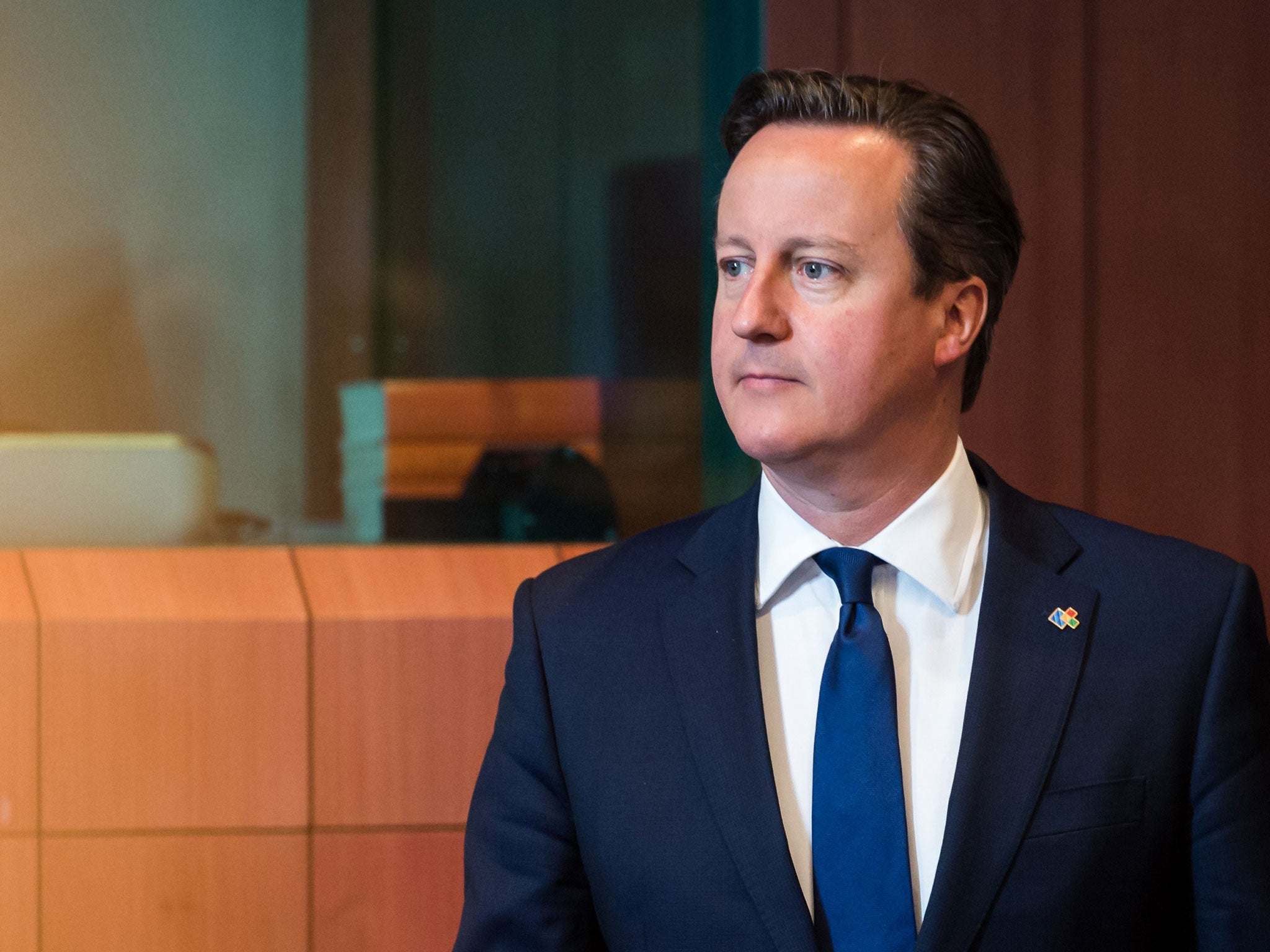

David Cameron’s legacy depends on making Big Society work

But how can government help to restore values of community and trust in a society whose free enterprise ethic seems to brush them aside?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Almost unnoticed, David Cameron has become the giant-killer of British politics. He has consigned a whole generation of political leaders to the wilderness – Kenneth Clarke, David Davis and Malcolm Rifkind in 2005, Gordon Brown in 2010, Ed Miliband and Ed Balls and the Labour Party in 2015, together with Nick Clegg, Vince Cable, David Laws, Simon Hughes and almost every other Liberal Democrat MP.

Cameron has always been underestimated. When he stood for the leadership in 2005, he was seen as an outsider with little chance. Ten years later, he is potentially master of all he surveys. Labour is in disarray while the Lib Dems hardly exist. The political cemeteries are littered with those who underestimated him.

But Cameron is also underestimated as a political strategist. Because he is not ideological, it is assumed he lacks a strategy, that he is a lightweight, a mere PR man. That too is mistaken. At Oxford, Cameron gained an outstanding first-class degree, one of the best of his year. In office, he retains his intellectual curiosity, the product of careful reflection and wide reading in history and politics. But, unlike some, he doesn’t feel impelled to parade his learning. He is well aware the British people distrust intellectual display. It is a healthy instinct. When we go to a concert, we do not want to be reminded of how hard the pianist has practised. All we care about is the quality of the performance. An air of ease always inspires confidence.

Cameron, unlike Margaret Thatcher, is not an ideological Conservative. The UK no longer needs one since the dragons (inflation and excessive trade union power) have long been slain. His Conservatism is practical and non-ideological, like that of the Prime Minister he most admires, Harold Macmillan.

Perhaps the instinct which most strongly moves him is that individuals should be free to live their lives as they think fit. That is what made him so strong a supporter of gay marriage. His concerns about the EU may have less to do with worries about sovereignty than with the fear that Europe seeks to interfere too much in the nooks and crannies of everyday life. It is the liberal instinct that inspired the slogan for which Cameron is best known – the Big Society.

“There is such a thing as society,” he said, in an implicit rebuke to Mrs Thatcher, after being elected leader in 2005. “It’s just not the same thing as the state.” In his Hugo Young lecture in 2009, he answered those who “say they don’t know what I stand for”. His agenda was “aspiration for a Big Society, social service, education and welfare reforms”. But does the notion of The Big Society have any content – or is it, like The Third Way, just another exhibit from the repertoire of political slogans?

Stripped of rhetoric, the Big Society comprised three ideas. None was wholly novel, and all are rooted in Conservative traditions. The first is decentralisation, an idea that fits happily with George Osborne’s Northern Powerhouse project of devolution to city regions with elected mayors. The second is an emphasis on voluntary rather than state action. The third is the idea – first championed by John Major, but adapted by Tony Blair – of empowerment, competition and choice in the public sector.

But the Big Society faces two problems. The first is whether it offers sufficient succour to the victims of Conservative policies directed towards a smaller state and retrenchment in public spending. They are unlikely to receive much help from local authorities or the Salvation Army; and those hard-pressed by austerity are unlikely to have much time to act as volunteers.

During the early 20th century, it was the very inadequacies of provision by local authorities and volunteers that made for the growth of the state. Every Conservative government since the war has tried to roll it back, without success. It has again become fashionable to decry the state. Nevertheless, it is where we turn when we find ourselves sick, disabled or out of work.

The second and deeper problem with the Big Society is that it conflicts with the economic liberalism to which Conservatives are also committed. Capitalism, after all, is a radical, destabilising force. It undermines the traditional props of Conservatism – family, community and society.

This conflict between the values of competitive capitalism and social stability was first noticed by Keith Joseph, Mrs Thatcher’s John the Baptist, in the 1960s. As housing minister, he was shocked to find the divorce rate rising among slum dwellers after being rehoused. The security of a home gave couples a chance to reappraise their relationships. And many found them wanting.

So prosperity may lead not to a more stable society, but to a more volatile one.

Capitalism sanctifies the entrepreneur, but is in danger of producing a society dominated by the cash nexus, reducing human relationships to a calculation of interest, so undermining social responsibility. One critic rather unkindly said of Mrs Thatcher that, whereas she aimed to create a society in the image of her father, the frugal shopkeeper, the one she in fact created was more in the image of her yuppie son. The banking crisis of 2008 offered a stark illustration of the fact that a sense of social responsibility was not one of the more obvious characteristics of the beneficiaries of Thatcherism.

How can government help to restore values of community, trust and responsibility in a society whose free enterprise ethic seems to brush them aside? That is Cameron’s problem as he seeks to put his generous Macmillan-esque instincts into practice. It is one Keith Joseph never resolved. Indeed Michael Foot once compared Joseph to a conjuror at the fair who took your watch, wrapped it in a handkerchief, smashed it with a hammer, but then confessed that he had forgotten the second half of the trick.

Cameron’s second term will be judged not only by whether he maintains the economic recovery but by whether he can reconcile prosperity with community responsibility, with the Big Society. He will be judged by whether he can remember the second half of the trick.

Vernon Bogdanor is Professor of Government, King’s College, London

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments