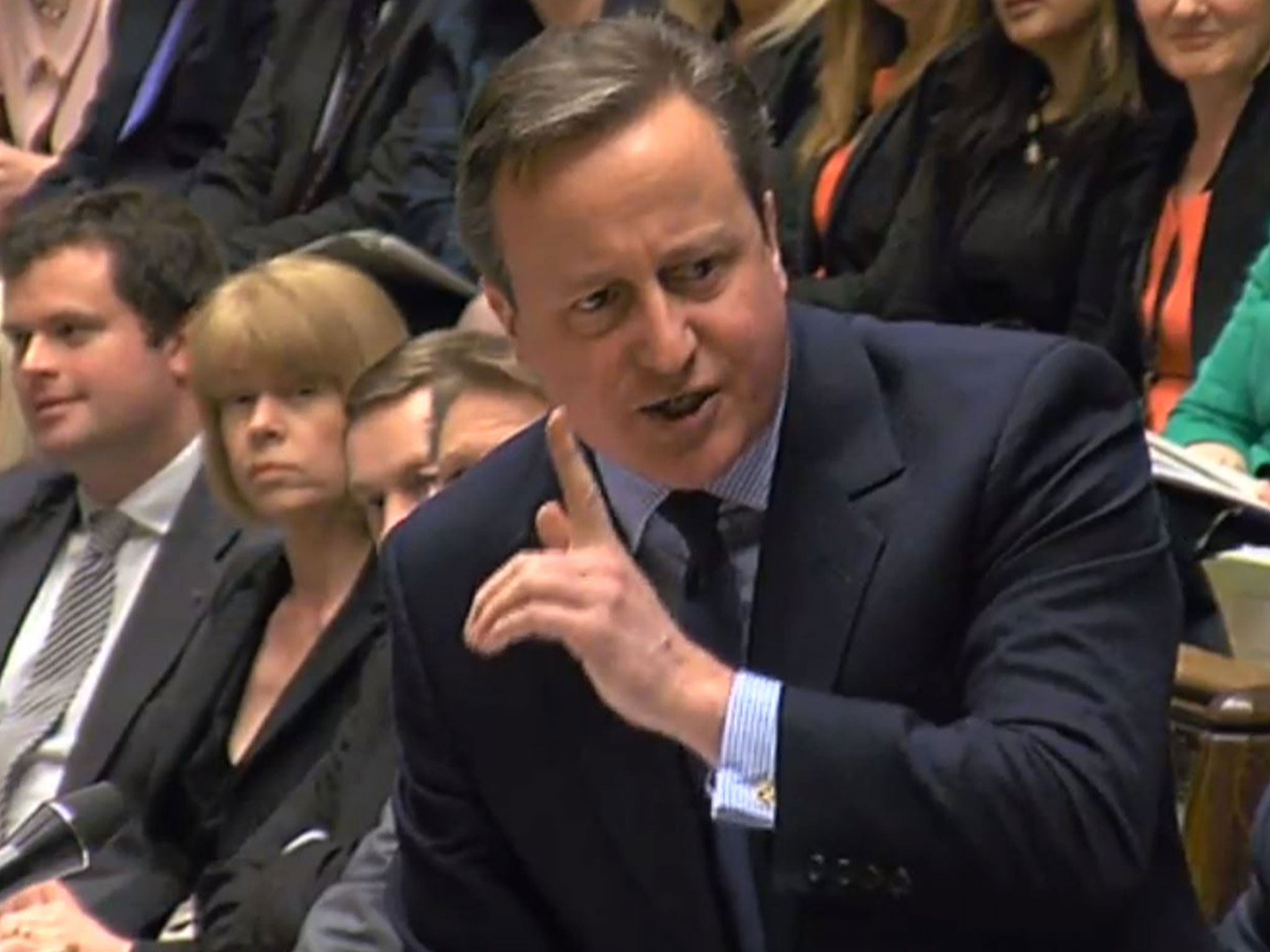

At PMQs, Cameron answered Corbyn's questions - but not in the right order

The Prime Minister subtly undermined the Labour leader's 100th question by answering his 99th – and by answering it rather well

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was a bit of gimmicky spin from the Labour leader who is supposed to be doing the straight-talking, honest politics, but the device of asking his 100th question at Prime Minister's Questions was an effective one. "My previous 99 attempts have left me unclear or dissatisfied," said Jeremy Corbyn, as he prepared to ask his fourth of today's session.

So for this special question, he reverted to his signature tactic of reading out an email from a voter. In this case Calum, "a bright young man" who wanted the Government to acknowledge the importance of sixth-form colleges and post-16 education. That was such a soft question for David Cameron that he avoided the obvious answer, "Absolutely, it is very important," and sitting down.

Instead the Prime Minister made use of a parliamentary convention that he has deployed before, of answering the leader of the opposition's previous question, which was about child poverty. Thus he responded to Corbyn's 100th question by answering his 99th: a most subtle way of undermining the significance of Corbyn's round number.

Or perhaps it was a tribute to the testing quality of Corbyn's 99th question. Cameron had waffled in answer to the accusation that there were another half-million children living in poverty, saying the Budget was next week and there were fewer workless households under this government. It wasn't until he had sat down, and while Corbyn was asking his rather long centenary question, that the Prime Minister was briefed on the child poverty figures.

As well as solemnly declaiming on the importance of colleges of further education and giving the single transferable answer about apprentices, therefore, Cameron went back to the previous question and answered it properly. There are 300,000 fewer children in relative poverty than in 2010, he said. This is true, and it is surprising that Corbyn appears not to know the figures. The first rule of asking a question in politics is to know the answer.

As Cameron also pointed out, relative poverty is the definition preferred by the Labour government: the official poverty line was 60 per cent of median income until Iain Duncan Smith came along and abolished it. He shouldn't really have mentioned that bit, because it draws attention to his Government's attempt to abolish poverty by redefining it, while at the same time trying to take credit for reducing poverty on Labour's own preferred measure.

Corbyn had – in his 99th question, not his 100th – almost hit on a line that might have embarrassed the Prime Minister. After misquoting child poverty statistics he ended with a rhetorical flourish asking Cameron to ensure that the "further reductions" in public spending of which the Chancellor has warned should not fall on pensioners, children and women.

If only his great round-number question had been a forensic one about the effect of planned spending cuts for the rest of this parliament, which are – unlike the last, Lib-Dem-influenced parliament – planned to fall on the poor.

Instead it was Calum and his sixth-form colleges, followed by a couple of questions about housebuilding, the construction industry and a "recovery constructed on sand" (no, really). That allowed Cameron to quote selective statistics about housebuilding starts being at their highest since 2007.

Still, at least Corbyn's questions weren't as stupid as one asked by one of his few supporters on the Labour benches, Richard Burgon, the shadow City minister. He asked if the Prime Minister could give a straight answer to a straight question. "If the British people vote to the leave the EU, will he resign as Prime Minister, yes or no?"

Cameron gave him a straight answer: "No."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments