Bought off: how crime fiction lost the plot

Thriller writing was once a British strength, but publishers are reducing it to a formulaic genre. Time, maybe, for murder most foul...

The British Library's new exhibition is Murder in the Library: An A-Z of Crime Fiction. Perhaps it will give readers a chance to discover the dazzling range of crime fiction available, and encourage them to step away from publishers' current offerings, because, at the present time, the genre has backed itself into a dead end.

Let me explain. Some years ago, I was in a Soho taxi late at night when its driver was attacked by two businessmen. I agreed to act as his witness, but outside the courtroom the police persuaded the plaintiff to drop his case in exchange for cash. The driver had shouted at the men, who were drunk, and court proceedings would only cause everyone more trouble. It was a reasonable solution, if an unexciting one.

If you've ever been the victim of a crime, you'll know that it's a very different experience from its fictional equivalent. Police stations are like hospitals; most of what goes on is behind the scenes. The rest is just waiting around and trying to reconcile your anger and frustration with the orderly procedures you have to face. If crime fiction accurately reflected this, it would be moribund.

Yet publishers are keen to convince us that their latest murder mysteries are grittily realistic. They are not, but, more to the point, they never were and never will be. How many killers are captured while they're still in the middle of their slaughter sprees? How many have ever planned a series of murders according to biblical arcana? How many leave abstract clues for detectives and get caught just as they're about to strike again?

Crime fiction is a construct, a device for torquing tension, withholding information and springing surprises. Yet every month dozens of crime novels appear that promise us new levels of realism, when they patently supply the reverse. We'll happily believe that the murder rate in Morse's Oxford equals that of Mexico City if the story is told with conviction.

The latest census data about Britain is revealing. The number of people with no religion has risen to 25 per cent, the white population is down to 86 per cent, one in every three Londoners is born abroad, the Muslim population is nearly 5 per cent, gay marriage has Tory approval and one very proud Sikh guardsman just wore his turban instead of a bearskin for the first time. It's clear the country is changing fast, and economic mobility is a major catalyst.

However, there is a part of England that forever has an alcoholic middle-aged copper with a dead wife, investigating a murdered girl who turns out to be an Eastern European sex worker. This idea might have surprised a decade ago, but it's sold to us with monotonous regularity. It's not gritty, it's a cliché.

Lately, there have been some terrific thrillers from Irish and Scottish authors that genuinely reflect the changing nation, but very few are set in the supposed nexus of all this transformation – London. Crime fiction accounts for more than a third of all fiction published in English, but in my review pile for the spring there are hardly any contemporary London stories. The most audacious new crime novel I've read lately is Gun Machine by Warren Ellis, who lives in Southend, but his book is set in Manhattan. More novels in translation are being published, plus a hefty stack from America, but many of their British equivalents are set in the past and nearly all are devoid of humour.

This is odd, because black comedy is something we do very well, from The Ladykillers to Kill List. Now, though, very few crime writers dare to stray from the narrow path set by publishers in the wake of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. Stieg Larsson's books are proof that you can get away with anything if you say it with a straight face. They're enjoyable reads, but patently ridiculous. The Killing was excellent television, but its success has only exacerbated the problem for authors. As Tony Hancock once said, "People respect you more when you don't get laughs". We are told that readers want veracity, but readers will accept that a murderer is stalking London according to the rules of a Victorian tontine, even though they'll ask why your detective doesn't age in real time. Consequently, there's an accepted format for crime fiction that has become even more constricted of late, from subject matter to cover design, until it's almost impossible to tell one author from the next.

It wasn't always like this. Golden Age mysteries frequently featured absurd, surreal crimes investigated by wonderfully eccentric sleuths. From Gladys Mitchell and Margery Allingham in the Thirties to Peter Van Greenaway and Peter Dickinson in the Sixties, the form was treated as something joyous and playful. The Notting Hill Mystery, which many regard as the first detective novel, was recently republished by the British Library and consisted of letters, reports, floor plans and notes. Dennis Wheatley created a similar set of whodunnits and added a dossier of photographs, blood-stained material, a burned match, a lock of hair and other pieces of evidence in little bags.

Allingham regarded the crime novel as a box with four sides; "a killing, a mystery, an enquiry and a conclusion with an element of satisfaction in it". Her plan, which I think is as good a template as any, was to reduce books like stock: to boil them to a kind of thick broth of language that tasted rich enough to satisfy and left you wanting to copy down the recipe. To continue the culinary analogy, she believed in the "plum pudding principle", whereby you provide your readers with a plum every few bites, to keep them interested.

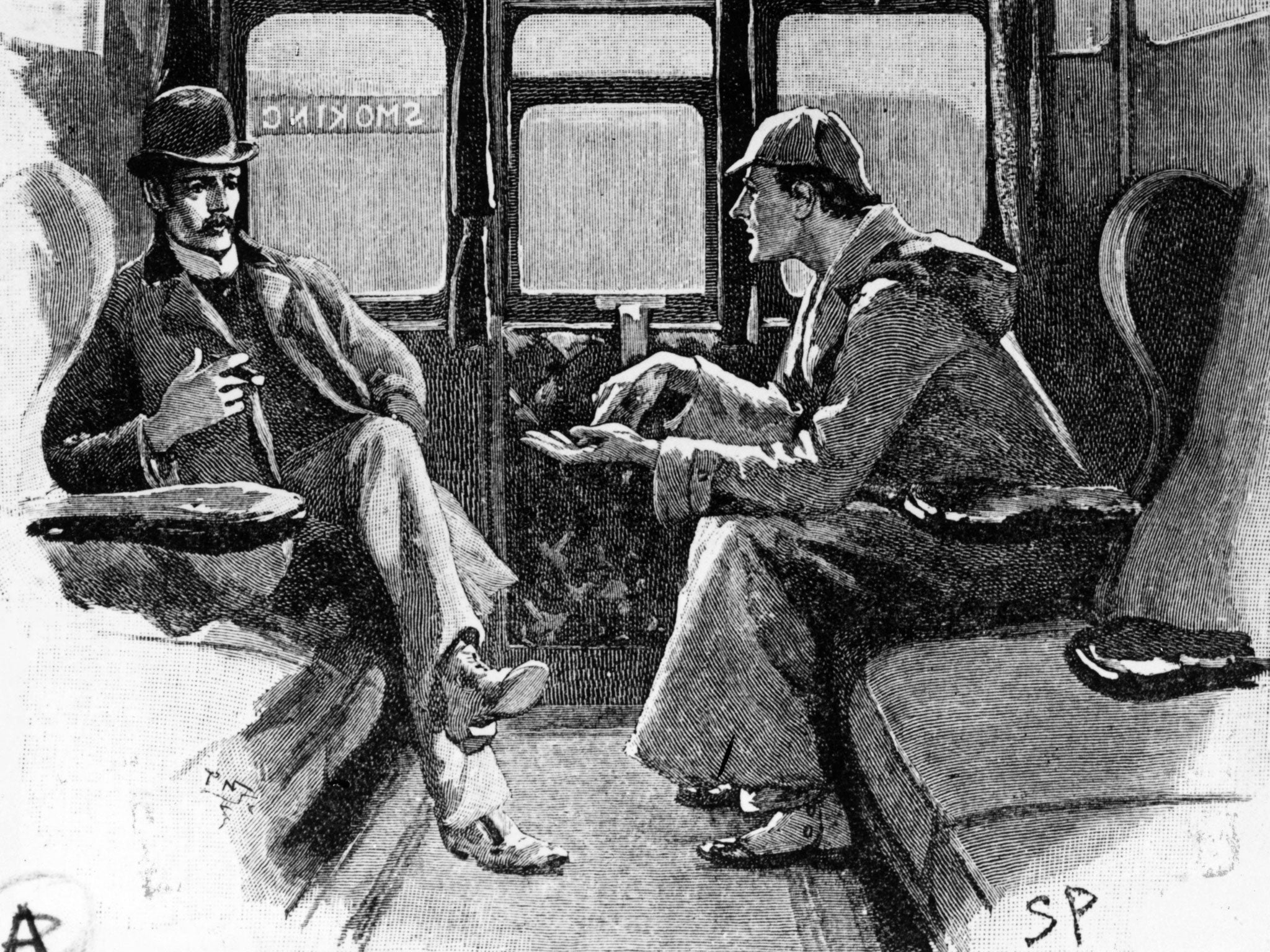

Now we get doorstops of unrelenting grimness. A handful of characters have become brands, such as Sherlock Holmes, Bond, Dracula and Batman, and every year delivers another crate of old wine in new bottles. Kim Newman, whose own excellent Holmes books far exceed the quality of the current TV reinvention, has pointed out that TV doesn't need to purchase new ideas so long as it can get away with stealing old ones.

The Sherlock Holmes adventures had little veracity. Men went raving mad in locked rooms, or died of fright for no discernible reason. Women were simply unknowable. And even when you found out how it was done or who did it, what kind of lunatic would choose to kill someone by sending a rare Indian snake down a bell-pull? Who in their right mind would come up with the idea of hiring a ginger-haired man to copy out books in order to provide cover for a robbery?

We still enjoy Hercule Poirot because, like Holmes, he ushers us into a lost world of colonels, housemaids, vicars, flighty debutantes and dowager duchesses. But, at the time they were written, surely nobody found them realistic. At least Conan Doyle's solutions possessed a strange plausibility, whereas Christie's murder victims apparently received dozens of visitors moments before they died, with their murderous pots of jam, guns attached to bits of string, poisoned trifles and knives on springs.

As the author of the Bryant & May novels, a series featuring a pair of argumentative elderly sleuths, I'm placed on crime panels with other dissident writers such as Ben Aaronovitch and Charles Stross, because we're prepared to present ideas rather than pursuing false credibility. There are so many other crime stories to tell, farcical, tragic, contemporary and strange. It's time readers were allowed to discover them.

Christopher Fowler is an award-winning author. His books include '10 Bryant & May mysteries'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks