Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

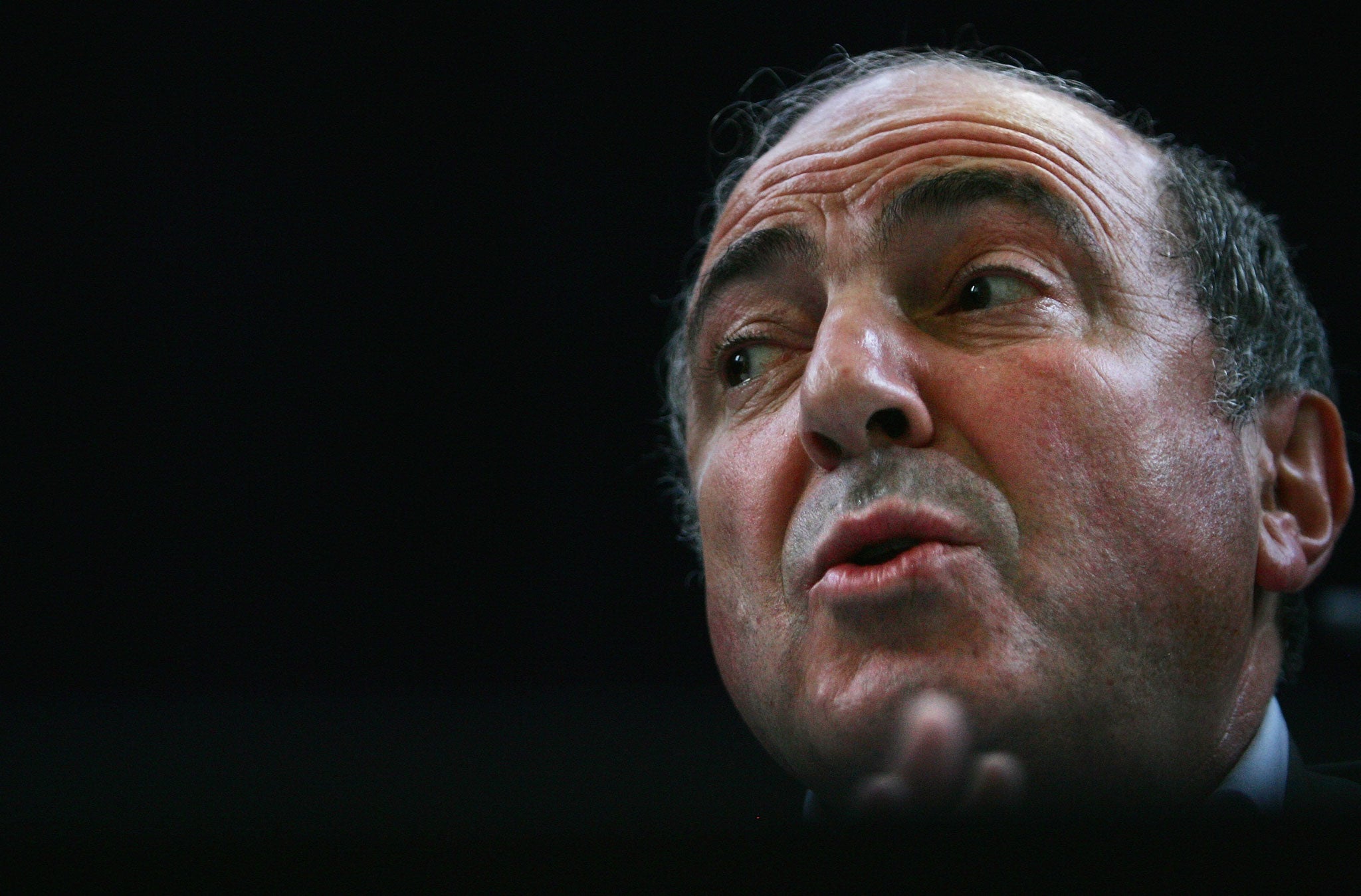

Your support makes all the difference.For the paparazzi that hung around outside London’s High Court almost every day in the last four months of 2011, the blinking unshaven face of Roman Abramovich was the picture that paid the bills. But inside, there could be no mistaking who was the central figure in a simply jaw dropping six billion dollar drama.

It seemed inconceivable, as we sat and listened to tale after tale from of the life and times of one of the most remarkable men of this or any era, that Boris Berezovsky hadn’t already received the Hollywood treatment. This stuff was Goodfellas on crystal meth.

Alright, so it wouldn’t be a cheap movie to finance, with the private planes, the yachts, the football clubs, the chateaus on the French Riviera, the giant aluminium smelters in Russia’s frozen east. Then there was the crashed helicopter, the stricken submarine, the car bomb that decapitated his driver but left the man himself unscathed. The world’s finest hotel rooms would have to be booked, the palatial Kensington homes, the glamorous women, and the suitcases stuffed with cash. All these things cost money.

Someone would have to be brave enough to write it too. Order a few of the leading books on the world of Boris Berezovsky and you’ll find a few of the authors have come to a premature end.

But the most insurmountable obstacle is how on earth to make the movie make sense. Every character, even in a true story, has to have a dramatic purpose. Something he must either succeed or fail in achieving, be it to escape from Shawshank Prison, to phone home or to get rich or die trying.

Taking flight

Attempting to understand the motivations and machinations that whirred inside the cannon-ball head of a mathematics professor, turned car salesman, turned politician, turned outspoken activist and bankroller of revolutions is a near impossible task. It is, to paraphrase Churchill, a riddle, wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

But what is the key? It is not, unlike Roman Abramovich, to be found in merely the ruthless accumulation of wealth, and the extravagant spending of it - though Berezovsky displayed more than a little aptitude for both.

Having spent the seventies and eighties publishing papers on mathematical processes, he emerged from the collapse of communism as his nation’s pre-eminent capitalist. When the Berlin wall fell in 1989, Vladimir Putin was in Dresden, shredding KGB documents and desperately telephoning Moscow but no one was answering. Roman Abramovich, a young Del Boy, was manufacturing plastic toys and selling them from his Moscow apartment. Berezovsky, along with his business partner Badri Patarkatsishvili, had hedged the effects of hyperinflation in their favour and amassed a great fortune buying and selling cars.

He set up a similar scheme while running the national airline Aeroflot. When his friend and business partner Nicolai Glushkov took to the witness box in London eighteen months ago, those present could scarcely believe what they were hearing as Abramovich’s barrister, Jonathan Sumption (who was himself collecting an £8m fee for the case) laid bare the details of a scheme in which a sizeable chunk of still-nationalised Aeroflot’s income was paid to a Swiss company owned by the pair. If payments came late the Swiss company charged a fee of several hundred per cent. The payments, surprise surprise, always came late. (Mr Glushkov, in his customary bow tie, denied the allegations).

Kremlin powerbroker

But for Boris, it was never merely about money. By 1995 he had moved into the media, convincing President Yeltsin to let him taking control of the country’s most watched television channel (and met Roman Abramovich, by now a young precociously-successful oil trader), which propelled him inevitably towards the intoxicating world of politics. It was in that year that the Big Bang deal was struck. A deal agreed, but never signed, in the almost comical surroundings of Boris Yeltsin’s Presidential Tennis Club, from which exploded the two men’s astronomical fortunes in the years to come. In return for support from Berezovsky’s television channel in the 1996 Presidential election, Yeltsin agreed to auction off vast state oil assets. Thatcher’s PR man Tim Bell was flown in, Yeltsin won the election. Berezovsky and Abramovich connived to buy the assets for around £60m. Ten years later, with Berezovsky outmanoeuvred and languishing in exile in the UK, Abramovich sold the assets back to the state for an eye-watering £7.5bn. This was the cash at the heart of the court battle.

Having tasted immortality in the Kremlin, Berezovsky had apparently shown little interest in the running of the business. But he was not immortal. He was the central powerbroker of the Kremlin era, but the man he found to replace him, the then-Mayor of St Petersburg Vladimir Putin, proved not to be so malleable. Putin rightly sensed that the public didn’t like this new family of oligarchs, who had moved quickly to pillage the nation’s assets when one state collapsed and before another could be built around them. When he threatened them, Berezovsky fought back, using his television channel to interview the distraught wives of the sailors trapped on the stricken Kursk submarine, heavily criticising Putin’s handling of a disaster attracting international attention. His friends warned him to stop. He didn’t. And eventually he fled, first to Paris then to London, and never went back.

It wasn’t as much the mutations the Russian state went under in the years that followed that so tortured him, it was that he was no longer at the centre of things. Under the guise of a pro-democracy campaigner he attacked Putin’s Russia at every opportunity, and spent unimaginable fortunes funding political campaigns in Ukraine, and Chechnya. Winning the Champion’s League might appear expensive, especially given the number of managers it took Roman Abramovich to do it, but when compared to winning an election, bringing down a government or ending a war. Well.

Discredited

Putin’s Russia is undoubtedly a questionable place. The secret police expanding at the expense of democracy, armfuls of ballot papers secretly filmed being shoved into ballot boxes, and journalists murdered on their doorsteps. But had Berezovsky not made the fundamental error of underestimating him, and had he remained stalking the corridors of the Kremlin, would his protests be so loud? Would the situation be so wildly different? We can never know.

Those who moved to dismiss the idea that he had taken his life as that story emerged in the immediate aftermath of his death, pointed at the upcoming inquest, in London in October, of his friend Alexander Litvinenko, the former KGB spy poisoned at a London restaurant in 2006. The world, and Putin, will again be watching then, and Berezovsky would, they say, have relished his chance to again attack his nemesis on the world stage.

But that, probably, is to misunderstand the man. When Lady Justice Gloster summoned us all back, seven months later, to that neon strip-lit room down the road from St Paul’s Cathedral, she could not have been more damning. Abramovich, she said, had been a reliable and honest witness. Berezovsky on the other hand had been “deliberately dishonest”. He was an “unimpressive, and inherently unreliable, witness, who regarded truth as a transitory, flexible concept, which could be moulded to suit his current purposes.” They were words he would never be able to shake off. They also meant he was broke. He would never be able to force himself back to the centre of things. He may even, we hear, have written to Putin asking for forgiveness.

Roman Abramovich didn’t even turn up to court that day. The flash bulbs and the cameras outside were Boris’s alone, but Berezovsky: The Movie was over. Whether the final scenes turn out to have been foul play, suicide or natural causes, they were the nevertheless the denouement of a broken man.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments