A remarkable episode of Panorama on people with severe head injuries showed the BBC at its best

The programme raised ethical quandaries on the meaning of consciousness and consent, and showed how much we still have to learn about those who are "locked in"

Last night’s Panorama was an example of what the BBC can do when it puts its mind to it, but too rarely does.

In case you didn’t see it (and I’d urge you to watch it on the iPlayer) the programme looked at victims of severe head injury, so severe that they are classified as being in a “vegetative state”.

Except, that thanks to the pioneering work featured, it has been found that some of these people, about one in five, should not be classified thus. This group of patients may actually be aware, and conscious for differing periods, but are effectively “locked in” to bodies they cannot control.

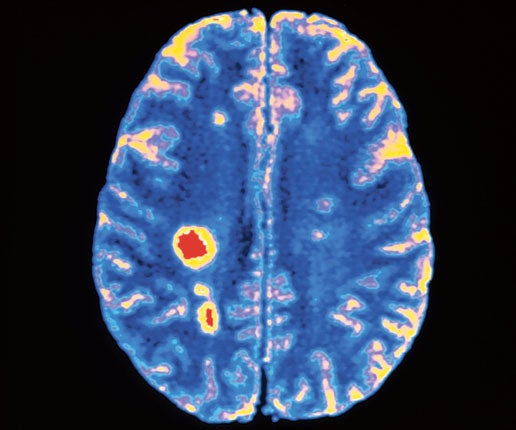

The scientists and medics featured in the programme have even been able to establish communication with some of them. Using a brain scanning machine they ask the patient to imagine playing tennis. If this results in blood flow to the relevant sectors of the brain (indicating they are complying with the instruction) they move on to asking them to imagine moving around their homes, which stimulates a different part of the brain.

They then asked one of the featured patients a question: If you are in pain imagine moving around your home. If you are not, imagine playing tennis. The relief on the faces of the parents of the man in the scanner when the “tennis” part of the brain was activated was palpable.

It was moving stuff and as well as featuring the families of those who found their horribly injured offspring were aware, it also showed a family who were told that their son probably wasn’t. Not everyone who participating was lucky enough to get good news.

A superb piece of film making then, the only downside being the irritating background piano music.

The programme also subtly raised some serious questions without either taking sides or ramming them down the throat of the viewer, as so many television producers do these days, treating their audiences as stupid.

The stinger came at the end: A number of “vegetative” - and I rather despise that term - patients in Britain have been allowed to die through the withdrawal of, for example, food and water.

What was not stated, and lingered in the mind after the film had ended, was this: What if some of those were among the group of patients who don’t appear to be aware but are. Just think about that for a moment. Were they, in fact, wrongfully killed; alive, aware, but unable to communicate their distress at being starved to death. Now how do we deal with that?

One of the programme’s subjects was a man who has made a miraculous recovery from a severe head trauma such that he is now able to move, and communicate by using a letter board (the patient painstakingly points at the letters on the board to spell out words).

He was able to describe what it felt like to be locked in - if my memory is correct he likened it to “screaming at a wall”. And yet his joy (and the filmmakers were there) at his release from hospital and return home was obvious.

Which raises another awkward question: What if some of those “locked in” patients wanted to end their torment by ending their lives, assuming the pioneers working on the scan technique can achieve a sufficient level of communication to ask the question. Would it be appropriate to ask? If there could be a chance of easing their suffering? Or if they could recover.

There are no easy answers. And there are no right answers. Perhaps we shouldn’t be seeking them so much as we should be asking more questions before taking decisions. Even decisions that appear to be “kind” and made with the best of intentions.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks