Will Self: Joy Division and a Vesta curry

When I was 20 I tried to spend Christmas alone. It was a protest – of sorts – and also an actualisation of a deep and twisted disappointment in family, love, cosiness and cheer – all of which I held to be, in this the climactic period of my protracted adolescence, Yuletide lies and festering festive spirits.

My parents' marriage, which for many years had resembled a gnawed upon string of gristle, had finally and greasily disintegrated. My mother was spending the winter on the Costa Blanca, in a whitewashed house full of mice that animated her own scuttling phobias. My father had recently emigrated to Australia with his new love – a nice enough person, if I could've appreciated it at the time, but all I seized upon was her proclivity for writing spiritual doggerel. I can't remember where my brothers were.

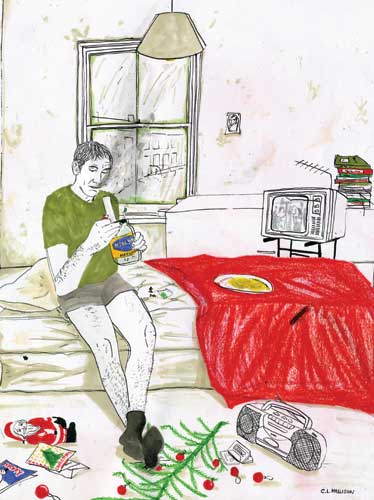

It was my final year at university, and together with five women (something of a coup), I shared a damp and cavernous redbrick house in the Jericho neighbourhood of Oxford. My bed was a makeshift pallet of lumpy mattresses; I had turned the wardrobe on its side. All my dog-eared paperbacks were piled up in a nook, and the only decoration on the walls were the Rorschach blots of moist plaster and a tiny picture of Kleist, the German Romantic writer who killed himself in a suicide pact at the age of 34.

In this unprepossessing environment I smoked a water pipe made from a large mayonnaise jar and a length of shower fitment; when I drew on this, the .002-scale plastic soldiers I'd put inside the bong – US Marines as I recall – would roil and moil in a vortex of hash smoke and fluid, looking like the doomed in John Martin's apocalyptic painting The Fall of Babylon. When I wasn't haranguing anyone who'd listen on the subjects of nihilism and my own rampant anomie, I'd listen to Joy Division on my tape recorder (remember those!), or watch films on my four-inch black-and-white television – epics for preference. There was something immensely satisfying about the juxtaposition between Land of the Pharaohs, and that upended shoebox of a room in Jericho.

You get the picture: I was a regulation scrofulous and disaffected student, in those happily miserable times before higher education became fixated by the ridiculous – and mercenary – idea that it was part of a career path, and that pliant youths should be forcibly moulded into productive units for use in the burgeoning economy.

It was cold that winter, and scuzzy rime built up inside the tall, ill-fitting sash windows. Even with the noxious gas fire continually twittering on in the corner my room felt exposed to the winds blowing from the Urals. Early the following year Russian tanks would roll into Poland. Frankly, I wouldn't have minded if they'd invaded my room – for there was no solidarity to speak of. I eschewed the overtures of my housemates and packed them off to their families: Sarah with her dyed vermilion hair and spiky earrings; Polly with her silk dressing-gown and her lapsang souchong; Imogen with her leather jacket and her growling BSA motorbike.

When they were all gone, I went to the local shop and bought the most antithetical Christmas dinner I could think of; no buxom brown fowl for me, oh no, this not-so Tiny Tim would slurp down a Vesta chicken curry, his only company the rattling ghosts of Christmas past. Because the truth was that Christmas had never been that great in my family of origin. To paraphrase Tolstoy, all unhappy families may be different, but there's something about festivals, celebrations and anniversaries that makes them behave in the same way: badly. The last Christmas we had spent in my natal home, two years before, had been distinguished by my brother and I having a stand-up fist fight in the street, smiting one another until we fell into the privet – a small suburban nightmare.

No, I would spend Christmas, and the nights that book-ended it, alone, in bed. There would be no decorations, nor carolling, no wassailing, no sub-mistletoe canoodling, no stuffing, no adoring of the Christ Child, no saturnalia, no potlatch. All I'd do was agitate the Marines and squint at the telly (but only when it was showing epics). Like all kingly babies, I imagined myself to have a Divine Right; it was as if, by ruining Christmas for myself I could somehow ruin it for everyone else. If I weren't going to have gifts, treats and sweetmeats, I would dash them from the hands of all.

It all went swimmingly. Christmas Day dawned satisfyingly bleak and gloomy: there was no snow to make the dull suburban street look anything but bare and uninviting. I squatted in my tumbledown bed re-enacting Iwo Jima .002-scale. At approximately lunchtime I went into the kitchen and boiled my bags of rice and chicken slop in their plastic bags, but when I got them on to the plate they tasted so unpalatable I binned them, and shuffled back to bed.

But then, horror of horrors, at about four in the afternoon there came a loud and insistent knocking. I considered not answering it and stayed doggo, but then jolly voices were raised – calling out my name, and residual manners forced me upright. When I swung open the front door there was my girlfriend, together with her parents and her younger brother. I had requested, then pleaded, and finally insisted that she leave me alone – I wanted no part of her cheerful, cosy, loving family. She, however, had ignored my entreaties, reasoning – quite rightly – that here was a Scrooge who needed saving from himself: her family were on their way from London to visit relatives in Cheltenham, why on earth shouldn't they drop by.

I think I made them tea – but I may not have. I certainly recall that there was a cosmic awkwardness in the collision between my attitudinising and their hearty affect, just as my undress dishevelment looked worse than ever set beside their smart holiday attire. They didn't stop for long – I stuck to my guns and refused to go with them. And when they were gone I discovered that they'd done me a favour, for things were far worse than before; instead of being the heroic captain of my solitude, I was merely lonely. I like to think I understood that very day – although, it may have been a lesson it took me longer to absorb – that deliberately being alone on Christmas Day was a bad move; that it was tempting fate to toy with isolation, when life, with all its impulsive alacrity, may at any time capriciously thrust you out in the cold.

Will Self's latest novel, 'The Butt', is published by Bloomsbury

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks