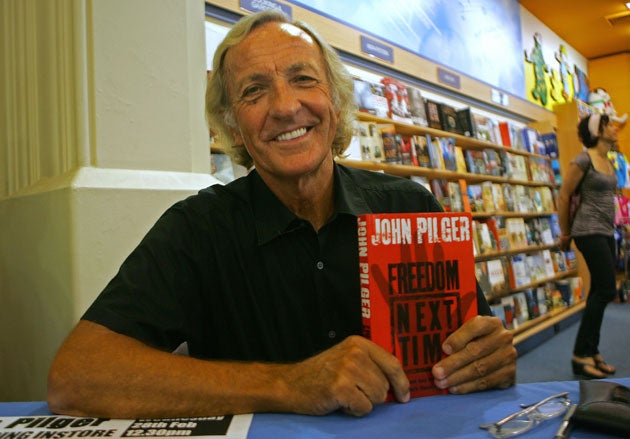

John Pilger: 'I have watched the political ground shift beneath my feet'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.He has pursued almost a crusade, a missionary like zeal against the Western world, its inadequacies and corruptions, for almost 40 years. Few politicians of recent times have escaped the withering criticisms, the icy blast of his rhetoric. He once disparagingly called South African former Finance Minister Trevor Manuel "a long haired biker of the 1980s".

Maybe, just maybe the driving force for journalist John Pilger's life work in exposing the rogue activities of politicians and countries, rooting out the tragedies from which he alleges their policies too often flow, come from his mother, back in Australia more than 50 years ago.

Pilger still recalls asking her about some wealthy people whom they saw one day in the expensive Belle View suburb of Sydney where, as he puts it now, the "robber barons" of Australia lived. "I grew up in pretty humble circumstances near the best beach in the world, Bondi, in Sydney. What my mother said one day was, 'These people are not better than us, just better off.'"

Were those words the inspiration for his life's work?

"I don’t know," he says.

His was, he confirms, a very class conscious family. He acknowledges the influence of his mother and his father particularly in making him aware of the differences of class and money and why they existed. "We didn't read Marx but we did read a lot of books. Both parents believed in that very strongly and it certainly had a real effect on me."

John Pilger, arguably the world’s most renowned campaigning journalist, will be 70 this October. He has written more than a dozen books, produced around 16 documentaries, a film, play and DVDs. He has worked for most of the great newspapers and news magazines around the world. His reputation burgeoned in his famous campaigning days of the 1960s and 1970s, when he wrote revealingly from wars like Vietnam for the Daily Mirror.

Those were the great days of journalism when the Pilgers of the world, enjoyed the financial support of wealthy individual media barons who would indulge them in spreading their wings across the global map to write searingly of the injustices they saw in all corners of the world. Vietnam, Cambodia, South Africa... Pilger's words shone a light upon the cruelties and injustices in murky, far flung corners.

His reputation has become synonymous with his deeply damaging assessment of countries in the western world, their policies and politicians. A left wing firebrand? He smiles, suggesting that if we call the wish to expose injustice, to point out policies of genocide as left wing, so be it. To him, it is important to lay such facts before the world’s populations so they can make their own judgements.

But doesn’t every country have skeletons in its cupboard?

"Yes. But the skeletons that rattle with such a din almost to deafness are those in former Empires. I have never understood how people can view the world without viewing it through the framework of possession of power from outside Empires.

"They have always fascinated me. Countries that have been part of Empires have skeletons that can miraculously come alive and present themselves to us. Look at the way the British Empire that I grew up with in Australia operated and what it was about. Three things seemed to sum it up: cricket, royalty and boredom. Nothing, it seemed, happened among this benign force that covered the world. All was wonderful and calm.

"But that was nonsense. You only have to go to India or read Mike Davies’ books on early 19th Century India to understand the truth."

But doesn’t the world have its fill of bad news. Aren’t Pilger's words, that seem to damn so great a section of humanity, not wearying in time? And at nearly 70, has not the flame of anger and protest at so much that’s wrong in the world started to moderate with the approach of old age ?

Frankly, no; it has the opposite effect, he tells me. And he offers the quintessential response to such a philosophy. "I don’t understand entirely those who decide to do a U-turn in their lives and become something else. It's almost as if they say goodbye to a part of their life that had no meaning.

"As the world has become more dangerous I have become more aware of that and have watched the political ground shift beneath my feet. 30 or 40 years ago you could be described as a wet liberal but these days you're considered a wild eyed radical. But it's a natural progression.

"The longer you live and observe what small groups of your fellow humans would like to do to the larger groups, the angrier you become."

But when he sees so many fellow travellers from the 1960s now fat cats in business or Parliamentarians with warped morals, doesn't it depress him?

"Frankly, yes. I don't know many Parliamentarians but I do know people who once wanted to convince the world that they wanted to change it and brought people along with them. But then they changed direction for reasons of career and opportunities. That is depressing."

Human nature? Pilger won't swallow that one. Too easy to blame it on that, he asserts; it is political nature. Most people, he says, follow a reasonably consistent line in their lives of decency and adhering to certain principles. Those who aspire to power are seduced by it.

But given Pilger's renowned and fiercely prosecuted left wing views, was it not the greatest oxymoron that he accepted last year a Doctorate from a South African University named Rhodes? Have we not moved into the world of poacher turned gamekeeper? There is a lot of laughter (but note, a brevity of words) at my disingenuous suggestion.

"No."

"Why not?"

"I don’t think the Vice Chancellor and his staff are in any way devotees of Rhodes. Besides, his name is on a lot of things around the world. It's very important we understand exactly who Rhodes was. The spirit in which it (his award) was offered was an understanding of the critical work I have done on South Africa."

We talk about last November's US Elections and the arrival of Barack Obama, but he sees scant difference between any of the candidates.

"Had Bill Clinton not been around all those years ago and had John McCain not been in prison (as a shot down pilot in Vietnam), it would have been a perfect marriage between McCain and Hilary Clinton. They are two of a kind."

And Obama?

"He has this ridiculous, cultish following that has a touch of Princess Diana about it. But the truth about Obama is that his main backers are big business people like Goldman Sachs and City Corporation."

But, now in office, are not the Democrats offering a lighter touch on the tiller than the brusque, brutal Bush and his Republicans ?

"Remember," he scolds me, "a Democrat dropped the atom bomb and another invaded Vietnam. Yes, there are differences in domestic policies but it can’t be any worse than it is.

"These people are simply given a turn at the wheel. The USA is like Britain and Spain were with their great Empires. A permanent war culture exists and always has done. It's a rapacious system; just look at the history of Latin America since the 19th Century. But it doesn’t mean it's invincible. However, some of the most exciting political people I have ever met have been in the US."

But, he concedes, he has covered four US Presidential elections and they pull out the same speech each time. FD Roosevelt, JFK, Clinton, Obama, McCain. Obama, he thinks, has taken what he calls the vacuity to new heights. "He has made his platform based on change, whatever that is," says Pilger.

"Of course, the truth is, the same forces run America. The fact is, the key man behind Obama is Zbigniew Brzezinski and he started the whole thing in Afghanistan."

And finally, what of South Africa and Pilger’s thoughts on this tremendous, tortuous, tainted, terrific, tantalising enigma of a land? What does he make of Jacob Zuma - is he a populist, potentially a more dynamic leader than Mbeki or just a self seeking opportunist? Is he dangerous and where will South Africa be in 10 or 20 years time? Does he see tribal warfare as a likely outcome long term?

Where to start? Well, does he see the current scenario of poverty, violence and crime ever changing in parts of South Africa like Alexandra and Khayelitsha townships?

"It will change if there is a political will, to change. Nothing ever changes by osmosis; it has to change with a political programme and although there has been a vast amount of political goodwill in South Africa, there has not been the political programme to change or to lift the majority of people out of poverty. In my experiences in all sorts of places, poverty is the root cause of many if not most of the iniquities that are blighting South Africa at the moment.

"There are clearly more specific reasons but it’s not rocket science. Had there been a programme that took the spirit of the freedom charter and applied all the promises that were given by the ANC leadership before 1994, I would have thought that by now much of the poverty would have been eroded."

So who was to blame? Mandela? Mbeki? Or both?

"Mandela is a fascinating character whose leadership was unique and invaluable. I am not sure he was a political leader but when I met him it was clear to me that he was an inspirational leader. He had a grace and power about his personality you could see that played a vital role in changing things.

"But above all with Mandela, perhaps he was an ANC loyalist and when the ANC went in a certain direction, I am not sure it was entirely the one he wanted it to go in. But he felt it was his duty to go along with that. Yet some of his campaigns in international affairs were terrific, particularly on Palestine where his outspoken views had a huge effect. Mandela is a contradictory character but he did deliver for his country and his sacrifice delivered inspirational leadership. But he needed complimentary political leadership."

And Mbeki? Pilger doesn’t believe he was the right man for the task of following Madiba. "He was determined, it seemed to me, to follow an orthodox route in economic terms; he decided South Africa would join the great global economy. He had all these voices whispering at him from around the world saying South Africa must do that.

"The tragedy of this was that South Africa occupied a very special place in the world’s consciousness at that time and it was one of those historical opportunities where South Africa could have gone its own way and the rulers of the world couldn’t have done a great deal about it. But instead it went the orthodox way."

So nothing much was achieved in reality? "No, there have been huge changes there and to deny those is just dishonest," he avows. "But when you go into a township and find people having their water cut off or people saying that under apartheid it was actually better in economic terms, that is not very good.

"For most people, what really must be most difficult to accept is the sight of a new black class and the idea that there is money but it is being siphoned off by a small group of people with class connections."

And Zuma? Pilger calls him an African Peron. He says he leads an organisation whose political, economic and social policies are not working for the majority of South Africans. So will he prove to be totally different?

"Although his personality is larger than life and more vivid than Mbeki's, is he all that different? I don't know. When he has gone abroad he has done what most ANC leaders have done: go to the rulers of the world and reassure them and the bankers. But it's not the bankers who need to be reassured, it's the majority of the people in South Africa who need reassurance.

"So if you ask me whether he is going to change ANC policy, my answer is, it doesn’t seem likely to me. Zuma has played up the tribalism but there is a huge amount of goodwill in South Africa to resolve the problems of the country politically. So I think a political solution would overcome tribalism."

But isn’t the uncertainty a dangerous vacuum? "Well, the ANC seems like a monolith but its policies are being opposed right across the spectrum. And it is the spirit of that popular resistance to these orthodox economic policies that can effect changes in South Africa. If there are no political or economic changes then people will become frustrated and a mass movement will demand change. It depends whether the political class opens up to allow these changes. If it doesn’t, they will have failed and Mandela himself warned about that.

"But we should not get too gloomy about it all. South Africa could be an amazing country, there's no doubt about that."

For sure, Pilger will watch it all unfold with his usual stern gaze.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments