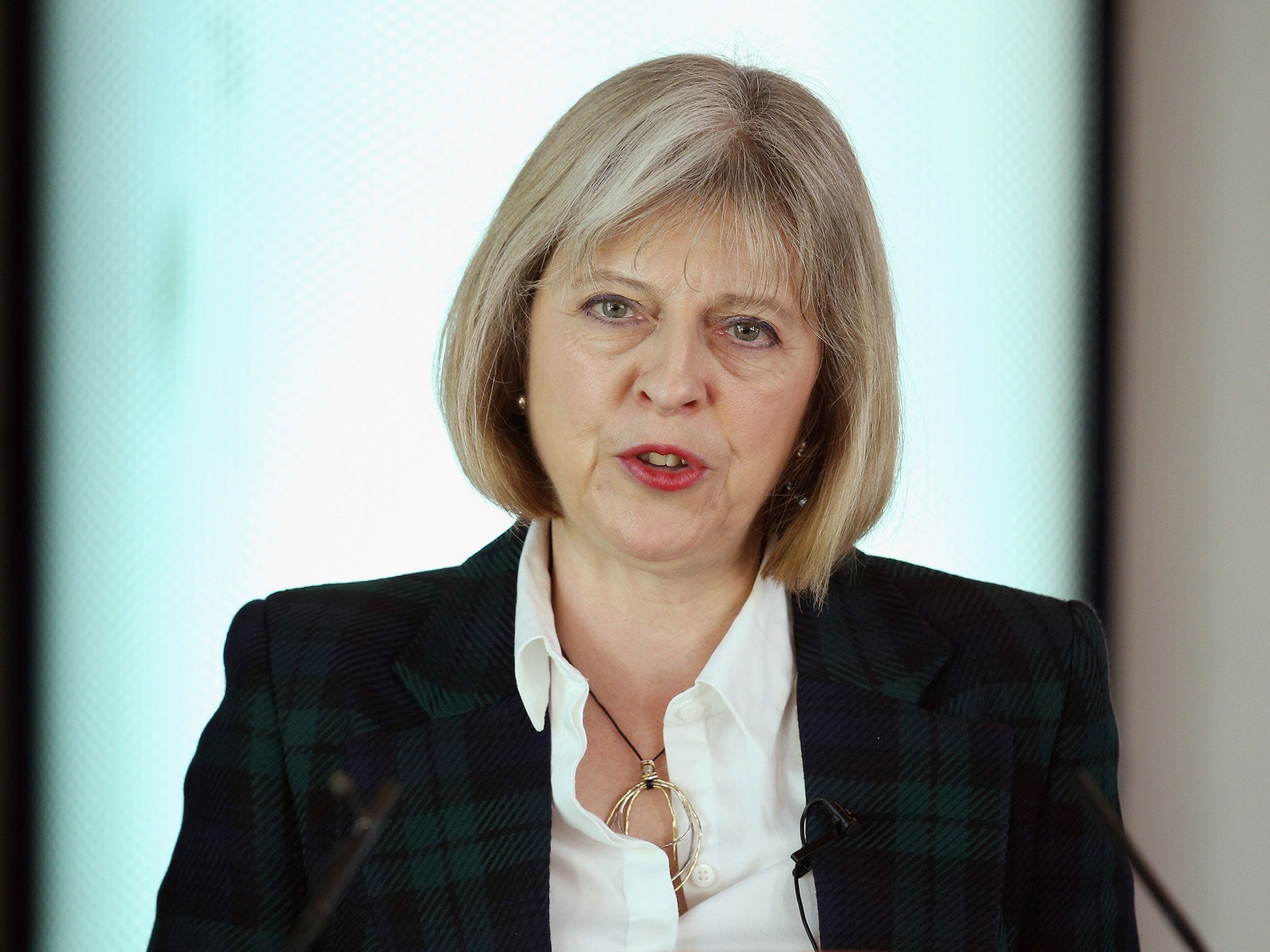

After the debacle of the child abuse inquiry, Theresa May is turning to a new type of politics

The Home Secretary has demonstrated a very rare quality among Conservative ministers – empathy and bipartisanship

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At last I see signs of a new way of doing politics. You may be surprised at the counter-intuitive nature of my two examples, Theresa May, the Home Secretary, and Nicolas Sarkozy, the former French President who is seeking to reverse his recent defeat.

To start with May, I was astonished at the nature of her statement in the House of Commons on Monday explaining how she intended to proceed in finding a chair for the inquiry into historical child abuse. For by setting out a thorough process of consultation, the Home Secretary embraced participative decision-making.

She said that she herself would hold meetings with representatives of the survivors of child abuse. Hitherto the survivors’ leaders have met only officials. She will also discuss the appointment of the new panel chair with the shadow Home Secretary.

I don’t know whether this has happened before but securing what would be in effect a bipartisan appointment would give strength to the new chair and to the inquiry. Moreover, May said that she would consult Keith Vaz, the chair of the Home Affairs Select Committee that rightly gave a hard time to Fiona Woolf, whom the Home Secretary had previously selected.

In addition, the Home Secretary said that what she called the “nominated” panel chair would attend “a pre-confirmation hearing before the Home Affairs Select Committee”. “Nominated” I take to mean “proposed” rather than “appointed”. All this comes close to giving the select committee a right of veto.

But this was not all. Widening out the scope for participative working, May said that the panel secretariat was planning two regional events that will be held before Christmas and another four that will be held in the new year. “These regional events would provide an early opportunity for survivors to give their views about how the panel should go about its work,” she said.

Let us now leave the Home Secretary for a moment and enter the very different world of French political practice, albeit that French voters share the same despair with their political system that we do.

We should first note that French political parties of the right are readily created and disbanded as conditions change. There is nothing comparable to the British Conservative Party, whose origins go back to the 17th century. The present equivalent is the Union pour un Mouvement Populaire (UMP), founded by Jacques Chirac and Alain Juppé in 2002. Now Sarkozy proposes to dismantle it and create a new party.

The operation would be rather like the treatment of failing banks during the financial crisis – create a clean “good” bank and put all the embarrassing stuff into a separately owned “bad” bank. So what would be the characteristics of Sarkozy’s clean party? No longer would a Paris HQ impose policies on the regions by means of a vertical command structure. Party candidates for elections would be chosen through a system of primary ballots – in other words, members would choose rather than the party bosses. Finally policy would be made from the bottom up, with conventions established to study different issues and then reach a conclusion by a system of online voting. As Le Monde commented: “If this participative method were effectively applied, it would be a little revolution for a party of the right where the culture of the ‘chief’ has always dominated.”

Thus, for both May and Sarkozy, the new watchwords are decentralisation and participation. Let us test how this might work with the intractable problem of immigration. Imagine that once a year Parliament was asked to review and, if necessary, reset the regulations for admitting immigrants according to whether they were coming from European Union countries or non-EU countries. Crucially, this vote would be free, in the sense that MPs would cast their votes as they saw fit, not as their parties had instructed them.

But before this debate could take place, there would have been two prior events. Step one: individual MPs would have held consultative meetings in their constituencies. Quite apart from the nature of the discussions, the level of local interest would also convey a message. Step two: the relevant select committee would have held extensive hearings on the subject. Only then would come the free vote in the House of Commons. In this way would be combined decentralisation and participation. I cannot help thinking that by these means a lot of the hysteria that surrounds the immigration debate would be dissipated.

However, in her Commons statement, the Home Secretary went further. She demonstrated a very rare quality among Conservative ministers – empathy. In a break with parliamentary tradition, she said that she wanted to end her statement by speaking directly to survivors of child abuse. At that point, she was speaking not to the House but to the nation. She said: “I know you have experienced terrible things. I know we cannot imagine what that must be like.

And I know – perhaps because of the identity of your abusers or the way you were treated when you needed help – many of you have lost trust in the authorities. I know some of you have questioned the legitimacy of this process. I know you are disappointed that the panel has no chairman. I understand that. I am listening… We have a-once-in-a-generation opportunity to do something that is hugely important. Together, we can expose what has gone wrong in the past. We can prevent it going wrong in the future. We can make sure people who thought they were beyond the reach of the law face justice. We can do everything possible to save vulnerable young children from the appalling abuse that you suffered and endured” – a remarkably moving oration.

I have a feeling that in laying their plans, May and Sarkozy both started from the same place. They didn’t feel that they could any longer go on as before. They were in despair. The Home Secretary couldn’t go on choosing chairs for the child abuse inquiry who then withdrew because of unfavourable comment. The former French President couldn’t hope to win back the presidency in 2017 with a party that had misappropriated funds and was riven by civil war. So they started again and were irresistibly drawn to what I believe will be seen to be the three rules of what I will call the new politics –decentralisation, participation and empathy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments