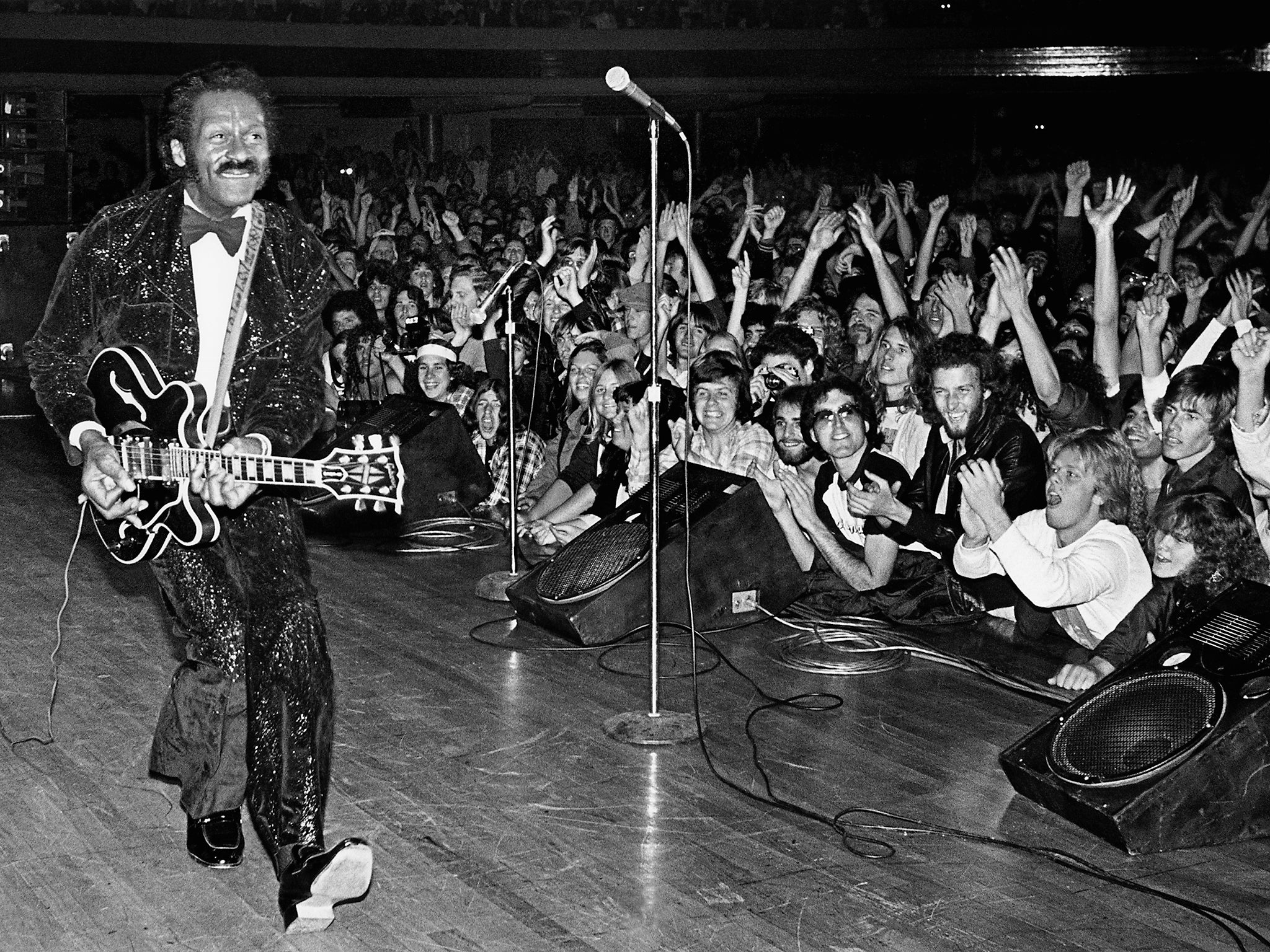

Chuck Berry was not always a nice man, but his music stood the test of time

He helped shake the world into looser, better ways, and explained the first real teenagers to themselves

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Rock’n’roll’s founders have been more physically durable than the 1960s rock stars they inspired. Until yesterday, Chuck Berry, like Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis, seemed an immortal embodiment of a mid-20th century cultural revolution whose shockwaves are only now subsiding. They’ll finally have to start carving a new Mount Rushmore, for these mighty remnants of a heroic age.

Elvis had the languid, likeable sexual swagger to lure segregated white audiences to his miscegenated music, Little Richard was the sexually transgressive, atom-splitting anarchist of hard rock’n’roll, and Jerry Lee the truly dangerous, untameable white wild child. Chuck Berry was this great generation’s equivalent to Cole Porter, Jimi Hendrix and Nat “King” Cole, in one tough, cantankerous skin.

Already 30 when he recorded his first hit for Chess Records, “Maybelline”, in 1955, he took an assessing, outsider’s look at the nascent teenage landscape, and became its first, sympathetic poet laureate. 1957’s “School Day (Ring! Ring! Goes the Bell)” is blues for schoolkids, working at a desk described like a factory shift, picked on by a bully in the desk behind, and yearning for 3pm escape to the freedom of loving and dancing to their private, new beat. “Hail, hail, rock’n’roll/Deliver me from the days of old,” Berry sings. “Long live rock’n’roll/The beat of the drum is loud and bold…”

Flip “School Day” over, and you heard the instrumental “Deep Feeling”, powered by Berry’s stinging slide-guitar, intertwined with the piano of his career-long collaborator Johnnie Johnson. Berry was indulging his deeper blues-playing instincts on this B-side. But his playing on the likes of the epochal “Johnny B. Goode”, relentlessly riffing with an awareness of swing rhythms, with black Rhythm & Blues roots but a light country twang, was its own, hugely influential school. Its driving, simplicity leapt like lightning from California’s Beach Boys to Kent’s Keith Richards, and found more basic, brutalist echoes in punk rock. The moment in Back to the Future when a Berry-like black rocker learns his moves from time-travelling white boy Marty McFly is one of Hollywood’s more thoughtlessly vile revisions.

Berry also mythologised rock’n’roll almost from its start, hymning its immortality against the adult nay-sayers who presumed it a fad. There have been doom-mongers from bitter old punks to rave revisionists who have been sounding the music’s death-knell ever since. Berry’s “Roll Over Beethoven”, “Rock And Roll Music” and “Johnny B. Goode” (and the latter’s sequel, “Bye Bye Johnny”) offered a sturdy, self-aware counter-argument. Long before Bob Dylan led a serious- and literary-minded counter-culture, Berry declared that the music he was making mattered, and that his young fans, sneered at as greasy juvenile delinquents, counted, too.

Berry was deliberately accessible to both white and black audiences. His patented “duck-walk” across the stage was showmanship without the shock of his peers, and the heavy influence of Southern country music and Nat “King” Cole’s croon softened the radical new facts of his lyrics and sound. But he had been jailed for attempted armed robbery back in 1944, and the law would regularly hound him, not helped by some unpleasant sexual proclivities.

He was off the scene, serving time, between 1961 and 1964, getting out to find The Beatles bringing his old songs to a new generation. But his final significant burst of hits in the early 1960s – “Memphis, Tennessee”, “Nadine (Is It You?)”, “You Never Can Tell” and “The Promised Land” – more than matched Lennon and McCartney in their sly wit, and double-edged assessments of an America which has treated so many of its black giants so pitilessly.

For all his faults, Chuck Berry made it through 90 years his own way, and finished his first album since 1979 just before his death. He helped shake the world into looser, better ways, and explained the first real teenagers to themselves. Flawed, yes, and not always nice. But he was a monumental man.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments