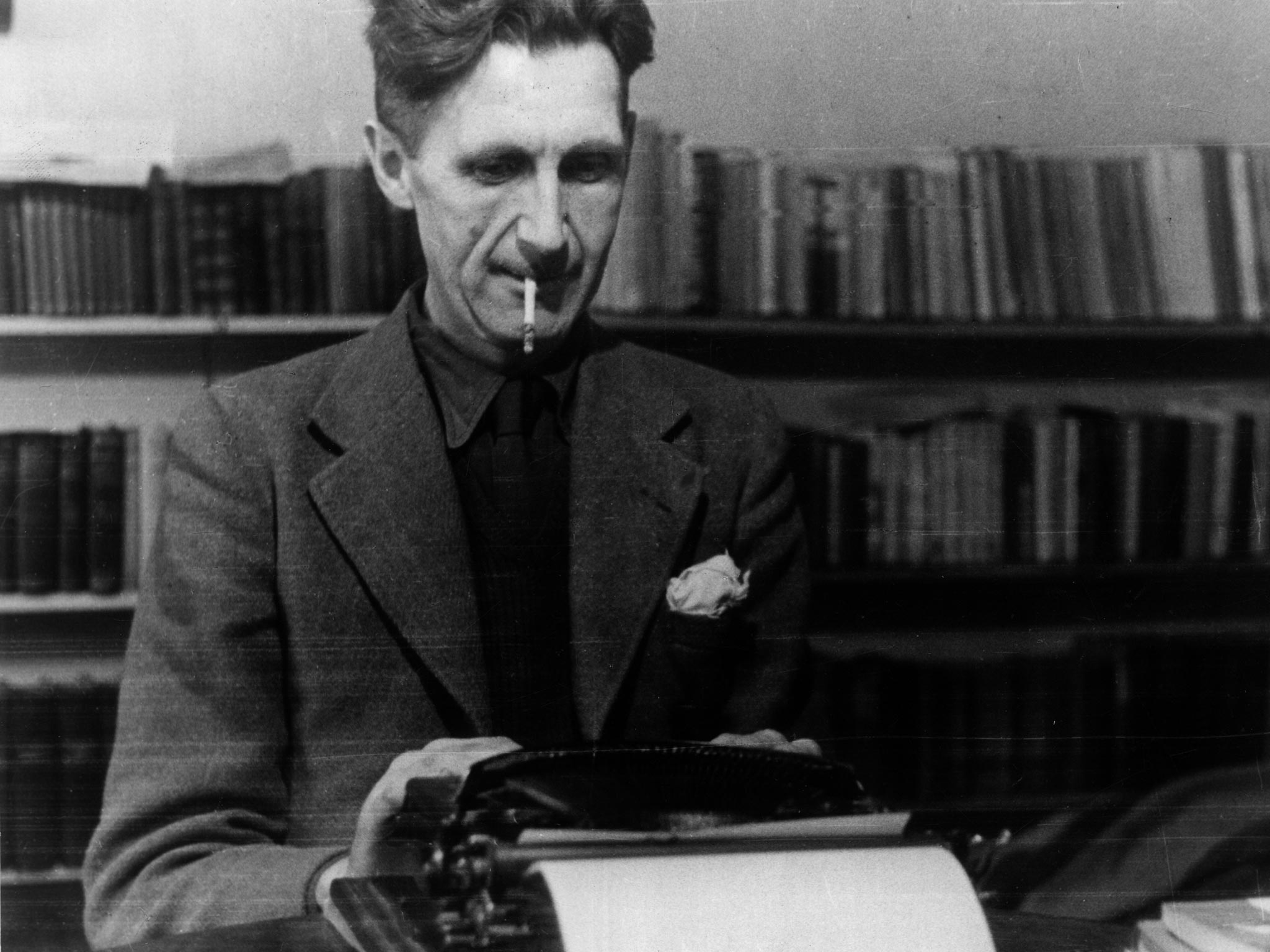

Avert your eyes, George. The Orwell Prize has become an establishment love-in

Here are just a few of the radical writers left off the longlist

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Three days after the death of Margaret Thatcher, former Lib Dem leader Sir Menzies Campbell accused his fellow Question Time guest, Thatcher biographer Charles Moore, of exhibiting “a persecution complex that is quite unjustified”. Moore had slated the BBC for promoting the idea that Thatcher was “divisive”.

Last week, Moore was longlisted for the Orwell Prize – probably Britain’s most prestigious award for political writing. “Every year,” the organisers say, “we award prizes for the work which comes closest to George Orwell’s ambition ‘to make political writing into an art’.” Along with Moore’s Thatcher book, nominees for this year’s book category include Tory MP Jesse Norman’s Edmund Burke, Simon Sebag Montefiore’s new novel and former cabinet minister Alan Johnson’s “childhood memoir”. No doubt they’re all written in exemplary prose. But Orwell would have cutting words about a prize for daring polemic heaping laurels on establishment figures who write about fashionable establishment subjects.

If anyone recognised that artful political writing was not simply writing well about politics, it was Orwell. “Any writer or journalist who wants to retain his integrity finds himself thwarted by the general drift of society rather than by active persecution,” he wrote in 1946. The revivalist hymn “Dare to be a Daniel / Dare to stand alone”, he said, could be updated with a “Don’t” at the start of each line.

Orwell knew the price of going against the grain: he found himself a pariah on the left for his criticism of Stalin, and subsequently struggled to find a publisher for Animal Farm. 64 years after his death, being a Daniel in political writing still pushes one to the margins. It’s hard enough getting a publisher to pay attention if you’re not already prolific, but say the unsayable and your chances are all but scuppered. Orwell blamed “the concentration of the press in the hands of a few rich men, the grip of monopoly on radio and the films, the unwillingness of the public to spend money on books…” Add to that publishers’ increasing reluctance to pick up either literary fiction or any non-fiction that isn’t “as seen on TV” or infatuated biography. Perhaps a prize for political writing could give those who dare move against this some much needed cash and publicity.

An obvious candidate from this year’s nominees is Robin Bunce and Paul Field’s “political biography” of the activist and journalist Darcus Howe. The book is political in far more than its content: as the authors rightly say, Britain’s Black Power movement is in danger of being written out of history. True, Bloomsbury has so far given it a limited print-run and a high cover price. But if the Orwell Prize had not capitulated to establishment back-scratching and fashionable publishing trends, perhaps books like this could reach the wider audience they were written for.

Undercover, by Rob Evans and Paul Lewis, is a remarkable expose of police infiltration of activist groups. In The State We Need, Michael Meacher has penned a thorough and astute riposte to the austerity consensus dominating all mainstream political parties. The rules allow political pamphlets too, so why not consider Carol Turner’s powerful short biography of Walter Wolfgang? It truly challenges the accepted wisdom that ordinary citizens are irrelevant to our political ongoings. Instead, the judges have gone for a safety-first longlist. Their chosen books will have been in shop windows anyway.

It hasn’t always been this way. The longlists for the book and journalism categories have always been biased towards establishment figures, but in 2009 the Prize took the innovative step of introducing a blog category. First awarded to NightJack police blogger Richard Horton, for four years the blog prize gave mainstream prominence to online writing that was truly politically challenging. When the category was withdrawn for the 2013 cycle, prize director Jean Seaton wrote that blogs had "been subsumed into the mainstream", and could now be nominated for the journalism category. What a shame that the only journalist from outside the mainstream print commentariat on this year’s longlist is Exaro’s David Hencke, formerly an established Guardian reporter. Hencke and others on the list have produced sterling work, but eleven of the fifteen are white men who already have a name for themselves. Would the likes of Sue Marsh, author of hit blog Diary of a Benefit Scrounger get a fair hearing? Where is Priyamvada Gopal, whose originally-angled freelance contributions to a number of platforms have sparked discussion on everything from Valentine’s day to Ralph Miliband’s patriotism?

Some will say that this year’s judges can’t help it if a certain dinner party circuit are more likely to self-nominate. But prize organisers urge the public to “get in touch” if they feel someone is worthy of the accolade so they clearly take a pro-active role in the nominations. It’s time for them to think about whether their task to reward writing that is truly admirable for its political dare, or to promote the sort of infatuation and self-importance that Orwell loathed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments