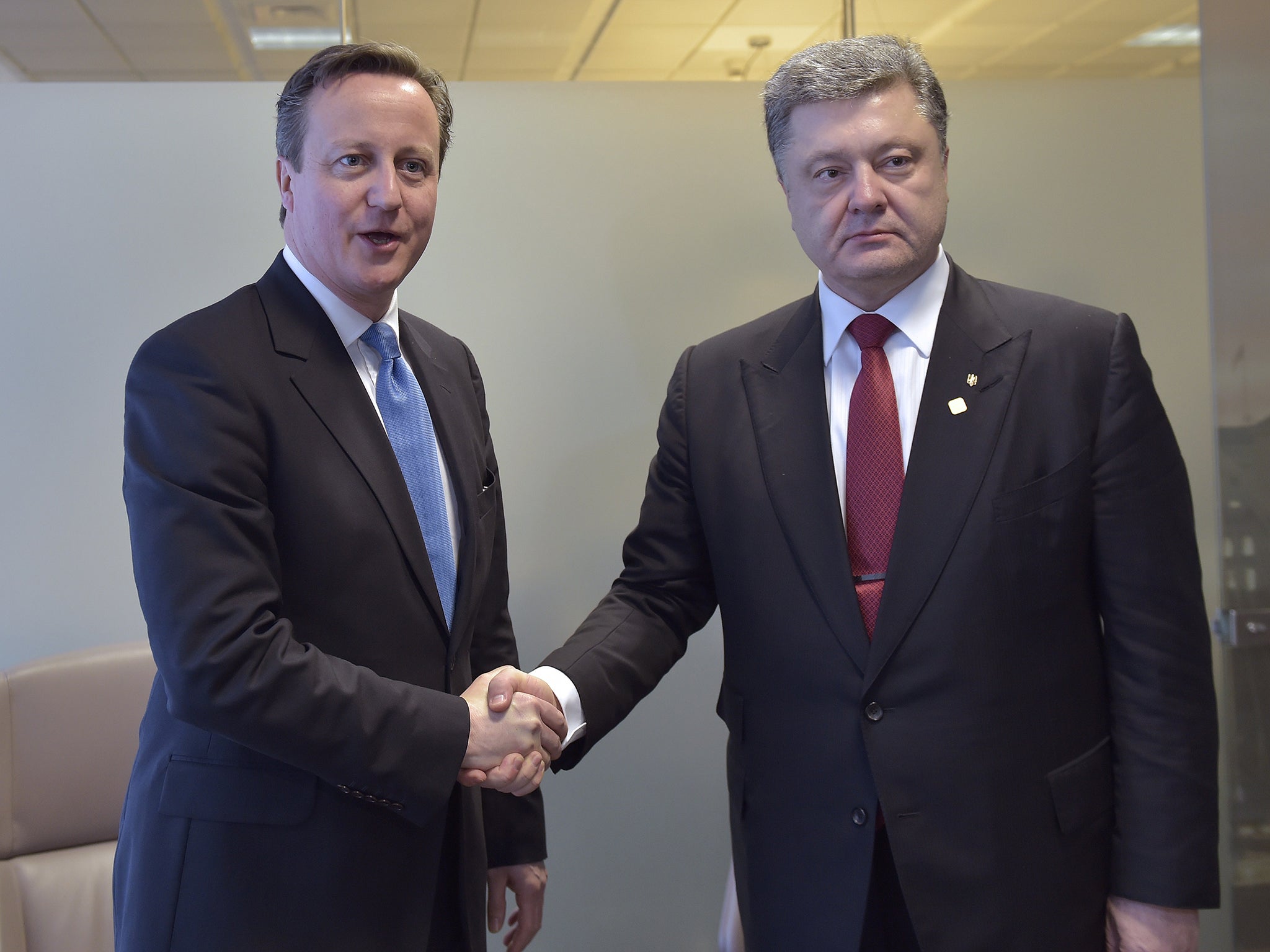

David Cameron talks big but is waving a small stick at the Russian bear

Diplomatic Channels: Some believe Mr Cameron’s desire to jump in over Ukraine came in response to charges that he has become a nonentity in the crisis,

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.David Cameron, according to his critics among senior diplomats and military commanders, seems to have turned Teddy Roosevelt’s advice on foreign policy – “speak softly and carry a big stick” – on its head.

The Prime Minister’s sudden announcement of sending military personnel to the Ukraine is in line with that of the leader who sees himself as the strategic supremo. When some senior officers raised doubts over air strikes on Libya three years ago, he declared: “I tell you what. You do the fighting and I’ll do the talking.”

Mr Cameron does not talk about Libya much nowadays, of course. And the failure to help stabilise the situation after the fall of Muammar Gaddafi, the repeated demands that Bashar al-Assad should go without giving meaningful help to the Syrian moderate opposition, and then sending a minuscule force to Iraq to fight Isis, may not fill one with confidence about a Ukrainian adventure.

The reason the Prime Minister’s stick will continue to shrink, so to speak, as he continues to talk loudly, is the shrinking defence budget. The head of the US military, General Raymond Odierno, publicly expressed his concern about the UK’s defence cuts.

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with the concept of sending trainers to Ukraine. It is better than sending heavy weaponry to a relatively untrained force, with its complement of private militias, as some in Washington were threatening to do. But the Americans already have a long-arranged plan to send a force of about a thousand to do that training in the next few weeks.

The UK will send 75 military personnel to Ukraine. The total ground force in the anti-Isis mission, in Iraq, is around 70. A recent report by the Commons defence committee was highly critical of the efforts there. On a visit to the region, the MPs found there were only three UK personnel outside the relatively safe Kurdish areas, compared with 400 Australians and 280 Italians, let alone the Americans. The RAF, they discovered, had carried out just six per cent of the strikes.

Some commanders and diplomats believe that Mr Cameron’s desire to jump in over Ukraine came in response to charges that he has become a nonentity in the crisis, with German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President François Hollande brokering the Minsk ceasefire agreement without the UK being involved.

The caustic criticism of General Sir Richard Shirreff, formerly the UK’s most senior commander in Nato – “Where is Cameron? He is clearly a bit-player. Nobody is taking any notice of him. He is a foreign-policy irrelevance” – is said to have stung No 10.

Sending the troops must have been signed off by General Houghton, the Chief of Defence Staff. One must not feel too sorry for the military over this; the decision to deploy may have come from Downing Street, but it does show they are needed; similarly, the more Russian Bear bombers to see off around British airspace the better for the RAF in the time of cutbacks.

But the cutbacks remain a looming shadow. The UK’s defence spending meets the Nato threshold of two per cent of GDP, but only just, according to MoD figures, and has actually fallen in real terms according to independent estimates. In any case, the Government is committed to this only until the end of this Parliament.

General Odierno was graphic about what a future war might hold. “In the past we would have a British army division [around 20,000-strong] working alongside an American division. Now it might be …. even a British battalion inside an American brigade.” To put that in context, a battalion is what the Americans are sending to train the Ukrainian forces.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments