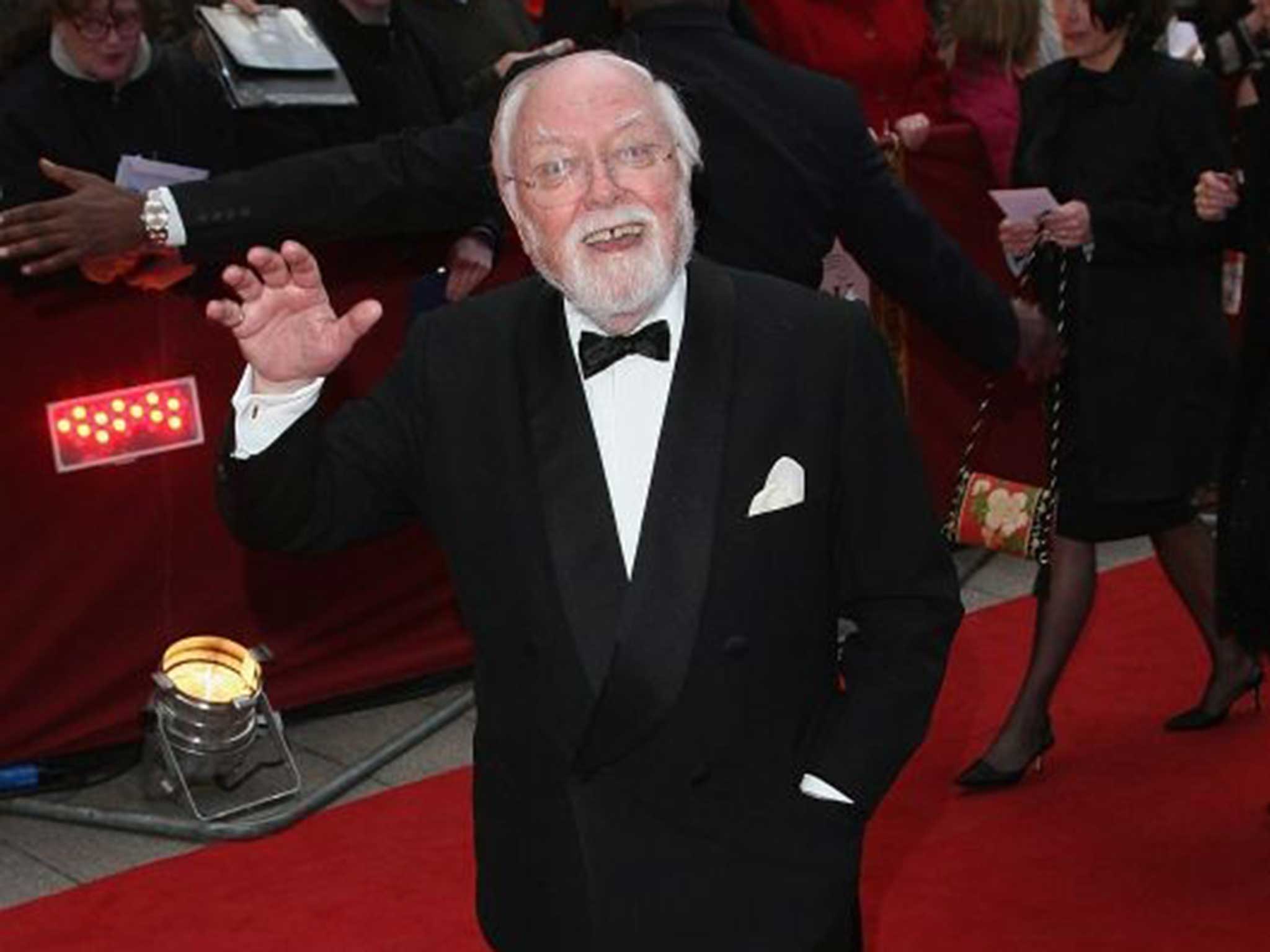

Daddy, who was Richard Attenborough? Was the beloved thespian the last of the cross-generation stars?

The atomisation of culture means that few of those we regard as stars are universally loved any more

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.According to press reports, the general paper of the All Souls College Oxford prize fellowship exam has become less abstruse than in the period 20 years ago when candidates were expected to write for three hours on a single abstract noun. If this is so, then a good question for this October's band of aspiring academics might be the following: "Discuss, without recourse to patronage, the connection between the death of Lord Attenborough and the recent series of concerts performed in London by Kate Bush with particular reference to audience, shared knowledge and the diffusion of 21st-century cultural taste.'

The death of Lord Attenborough at the ripe age of 90, beloved by every thespian who had ever trod the boards with him, produced a kind of media coverage not often seen these days, the sense that here, given the scope and longevity of the deceased's career, was someone with a well-nigh universal appeal and relevance. At the same time, these lavish memorials to the edginess of his performance in Brighton Rock (1947) or the extraordinary persistence that realised the Gandhi project, coincided with a suspicion that to younger readers and viewers his status rested almost entirely on late-period hokum such as the Jurassic Park franchise and Miracle on 34th Street.

It was the same, up to a point, with Ms Bush's return, after a 35-year absence, to the stage of the Hammersmith Apollo: an event trailed through the arts sections of broadsheet newspapers for weeks in advance, the subject of reverential TV profiles and adoring reminiscences courtesy of every 1970s pop idol from Elton John to the Sex Pistols' Glen Matlock. And yet, as the smoke rose, the dancers dispersed and the critics tumbled prostrate to the floor of the venue's press box, it became clear that the constituency taking an interest in the phenomenon, though large and vocal, was pretty much confined to the over-45s. Ms Bush may have her younger fans, but universal entertainment this patently is not.

All of which raises the question of whether universal entertainment of the kind which 30 years ago found half the UK population tuning in to particular television shows and sporting events exists any more, and whether – to extend the scope of the enquiry a little further – there is such a thing as shared cultural knowledge, here in a landscape where the sheer volume of artefacts available defies any reasonable attempt to assimilate them. Forty years ago, after all, you arrived in the school playground ready to discuss the television programmes you had watched the night before secure in the knowledge that there were only three channels. In a world where everyone has access to everything, the old communality of songs whistled in the street and collective tears shed at the news of Grace Archer's death has disappeared, save in very exceptional circumstances.

The same rule, alas, applies to that shared understanding of the environment you are born into which used to be such a feature of British life. It is difficult to make any judgement on this complex subject without sounding like the worst kind of cultural snob, but the evidence of such reliable yardsticks as the TV quiz show suggests that, whatever one may feel about these gaps, there are a whole lot of people out there who know a whole lot less about the place they wander about in than did their predecessors, and that information which was regarded as basic and inviolable half a century ago (geography, for instance, or bedrock-level history) is now seen as a kind of optional garnish, certainly not as important as the ability to navigate your way around cyberspace.

No doubt, much of this divide is, as it always was, generational. Watching the ITV quiz show Tipping Point with my 14-year-old son the other day, I professed the usual fiftysomething's pious horror at what seemed to me the ominous levels of ignorance on display: the participants who thought Harold Macmillan was a Labour politician or that Beatrix Potter's books were set in Hyde Park. This, Leo patiently explained, was because they were under 35: the middle-aged contestants on Pointless over on BBC 1 were much more likely to know that Mary Tudor was the daughter of Catherine of Aragon. On the other hand, you have an idea that the 35-year-old of 30 years ago would probably have heard of, say, Clement Attlee and Aneurin Bevan.

What might be called the atomisation of contemporary culture has several explanations. One of them is that past time is rarely presented to children as a continuous entity, but seen in terms of one or two fashionable periods, with the result that there are thousands of 19-year-olds with A-levels in history who have never heard of Cavaliers and Roundheads or know what F D means on a penny. Another is the almost exponential profuseness of the material, in which, for example, each category of popular music sub-divides into dozens of constantly mutating sub-genres, all of which would take a row of text-books to comprehend. The third is the widespread diffusion of that tantalising abstract "taste", which has been going strong since at least the middle of the 19th century.

Some idea of what happened to "taste" – here defined not as "the expression of a shared opinion", but "the expression of a shared opinion which those sharing it believe to be correct" – can be gauged from its development in the narrower field of literature. In the early Victorian age the reading public was not more than a few thousand strong, with the result that the concept of literary appreciation rested – up to a point – on mutually agreed standards. But with the educational reforms and the publishing revolution of the later 19th century there came into being a mass reading public, whose interests and instincts were very different. Highbrow fought middlebrow, and the "taste" of the Eliot and Joyce-fancying modernist was – at any rate to the reader who preferred J B Priestley – seen as a kind of conspiracy designed to make the man in the street feel small.

A century on, the idea of a shared body of knowledge – Eliot's "objective correlative", by which readers form disinterested views of books based on the information acquired over a lifetime's study – is dead and gone, for there are reviewers out there on Amazon whose idea of a "classic" is Stephen King, and are sometimes unable to determine whether the work before them is a biography or a novel (I am not making this up – it happened with Amanda Foreman's Georgiana Duchess of Devonshire).

Does any of this fragmentation, whether in the world of literature, cinema or music, actually matter? And who cares if a child has ever heard of Oliver Cromwell? On the one hand, one need only to look at some of the prescriptive critics of a bygone age – F R Leavis, say – to think that a world where people make their own choices about the kinds of culture they want to participate in is a good thing. On the other, if nearly 70 million people are having to live in harmony on the same increasingly overcrowded island, then the more things they have to bring them together rather than draw them apart and the greater the feeling of shared cultural context the better.

And so, while a small part of me thinks that the failure of all but one of the England World Cup squad to recognise Morrissey when they came across each other at an American airport in the summer is entirely foreseeable, another part wishes fervently that Wayne, Lamps and Stevie G had queued up to shake his hand.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments