Cameron is targeting the wrong jobsworths

The furore over George Entwistle's payoff from the BBC highlighted the absurdity of huge employment contracts that reward mediocrity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I agree with Dave. I have no truck with Britain’s entitlement culture. There, I’ve said it…except that I’m talking about a different category of person to those targeted by the Prime Minister. The jobsworths and low achievers I refer to are a senior management class that for decades has operated under a gold-plated employment culture.

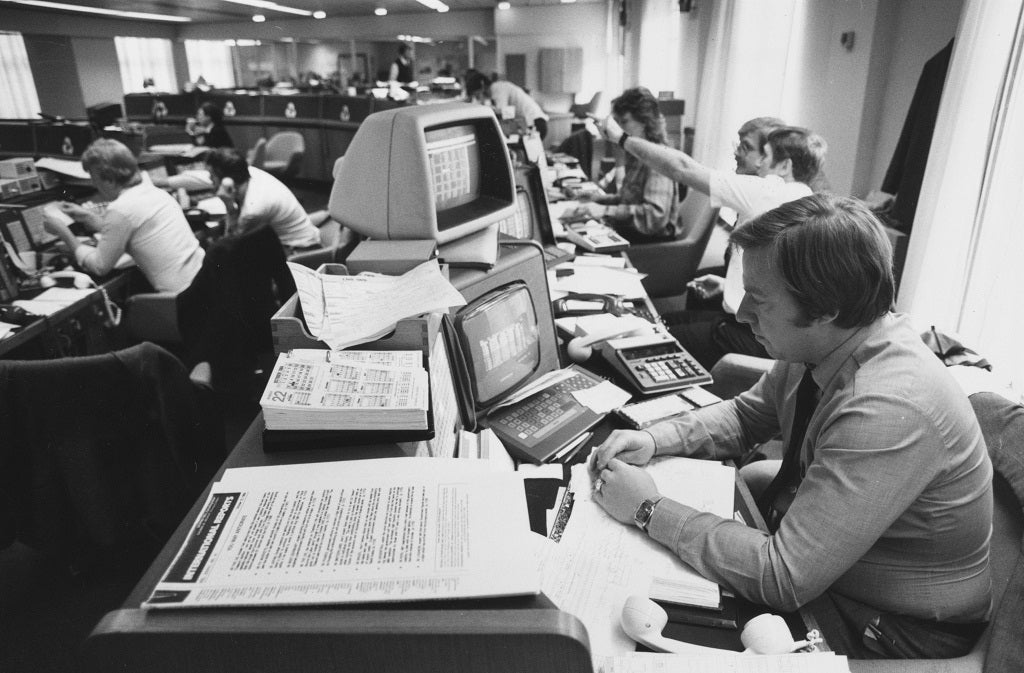

The banks have, infamously, led the way, in their greed and arrogance. But it is easy to forget the income band that falls just below them. They are everywhere to be seen in the private and public sector – what in old parlance used to be called white-collar workers.

The furore over the BBC’s severance payments to George Entwistle has highlighted the absurdity of contemporary employment contracts, behind which Lord Patten has hidden in seeking to explain the payout to his defenestrated Director-General. The BBC’s indulgence of its senior executives has long been indecent, but it merely reflects a broader national trend.

The assumptions that underlie these contracts are easy to unpick. First, that old canard: “only the best”. This phrase is cited for chief executives of local authorities and heads of quangos paid salaries in many hundreds of thousands. Some may be excellent, turning around ailing institutions, injecting financial rigour and motivating staff. For each one of those, there are at least as many who have risen without trace and will disappear without trace.

At the BBC, one of the perennial tensions is the mismatch between those in creative and journalistic positions – often people of fierce intelligence and industriousness – and managers of far less talent with feather-bedded terms and conditions. When Mark Thompson, the former DG, used to wax lyrical that he and his mates were paid silly money because “we’re worth it”, the mirth was mixed with anger. The idea that the BBC, or a local authority, could not find someone at least as good on half the salary has never stood up to scrutiny.

A second assumption is that if these poor mites have to be “let go”, they must be sent on their way in style. Again, it comes down to the contracts, which can stipulate a year or more’s salary even after a few weeks in the job.

This is based on a dual illogicality. “Compromise agreements” – the means by which someone can be eased out, technically by mutual agreement – take into account the period of unemployment that person is expected to face before they find a new perch. But either a senior manager is talented, in which case they are likely to get back on their feet quickly, or they are not, in which case the question arises: why were they given a top position to begin with?

There is perhaps only one reason for an extended payout (apart from unfair dismissal): if someone in high position is required to take “gardening leave” in order to preserve governmental propriety or commercial confidentiality. Other than that, a few months’ salary should suffice to tide them over while they reacquaint themselves with the headhunters.

In a bid to inject dynamism and growth into the sluggish economy, the Coalition has been directing its frustration at the UK’s employment laws in the wrong direction. The report last year by Adrian Beecroft, a venture capitalist and Conservative party donor, recommended a “fire-at-will” policy.

It was mercifully given short shrift by Vince Cable, the Business Secretary, but the Tory side of the Government has come back for more. First of all, George Osborne proposed a “shares-for-rights” scheme. In exchange for a tiny amount of equity, employees would happily waive their rights to employment protection, flexible working, time off for training and more. That, for the moment, has been seen off. Ministers have, however, settled on a plan to reduce the consultation period for large-scale redundancies from 90 to 45 days.

In all levels of the workplace, it is easy to identify poor performance. Anyone who has managed a team can identify the “I need to take the morning off because my cat has an ingrowing toenail” employee. (I jest only slightly.) It is quite hard, particularly in small organisations, to shift people like these without incurring cost. It is usually easier to keep them there, knowing that no matter how hard you try to improve performance, they are unlikely to get much better and they will never leave voluntarily – because they know they will struggle to find anything else.

The same goes for the top echelons, too. Some of the “lifers” at the BBC would not survive long in the tough world outside. When they fail – as we have seen many do in this week’s Pollard report – they get reinstated or moved along to another cushy number. The same goes for CEOs and others in the public and private sectors.

The reward-for-failure culture is deeply embedded in British society; but it is at its worst at the top. It is here that Cameron should focus his reformist, and punitive, zeal.

John Kampfner is author of 'Freedom For Sale'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments