarked. Inside, the most powerful man in the world was ceding power. Outside, no protesters, no riot police, no tanks. Just a single policeman directing traffic in the gathering dusk.

The overthrow of Egypt's Islamist, but no less properly elected, president by the generals could not have been more different. In Cairo, there were massive demonstrations, as soldiers fired on Mohamed Morsi's supporters while his opponents rejoiced in the streets. In Washington, power passed smoothly to Nixon's constitutionally designated successor. In Egypt, the choice now seems to lie between a junta and civil war.

Make no mistake about what has just happened. Call it a "benign" coup or a "soft" coup, or merely the army's response to the overwhelming demand of the people – this was a military coup. Yes, Morsi made a mess of things, but in democracies, you change leaders at the ballot box, not through the barrel of a gun.

If Egypt is lucky, things could yet not work out too badly, along the lines of the 1997 coup in Turkey that overthrew the then Islamist government. But consider a worst-case scenario, Algeria 1992, when the military cancelled elections an Islamist party was set to win, plunging the country into a decade of ghastly violence.

But let's return to Washington 1974: why didn't the tanks roll and protesters storm the White House? That's not the way things are done in western democracies, is the instant, unthinking answer. But why not? Because – and this is the real difference between us and not only Egypt but a host of other countries in the Middle East and beyond – the parties vying for power have so much in common.

Yes, Republicans and Democrats, Conservatives and Labour, Christian Democrats and Social Democrats have their quarrels. But what unites them is far more important: a belief in a secular society, the rule of law and the market economy; a reasonably fluid and meritocratic social structure, and the acceptance of a role for government. To be sure, opinions on the correct size of that government differ, as the seemingly eternal political gridlock in Washington testifies. But the fashionable talk of US "ungovernability" is nonsense. If it's ungovernability you're after, go to Syria, Egypt or Iraq.

It's easy to be cynical about the way western democracy works – not least because of the self-congratulation and hypocrisy in which it's so often cloaked. Alternation in power, it is rightly said, is possible only because alternative models of society are not in play. The political failures in Egypt and Syria provide opposite proof of that principle – when truly alternative models are on offer, be they religious or ideological, political alternation is impossible.

At the most basic level democracy, as we in the West understand it, works only because of a trust shared by both government and opposition: that if the other lot wins power at an election, your lot will have the chance to win it back. Coups, of course, by their nature, have throughout history mostly worked against alternation. Hitler might have imposed his dictatorship from within government, but it was a coup nonetheless, underpinned by an enabling law that gave the Nazis total power and enforced by savage thuggery. The most momentous coup in modern history, in Petrograd in October 1917, banished the alternation of power completely, until Soviet Communism imploded in 1991.

From this perspective, the greatest failing of the Middle East's repressive military-backed regimes – their refusal to allow the development of a significant opposition – is obvious. Whatever opposition that did survive was clandestine and radicalised, making it even more likely that it would be demonised and persecuted by government.

But the collapse of communism and the Arab Spring has shown that no autocratic regime survives for ever. Fortunately, much of eastern Europe had old democratic traditions to fall back on. Not so the Arab world where organised oppositions simply did not exist to fill the vacuum, as the Syrian tragedy proves.

Egypt, the most important country in the Arab world, offered a chance to break this dismal pattern. But that chance may well have been thrown away by last week's coup, with grim implications for the region. President Morsi and his Islamic Brotherhood might have governed badly, but they might also have been removed from power at the next election. Now they, and Islamic movements everywhere, will have concluded that playing by the rules is pointless. Inevitably, they will become more radical. And as for an 8 August 1974 Washington DC moment in Cairo, forget it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments