Graeme Pollock: 'Cricket has become far too financial'

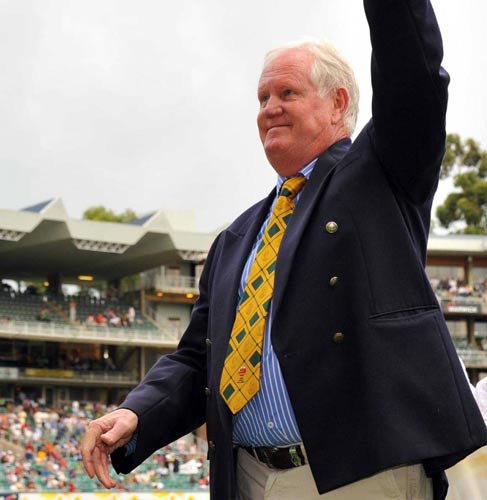

The hand that once guided a piece of willow onto leather, sending it streaking to the boundaries of the cricketing world, was used expressively to make a point.

If, said Graeme Pollock, that long ago era of the 1960s to 1970 was one of South African cricket's finest, graced as it was by some of the greatest talents the sport in this country has ever produced, then why have such outstanding cricketing minds been lost to the country?

"Barry Richards, Clive Rice, Mike Procter and so many others – guys like these should be contributing to South African cricket. It is a sad state of affairs their talents are not required to assist South African cricket. They have been abandoned and the loss of such talented people disappoints me."

Turn the sporting pages of this great nation and it won't be long until you come to Robert Graeme Pollock. As a young player, he burst onto the scene with the splendour and beauty of spring flowers in Namaqualand, the colour and spectacle simply dazzling. At 19, he was selected for the 1963/64 South African tour of Australia and in the 3rd Test at Sydney made an exquisite 122.

The legendary Sir Donald Bradman, who saw the innings, told the South African youngster later "The next time you decide to play like that, send me a telegram." One hopes Pollock kept his side of the deal because Bradman didn't have to wait long. In the next Test of that tour in Adelaide, Bradman's home city, Pollock shared a record South African 3rd wicket stand of 341 with Eddie Barlow, finishing with 175.

To see Pollock, one of the world's most graceful batsmen and arguably the finest left hander of all time, caressing a ball through the covers was to witness sporting poetry. He dismissed with aplomb the snarling aggression, the physical intent of bowlers, daring his nemesis to do their worst. The product of their efforts was invariably despatched to distant corners of a ground.

This was a Keats in white flannels, a man who brought rhythm, flow and a beauteous movement to his craft.

Pollock played cricket for 27 years, from 1960-1987 but the apartheid era ensured his brilliant international career would be truncated to an absurdly brief 23 Tests. Yet in that time, he scored 2256 runs at an average of 60.97. He made seven 100s and eleven 50s. Truly, here was a run machine of such elegance it was a tragedy it was not allowed to flourish.

Of course, he always knew his career, his repute would be associated with the stain of apartheid. That wasn't his fault; he was simply a victim of timing, of circumstances. Nor could he be condemned as a silent voice, for as he says "In 1971, when I captained a team comprising the Rest of South Africa XI, I issued a statement saying that merit was the only criteria. Yet the question always comes up, what did you do in the apartheid years, did you make an effort?

"Nevertheless, recent years have been pretty hard going. Those people who played in the old era haven't been accepted to the same degree. It is felt that South African cricket only started from 1992."

In those dark years, when the cricketing world closed its doors to South Africa, players like Graeme Pollock were humiliated. They were ostracised, ignored. When the MCC celebrated its Bi-Centenary Test at Lords, Pollock was not even invited because of his nationality. He went because he wanted to be there but, as he put it, had to slide in the back door, without an invitation to any of the functions.

Yet he insists today, sitting at his home in Johannesburg "There is no doubt isolation was absolutely warranted. I accepted then and still do that it was the way to change things. Without their favourite sport, people started thinking ‘We can't survive'. Cricket was the first to be isolated because it could never be controlled from a security point of view. Rugby was easier to control and so they played on.

"But total isolation of all our sports would have ended it sooner. We ended up fighting the whole world and it had to happen. No sane-minded person could have thought otherwise. It was a tragedy from a cricketing point of view that era had to stop but not from the point of view of the country. Things weren't right, we had to change."

If it were to happen today, of course, the top players from such a country would simply switch their allegiance; witness the likes of Allan Lamb, Robin Smith, Kepler Wessells and Kevin Pietersen. Why didn't Pollock leave too and make a new life elsewhere ?

"Nobody knew how long this isolation would go on. I had an offer to go to Australia and play for Packer but turned it down because I still thought there was hope. But it was difficult; I was married, had a couple of young kids and couldn't go charging around the world playing fully professional cricket. It was only from about 1992 that people became full professionals. In my era, almost everyone worked."

By 1987, Pollock's career was over. But if he anticipated becoming instrumental in guiding and preparing the new generation of South African cricketers, he was to be sadly mistaken. "I was ready to make a contribution but I wasn't allowed to because I had been part of the old regime.

"That is the tragedy. Guys that played in those great years have not been used to assist the development of South African cricket. Even today they could be used. To me, it just doesn't make sense when you see a guy even like Alan Donald working as a bowling coach in England. We should be using him for his great knowledge."

Does Pollock still like just watching cricket, surely one of the great pleasures of life for the sporting male? His reply surprises me. "I don't get the same pleasure. Cricket has become far too financial and I am not a 20 overs a game guy. If it wasn't for the big money, I'd be surprised if any of the guys said they enjoyed 20/20.

"It's a huge money making thing but it's just a slog and it's out of proportion to the game itself. I was talking to Barry Richards about it and he said, why not just have a bowling machine and see who can hit the ball the furthest.

"My concern is that 50 over cricket changed Test cricket because guys started to hit over the top. Once they start getting deeply into 20/20 cricket it will affect every other form of the game. I don't want to see a player get 50 in 60 balls in a Test match, there is a huge difference in the skills required to play the 5-day game."

Perfection for Pollock is a batsman setting out his stall, building quietly, gradually asserting his quality and then achieving dominance. "I like seeing a batsman dominate. You have plenty of batsmen (in world cricket) who can ensure their side doesn't lose but you need a guy like Kevin Pietersen, who can dominate to such an extent that he can change a game in two hours.

"The South African Test batsmen at the moment are workers, they grind it out. We have a lot of good discipline but we don't seem to have guys who can dominate, take a game away from their opponents."

I ask him what else he does in his life and am amused at his response. "I fiddle around."

Meaning? "A friend of mine is in the import/export business and I help him. I also had a coaching set up. But I'm not doing too much, I could be more involved. For a period of time, I was going over to the UK a lot. I had friends who owned a lovely house at Sunningdale (Berkshire) and we used to watch the golf. It was nice, I enjoyed that."

His frustration at not being able to impart more of his genius (my word, not his) into the minds of future cricketers is obvious. But he takes great solace in the myriad friends he has made in the game all around the world. He plays golf with Sir Garfield Sobers, one of his closest friends. "It was amazing how well received South African cricketers have been by players from the other countries. We were seen as reasonable people and we have had some fantastic times playing in world teams together."

And the future……..for Graeme Pollock and for his country? He sighs. "I don't have any particular personal ambitions, apart from staying healthy.

"But I do want to see South Africa become a merit country. No-one wants to be chosen just because they are a certain colour. They want to be there on merit. There are plenty of good enough non-white cricketers coming through and at the moment, they are there on merit which is good.

"Whoever plays, has to have pride in their country and we've got to come together to sort out our problems. We need all sorts of people who can make a contribution in many fields."

And will be Graeme Pollock be around to help, if required? "I wouldn't go anywhere, this is a fantastic place. I still have hope that people will see it that way."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks