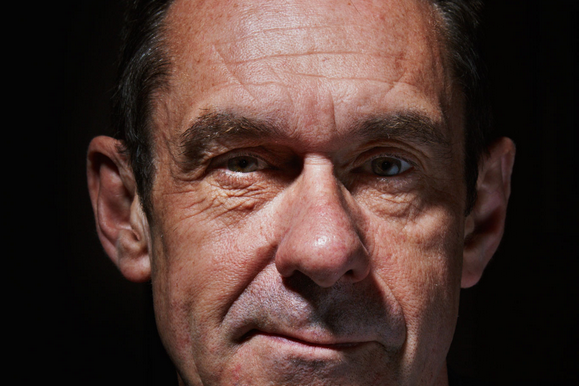

‘A Martian stranded on Earth’: more of the Paul Mason interview

Our chief political commentator went head to head with the author of Postcapitalism last Sunday: here is more of their conversation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I interviewed Paul Mason, economics editor of Channel 4 News, about his new book, Postcapitalism, for The Independent on Sunday last weekend. There was more in the interview than we had space for in the magazine, and it was all interesting, so here is more of it.

In the book Mason defines neoliberalism thus: “Neoliberalism is the doctrine of uncontrolled markets: it says that the best route to prosperity is individuals pursuing their own self-interest, and the market is the only way to express that self-interest. It says the state should be small (except for its riot squad and secret police); that financial speculation is good; that inequality is good; that the natural state of humankind is to be a bunch of ruthless individuals, competing with each other.”

I asked him if that is a view actually held by anyone. He said yes and offered a shorter version: “By pursuing your own interest you create the ideal society.” But that idea is as old as Adam Smith, I said. It is not neo- anything. “Inequality is good” is not what anybody actually argues for.

“I think there are two belief systems inside the neoliberal elite. The one they converse with, tempered by social responsibility [and the one they use in private]. Blair and Clinton were neoliberalism: the pursuit of financial profit, combined with the trickle-down of some of the surplus down to the poor.”

Isn’t that just a disparaging description of traditional social democracy, I asked, as encapsulated in the German Social Democrats’ slogan, the market where possible, the state where necessary?

“No, I think traditional social democracy, in Britain anyway, is the representation of the working class with the enlightened middle class where they have a common interest.”

We were not going to agree, so I asked why capitalism needs to be replaced.

“Neoliberalism opened up a technological revolution but it has created a dead end. Financialisation, which has too many syllables but is a new and controversial analytical category in economics, understands the creation of revenue streams to capital direct from people through interest, through credit cards, store credit cards. Our lives are financialised. Once you do that, and then you pump the system full of money at every crisis – elites decided there could not be a crisis, every crisis had to be met by expanding the money supply.

“So Greenspan meets every downturn with money expansion. They understand implicitly the system depends on the removal of social solidarity, so if you were now to have a Thirties-style depression, it would be much rougher than the Thirties. I covered Hurricane Katrina and what was striking was how quickly society broke down.

“If you pump money into a financialised system you raise asset prices to extreme proportions and wages don’t have to rise – that’s what creates the boom-bust pattern but it’s not a steady state, it destroys another part of the state. So my critique of it is beyond moral it is practical. That can’t go on and it doesn’t work.”

An extract from the book was published in The Guardian a few days before we met:

“The extract from the book was received very well by a different set of people than those who normally read my stuff. A lot of people were saying, ‘You’ve said exactly what I was thinking, and you’ve said it slightly more brutally than I was allowing myself to think, and that is the way beyond capitalism is not planning, not state control, not the suppression of the market by force, it is the simple supersession of market forces by things that dissolve it.’

“I think that’s the nerve I’ve hit. I’m not saying there’s an army of anti-capitalists out there. But there’s an army of people that’s unsure about what the dynamics of the society that’s emerging will be.”

Why was It’s All Kicking Off Everywhere popular?

“It tapped into an idea that what was driving the revolutions was not simply Facebook and Twitter but the emergence of a new kind of human being with different attributes, which sociologists call the networked individual. I had a moment of virality there when I wrote this blog, 20 reasons it’s kicking off everywhere, when I was at the BBC.”

What was it like working for the BBC?

“The BBC is brilliant. As long as you don’t mention in any pejorative way the leader of a political party, you can more or less say what you want.”

Could you call yourself a Marxist?

“It’s interesting. The BBC has to censor every book you write: they have to meet the same standards as the broadcasting, which is ridiculous. There was a moment at the BBC when the guy who was censoring the book [It’s All Kicking Off Everywhere] said, ‘I don’t like this passage, it sounds too much like dialectical materialism.’ So I wrote back saying, ‘So if it were Kantian idealism it would be all right?’

“Actually, I’m quite happy to call myself a Marxist at the level of method, because historical materialism as a method is a great tool for understanding history, but as a theory of crisis, as I explain in the book, I think it is inadequate, and there are a lot of tenured academics who are not going to like this book. The long cycle theory supersedes it and is more important for understanding what we are going through than the theory of boom and bust, the theory of business cycles.”

How come you are in the mainstream media?

“It’s bizarre. You only know what the rules are of public service broadcasting when you push at the edges of them. When I joined the BBC they asked, Can you put down your political affiliations and any relevant facts? I said tell me what you mean. And they said, Suppose you’ve been a Conservative MP, you’d have to put that down. When I joined the BBC I put down what I currently was doing which was at the time, which was the Socialist Alliance, which was the pre-Respect [organisation], I’d supported them in the election, so I thought I’d better put that, because that’s what I voted. So I put that and it goes into an HR file. I didn’t go into the BBC or Channel 4 to pursue my own political agenda, but what I can’t help is seeing the world in my own particular way and reporting it, and I would argue that that way is an objective way. It’s just that everyone else seems to see objectivity through the lens of the neoliberal idea set.

“I don’t want to be critical of the BBC because I think we need to defend them against the onslaught and from themselves, but I lived through the MacAlpine debacle; it happened one metre from me at the next desk. I know how badly run the BBC can be. And the Savile [problem] ruined my life for about 18 months, having to work for a programme [Newsnight] that had been smashed up.

“If you employ somebody to do what I do you’ve got to accept that, as long as the metrics are achieved. It is difficult. Look, the video blogs I’ve just done from Greece for Channel 4 probably have more viewers than Channel 4 per night. Broadcasters increasingly want this uniqueness of human individuality. When I’m in Gaza, they want to see my lip quiver when the bomb goes over my head. They want to see me thinking, Shit I’m gonna die. There is a greater value placed on that than on the sang froid British Sandy-Gall-type stiff upper lip these days. But what that then means is that if you want a real human being to appear on screen or in the column of a newspaper then that human being is going to be real, and they are going to come with the ability to make mistakes, to have prejudices, to be biased.

“If your question is how can you be thinker, reporter, novelist, putative playwright, all these things that I do, that’s just me. Capitalism pays me wages for going to work to produce work to a certain standard. But I couldn’t live if all I did was two-minute-thirty packages on Channel 4.”

It is unusual, though, to have a voice on mainstream media that has completely different assumptions, Marxist assumptions –

“They’re not Marxist assumptions, they’re materialist assumptions. Also placing humans at the centre of stories. It just comes out of my experience, not even political experience.

“What I often look for is, What’s the real power structure? You go to a small town in Nigeria and they go, Here’s the main man, and he comes out and shakes your hand and everyone’s looking at this other guy. I have a sense of, Who’s the other guy? What’s he done? And of course he’s usually some crazy imam or something. I like that challenge, to me that is what journalism is, trying to find the real power.”

Mason is an inspiration to many people who support Jeremy Corbyn’s campaign for the Labour leadership. A lot of people look up to you as a theoretician, I say, and he interrupts: “It’s bizarre really because I’m not trying to be a theoretician, I’m trying to be a thinker here, a theoretician is something different.” I’m not sure what the difference is, so I note the paradox that the requirements of public service broadcasting limit what he can say about the Labour leadership election.

“What I can say is the party if it’s not careful is on the point of falling apart. As an analyst of the labour movement, Labour only ever survives as an alliance, an alliance between two lefts, the left of the ruling class and the left of the working class. The four million votes for Ukip are the right of the working class. This is what the starry-eyed middle class don’t understand. There have always been working-class Tories, I’ve lived in a town full of them. Good luck to them.

“The problem is that both sides of that alliance are now pushing for hegemony. So you’ve got Progress pushing really hard for a project that cannot succeed. I’m talking here not judgementally but arithmetically: Blairism cannot take over the Labour Party because it would be a Labour Party funded by Lord Sainsbury. Likewise, the left can’t take over the Labour Party because it’s not big enough in the structures, even if it turns out that maybe 53 per cent do support Corbyn [as suggested by a YouGov poll that day].”

In Postcapitalism, he refers to Red Star, a science-fiction novel written by Alexander Bogdanov in 1909 as a warning to Lenin of the dangers of trying to establish communism prematurely. It features a utopian communist society on Mars with modern factories and no money. Mason begins his account of how the transition to postcapitalism would come about with a character who feels like “a Martian stranded on Earth”, with “a clear view of what society should look like, but no means of getting there”.

“If what I am predicting comes about and large parts of society move to a form of non-money exchange the interesting thing will be what happens. There are two possibilities. One is that we move to a substantially gift economy. That’s the economy that’s effectively modelled in Bogdanov’s Red Star. Bogdanov wrote that for a reason. It is an utterly polemical book that was meant to smash Lenin. He was saying to Lenin if you try to create communism in a backward country where the working class is so ill educated and unliberated [it will fail]. In Bogdanov’s book, people swap genders. It’s really interesting. Why did a Marxist in 1909, whose entire desire was for workers to liberate themselves from their mental chains, why did he make the heroes of his book effectively transgender? Because he was trying to shove down the throats of these utterly sclerotic Leninist cadres that the human revolution comes first. That I think is relevant.

“The software developer in the shower knows that if she has an idea she is supposed to write it down and it belongs to her employer. Does that happen? No. The information is in revolt against the market. It will be a long revolt. There will always be a return for a new idea.”

Which you’ve got to hope because you want to get some money for this book.

“Of course the economics of book production are completely broken, but leave that aside, I’ve begun to try to liberate some of the stuff that I produce from pure commerciality. I mean, most of my work has been done as an employee, so the intellectual property resides with other people.

“I published an essay through creative commons. If you throw the gift into the world, then good things come back to you. Some people published it, for free, which is great, and it’s led to all kinds of interesting conversations that may or may not turn into commercial propositions with novelists, theatre people. That’s what free stuff does.

“The reason I can do it is because I earn enough already and I have free time already. But this is not like the anomaly of an elite, there are millions of people out there whose work and leisure time is so blurred that the ownership of what they do and where, whilst being really clear when it comes to aircraft design, is not so clear when it comes to pure ideas.

“Many of us who work in this space of ideas realise we are in the golden age of intellectual creativity. But we can’t monetise it all. Look, the greatest plays being put on in London are being put on subsidised by the state or somebody else; the shittiest plays are being put on by – I won’t name him – a massive impresario who only puts on shit plays in giant theatres. So what good’s the market to us?”

His vision of postcapitalism seems to rely quite heavily on the non-market, collaborative example of Wikipedia, I say.

“There’s Wikipedia, but there are a whole lot of internet tools that are non-spectacular, most software, most of the stuff that people use to write other stuff is actually free. This sector of the economy is non-negligible. It is entirely possible that we will see a city set up with a free Uber. All that Uber is is a rent-seeking exchange. But rent-seeking operations are really easy to undermine by regulation. You could say, Look guys, Lambeth council has set up an Uber, and has decreed that only its Uber would be used in Lambeth. You could do that.”

He talks about his recent experience filming with anti-austerity protesters in Greece as an example of the postcapitalist system in embryo.

“As you move through it from one beleaguered souvlaki place to the next what you are mapping is the informal economy where the default way of running things is through barter, sharing, non-market, some market, the market injects the liquidity. So I’m there, Paul, I arrive with a wad of cash, demanding a receipt and saying I need the property rights to the following footage, but when you watch where the cash goes it’s sucked up into an economic system that is very, very non-market. It’s just bizarre.

“The movements understand this better than I have expressed it in the book because I want the book to be read by people who don’t know about this sort of thing. But what the movements haven’t understood is the power of the state.

“The state saw what was happening and tried to regulate factories in the 1880s and said let’s clear a space for this kind of economics. If we did the modicum of the same with the postcapitalist sector it would quite rapidly grow. Even if it is only a social-democratic palliative, some social democrats will see this benighted factory in east Germany [and they might say] they could do with a few co-ops. I’m quite happy for this to be a kit of parts, that the revolutionaries take from it the revolutionary bits and the reformists take the reform bit.”

As we discuss revolutionary reformism – “in its time, Blairism might have been a revolutionary reform movement; Podemos [in Spain] is the most clearly revolutionary reformist movement now” – I am intrigued by his attitude to violence. To most people, I say, revolution implies violence.

“Not to me, not to me. I don’t mean violent revolution at all.”

You must have been attracted to it in your youth?

“I was never in the Militant tendency, but you do remember it used to go out of its way, I think quite rightly, to explain to people, it’s the state that’s going to be violent against people not the other way round.” (I do remember that: he is quite right. I thought it monstrous then and am surprised to come across someone still making that argument 30 years later.)

“Now there are levels of state violence in democracies that are way in excess of anything that happened under Thatcherism,” he says. “The default response is robocop, surveillance –”

Surveillance isn’t violence, I object.

“It’s a form of violence.”

What?

“These cops who slept with unsuspecting women on the left: you could argue that’s rape. There are implied levels of violence in the state’s response to even quite mild anti-establishment protest. People know that if they go on a demo against fracking they will be tear-gassed, dragged away and beaten –”

In Britain?

“They certainly will be dragged away and beaten. Yes, of course they will be. The Metropolitan have now got a form of zero tolerance of unorganised protest to a level that absolutely it did not have in say the miners’ strike. But this book’s about the world not just Britain.”

The miners’ strike is a reference point in Mason’s life.

“I was – the correct term is – a supporter, of a group called Workers’ Power because we were inside the Labour Party and therefore you weren’t allowed to have alternative membership. As a student and a young guy in my 20s. All the way through the Eighties, the miners’ strike, the print strike, but I came to the conclusion in the late 1990s that the anti-globalisation movement had a point. And I also came to the conclusion and I elaborate this at great length [in Postcapitalism] and were it not for Penguin it would be at even greater length, that 20th-century Marxism was built on a misunderstanding of what the working class wants. I try and prove it: there is a big section in the middle about the history of skill, of work. If capitalism has a beginning a middle and an end, then the labour movement probably also has a beginning a middle and an end.”

It has ended, hasn’t it?

“I don’t think so. In Greece it’s not dead. It’s becoming, the Marxist term would be, sublated into something wider. It is this bigger movement of connected people.

“The labour movement is a really important part of my life, my culture, even as a working journalist it is important to me that I am in a union. The culture I’m from is very ingrained, mining Labour.”

He admires the ability of “talented people” in the RMT (National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers) to “run rings round London Transport”. And he was able to draw on his experience to bring comfort to Greek leftists disappointed by the Syriza government’s acceptance of the harsh terms demanded by the rest of the eurozone.

“I lived through the Greek defeat; it’s like being in the Blitz. At the end of it all when they felt so bad about Syriza retreating I said to them, It’s nothing at all like the miners’ strike. In the miners’ strike we had the moral defeat of an entire – [what was he going to say? Entire class?] the people who beat Hitler, as Lord Macmillan called them. That’s a defeat. I think people have found it quite interesting to have me say that. Because to them it’s the worst thing that’s ever happened. To me, the worst thing that’s ever happened to my town, my society, my family was the defeat of the miners. That was a shattering experience.”

Postcapitalism may be a way of avenging that defeat, predicting the end of the forces that caused it. But Mason seems to me like the Martian in Bogdanov’s Red Star, stranded on Earth with a clear view of a different and better way of organising society, but with little idea of how to get there.

Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future, by Paul Mason, published by Allen Lane, £16.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments