Tom Sutcliffe: Ancient discovery raises the spirits

The week in culture

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Discrepancy of belief is, I imagine, a fairly familiar experience for a lot of us when it comes to big exhibitions of classical or ancient art. What I mean is this. You go to a big show of religious art – or just to one of the big established national collections with a lot of religious paintings – and you take it for granted that there will have been a tectonic shift between the sensibility that first created or viewed these works of art and the sensibility you are bringing into play. This shift is almost never a simple matter. There will, presumably, have been people who looked at Masaccio's Expulsion from the Garden of Eden at the time it was painted and taken it as a straightforward attempt to depict a real historical event. At the same moment, one imagines, a whole range of other responses would have existed, from outright scepticism (with regards to its literal content at least) to some version of a modern sophistication of belief, in which this event is seen as somehow metaphorical of man's fallen estate. And we can't make any complacent assumptions about the beliefs that feed into a painting either. What was Michelangelo thinking as he painted The Last Judgement on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel? That this was a magnificently rich subject matter that would allow him to paint pretty much anything he wanted? Or that he was conjuring into visible form an event that would, one day, take place and that it might look something like this?

The discrepancy is so familiar to us that it isn't really a problem. That may be because we've negotiated so many ways to get round it. Believers have less of a problem to begin with, of course, since the subject matter is aligned (I'm talking, for the sake of argument, of Christian viewers and Christian art) with their own convictions. But even non-believers have endless means of escaping the literal religious statement of a work of art, into beauty of technique, or curiosities of scholarship or contingent secular truths. You don't have to believe that Mary cradled Jesus and that Jesus was the son of God, to be moved by the Michelangelo Pietà, since the religious roots of the work have been almost entirely overshadowed by its human truth, its attentiveness to the experience of grief. And that's true even of highly specific bits of religious art. Byzantine icons can still cause a bit of a problem for the sturdily secular viewer, but even there we have ways of surmounting the hurdle that what was centrally true for the creator of the work (or the client who commissioned it) may strike us as little better than a fairy tale.

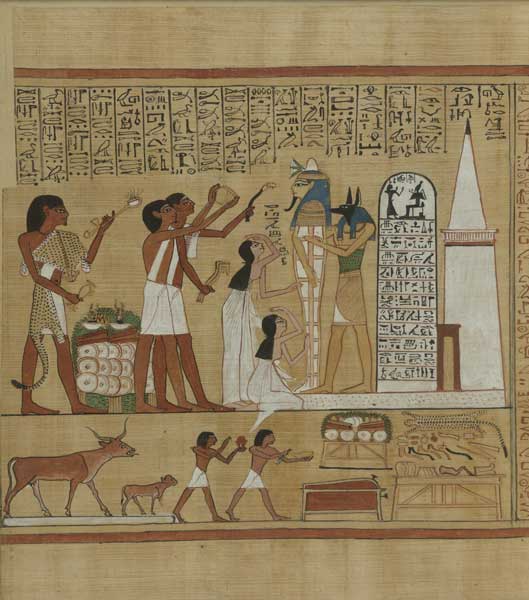

So it's unusual to go to a show and be besieged by thoughts about credulity, as happened to me walking round the British Museum's big new exhibition on the Egyptian Book of the Dead. It's an absolutely fascinating gathering of objects, incidentally, and well worth a visit. But it seems to me an exhibition in which the traditional escape routes from the beliefs that have given rise to the work simply aren't available. There's some brave talk from the curators about the "exquisite" nature of the paintings on the papyri and the beauty of the illustrations. But the truth is – as the exhibition itself makes plain – that quite a few of these documents are upmarket bits of pro forma stationery, adapted to specific clients from an off-the-peg production (the Book of the Dead was a cross between a visa for the afterlife, a posthumous travel-guide and a spiritual insurance policy). And it's simply impossible to avoid the question – as you look, say, at a depiction of the deceased's heart being weighed in the balance while a chimerical creature called the Devourer waits to pounce on the unworthy – of what the people who made these things really, truly believed. Did the Ancient Egyptians have their equivalent of trendy vicars, saying "Well, of course, the Devourer isn't to be taken literally." Or were the people who purchased these things just going through the motions, in much the way that a modern bridegroom might promise lifetime fidelity before God while knowing perfectly well that it might not work out? Impossible to know, of course. But also oddly exciting to encounter a cosmology so matter-of-factly alien, and so resistant to the standard forms of neutralisation.

The crescendo that has lasted for two decades

I caught the latest THX trailer in a cinema the other day – a short film called Amazing Life, in which alien-looking plant-instrument hybrids showcase the range and quality of the cinema sound-system. As usual it ended with the THX audio sting – a reverberant crescendo which is known as "Deep Note". The trademark description of this sonorous logo explains that it "consists of 30 voices over seven measures, starting in a narrow range, 200 to 400Hz and slowly diverting to preselected pitches encompassing three octaves". For the less technically minded, it might be better described as a very big orchestra having a collective orgasm. I can vaguely remember the first time I heard it, back in the Eighties, and how thrilling it seemed then, both because of the volume and the way that a set of sharply particular sounds converged into one massive chord. And oddly enough – over 20 years on – it's still delivering. The trailers aren't always brilliant, though the best of them offer a kind of pure, narrativeless spectacle that takes you back to the early days of cinema. And, unless you have a neighbour-distressing sound system, the cinema is still the only place where you can get the full effect. You can watch the trailers online, but it just isn't the same.

Who is the original Kip Stringer?

The news that Sotheby's in New York had sold an Andy Warhol Coke bottle painting for £22.11m set off a rather larger blip on my cultural radar than it would usually have done. Sadly, this isn't because I have an Andy Warhol that I'm planning to put up for sale, but because I'd just finished reading Steve Martin's An Object of Beauty, a Gatsbyesque tale of the rise and fall of a New York art dealer, which clearly draws on Martin's own familiarity with the contemporary art market. A successful Warhol sale features in the book, sending a galvanising little jolt through the trade. And since the novel mixes real New York art figures with fictional creations, that real world event echoed back into a fictional world that was still in my head. What I want to know now, though, is who supplied the inspiration for Kip Stringer, an egregious English curator who appears in the most splenetic passages of the novel? Martin's description "he took the artist's right to be obscure and turned it into a curator's right" doesn't exactly help us narrow the field, though Kip's success with a show in which "Pollock and Monet were hung in the same room under the premise that the heading 'Material/Memory' or 'Object/ Distance/Fragility' clarified everything" seems to be pointing vaguely Tate-ward.

t.sutcliffe@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments