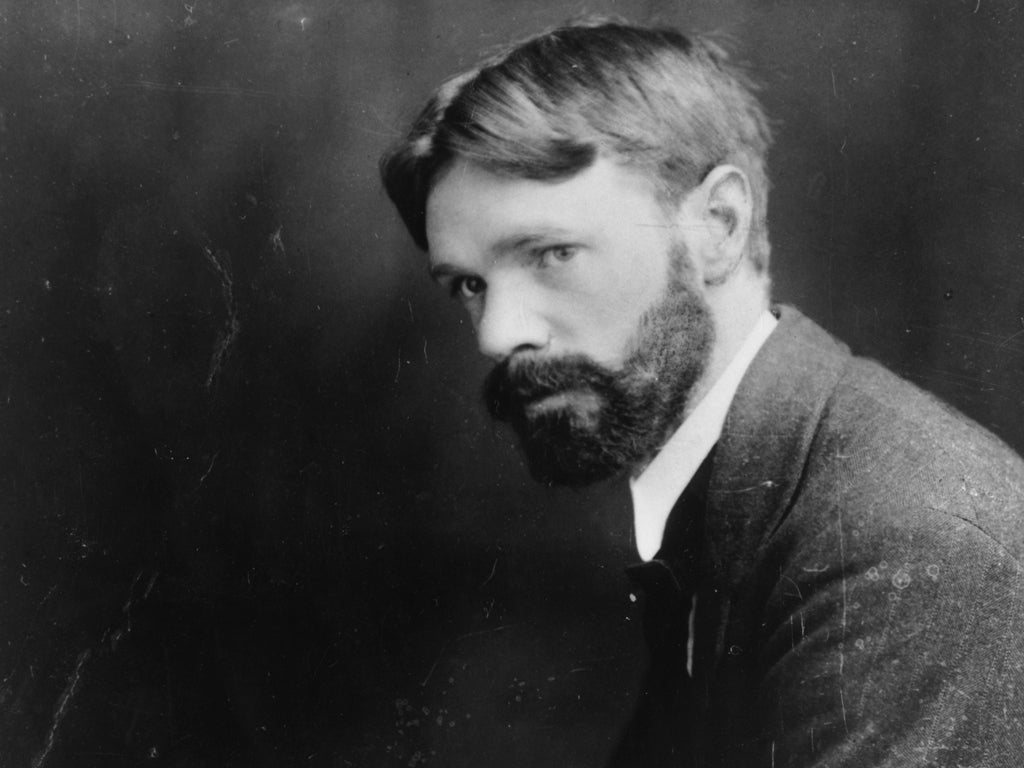

A fiver says it should be D H Lawrence’s face on the back of one of our notes

If Jane Austen had genius, then we need another word again for what Lawrence had

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One of the more enigmatic statements on the British economy made by Mervyn King before he bowed out was that Jane Austen was waiting in the wings.

Anyone not paying full attention – as I wasn’t – might have supposed that King had finally lost his marbles: were things really that moribund in the City that his best replacement as Governor of the Bank of England was a long-dead novelist, no matter how alive her prose? It turned out that what Jane Austen was waiting in the wings for was the chance to have her face on the £10 note.

Alien as such a conjunction of literature and filthy lucre is to an old idealist like me, I applaud the choice. But if that’s the tenner sorted, may I put forward D H Lawrence as the new face of our fiver? This year is not only the 200th anniversary of the publication of Pride and Prejudice; it is also the 100th birthday of Sons and Lovers. Lawrence didn’t like Jane Austen much, and she probably wouldn’t have cared for him, but there’s no law that says the people on our currency have to get on. As for the conjunction of filthy lucre and literature being even more inappropriate in the case of Lawrence, who scarcely earned a penny from his work and scorned materialism – “Money poisons you when you’ve got it, and starves you when you haven’t,” he wrote in Lady Chatterley’s Lover – well, there have been stranger marriages. I once owned a D H Lawrence Medal for Promptness that came as a reward for signing up without delay to a book society and agreeing to take six volumes a year, and who has ever thought of Lawrence as notable for promptness?

We don’t, it seems to me – promptness apart – value Lawrence as highly as we should. He wrote two, maybe three, of the greatest 20th-century English novels, countless very fine short stories, some of the sharpest literary criticism (find me something to beat Studies in Classic American Literature), much original poetry, wonderful travel books, essays, journalism, letters, and forget about the paintings. All this before his 45th year. If Jane Austen had genius – and I yield to no one in my admiration for it – then we need another word again for what Lawrence had. It’s no surprise he had recourse so often to language whose mysticism makes our prosaic times uneasy: when the well of your creativity is so deep, you must wonder who is speaking inside you and what impulses you are answering. Of such bemusement are prophets made.

Lacking deep wells of creativity ourselves, we scorn the wild words and warnings of such visionary writers, mistrust their fluency and vehemence, fear their long grey beards and glittering eyes, preferring the reserved, spare, well-shaved demeanour of those who work the surfaces of things.

Lawrence is not, for these and other reasons, the ideal writer for a reading group to tackle. This is not the first time I have addressed the phenomenon of the reading group. If anything should give one hope for the continuing vitality of our culture, it’s the reading group. People giving up their time, willingly, to exchange informed, animated judgements about works of literature over wine and canapés – reader, I can think of nothing better. It’s what passes as informed, animated judgement that’s the problem.

Chairing the Guardian Reading Group’s assault on Sons and Lovers recently, Sam Jordison, author of Sod That!: 103 Things Not to Do Before You Die, ventures to suggest that reading D H Lawrence might be one of them. “We’ve already developed quite a rap sheet against Lawrence here on the Reading Group,” he writes, “and to that growing list ... I can also add being silly, tedious and sloppy.” Not great critical terms those, I would venture to suggest in return, not least as you must wonder why, if the faults of this novel are so glaringly obvious, readers as astute as Philip Larkin, who found “nearly every page of it absolutely perfect”, and Blake Morrison, who only the other day described it as “momentous – a great book”, failed to spot them.

I don’t say we must bow before authority; in the great democracy of reading, our first duty is to report what we find. But we must also face the fact that sometimes all we find is ourselves. That which we call tedious might be no more than the echo of our limited capacity to be interested; that which we call silly no more than a prim refusal to let a writer take us where we are unwilling emotionally or unable intellectually to go.

Jordison cites the following passage from Sons and Lovers as evidence of Lawrence’s silliness and sloppiness. “She felt the accuracy with which he caught her, exactly at the right moment, and the exactly proportionate strength of his thrust, and she was afraid. Down to her bowels went the hot wave of fear. She was in his hands. Again, firm and inevitable came the thrust at the right moment. She gripped the rope, almost swooning.”

“That’s a description,” says Jordison, “of Paul pushing Miriam on a rope swing. Steady on!” Steady on, Turner, it’s only a bloody sunset! Steady on, Wagner, it’s only a ring! But it’s not necessary to pursue the Michael Winner Calm Down Dear school of criticism to its philistine conclusion, because Jordison is doubly wrong in this instance – the passage is not a description of Paul pushing Miriam, it’s a description of Miriam being pushed. The drama of quivering sexual fearfulness is entirely hers. To accuse Lawrence of overwroughtness when overwroughtness is his subject is like accusing Shakespeare of jealousy for creating Othello.

Reading is a two-way activity: some books fail us, but it happens just as frequently that we fail them. There’s silly, sloppy writing out there, but there’s silly, sloppy reading too.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments