Bush whack: How to turn poachers into gamekeepers

Kapuna Lepele made a relative fortune killing elephants for their ivory until 300 villagers made him change his ways

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For 11 years Kapuna Lepele was a poacher. He and his fellow elephant killers would spend weeks in the Kenyan bush tracking the animals before harvesting them for their ivory. His favourite method was to wait by a watering hole, hiding behind a nearby rock, before firing a poisoned arrow as they came down to drink. In total he killed 72 elephants that way.

Compared to the profits made by the criminal overlords he answered to, the rewards were not great. They can command £1,400 per kilogram for tusk sold on the black market to ivory-hungry clients in Asia. Lepele would only receive a few hundred dollars for a successful hunt.

But that was enough to make him a rich man in an area of East Africa where most people struggle to earn as much as £3 a day. He would have been able to buy a house not only for himself but for his parents, as well as luxuries far beyond the means of most of his peers.

The problem was he could not spend it. The local people in the surrounding area were so outraged by his activity they banned him from their villagers, forcing him to sleep in the forest. “At one point 300 members of the local community came to find me to tell me stop,” he said. “They were saying you are a notorious poacher. I knew I was not welcome.”

It is this local pressure that forced him to give up his trade; indeed resulted in the now 39-year-old using his knowledge of the illegal activity, and understanding of the local elephant herds, to help the wildlife cause by becoming a member of the anti-poaching teams at Laikipia’s Lewa conservancy.

“I was wrong to do what I did,” he now admits. “Protecting the animals not only gives me a job so I can feed myself but it also brings money into the whole area, meaning we can feed the community.”

One of the greatest achievements by the charity adopted as the subject of this year’s Independent Christmas campaign, Space for Giants, has been its work with local people in East Africa to persuade them of the advantages that can be reaped by joining the conservation cause.

What I had not previously realised was how separate much of Africa’s remaining wildlife is from the vast majority of people who live there. Increasingly limited to living in highly-protected areas, the animals are often hidden behind electric fences.

This means that the animals have never been seen in the wild by most Africans. As a result they can be perceived as for rich tourists rather than for the local people. It is why community outreach – along with establishing a new conservancy, supporting anti-poaching rangers and developing a better understanding of elephant herds’ movements through GP S tracking – is one of the key areas to which funds raised by Independent readers will be targeted.

Space for Giants and its partners, particularly the Northern Rangelands Trust, have instigated a range of programmes to help rural communities establish their own conservancies so they can live alongside and reap the economic benefits of wildlife.

Educational programmes also visit settlements to explain how conservation – and the money it attracts – helps them. Activities such as this have resulted in poachers being ostracised by those they had lived alongside.

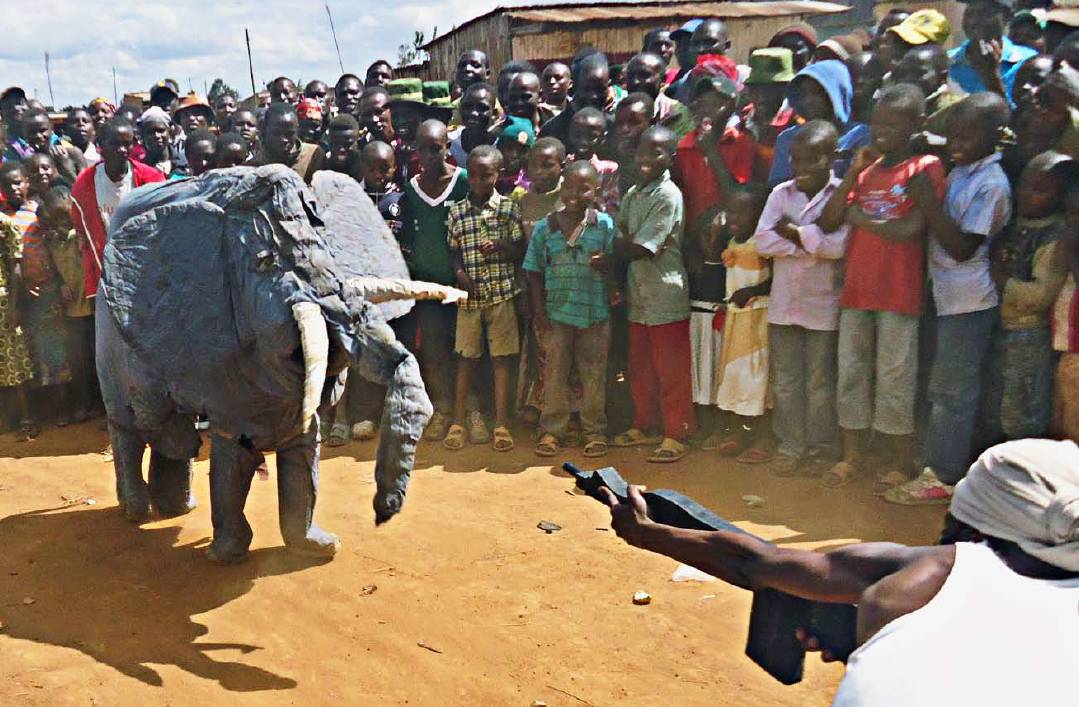

Outside a simple café that stands deep in the bush, I watched a performance of a play by one of the drama groups Space for Giants funds to tour local areas.

The story told of a husband who had resorted to poaching to pay his drinking and gambling debts. Many of his neighbours, who feared how it would threaten the tourist trade and the local schools and health clinics it helped finance, were horrified.

The groups’ theatrical director, Mutugi Kevin Magambo, said: “If you are playing a poacher there might be poachers in the audience. If you are playing a farmer, most likely there are several farmers in the audience. The responses and impact we have had from individuals and communities have been life changing.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments