Child abuse needs mandatory reporting to create a high-risk environment for paedophiles

We are lacking the political will to change the current culture in which whistle-blowers are too frightened to speak out

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

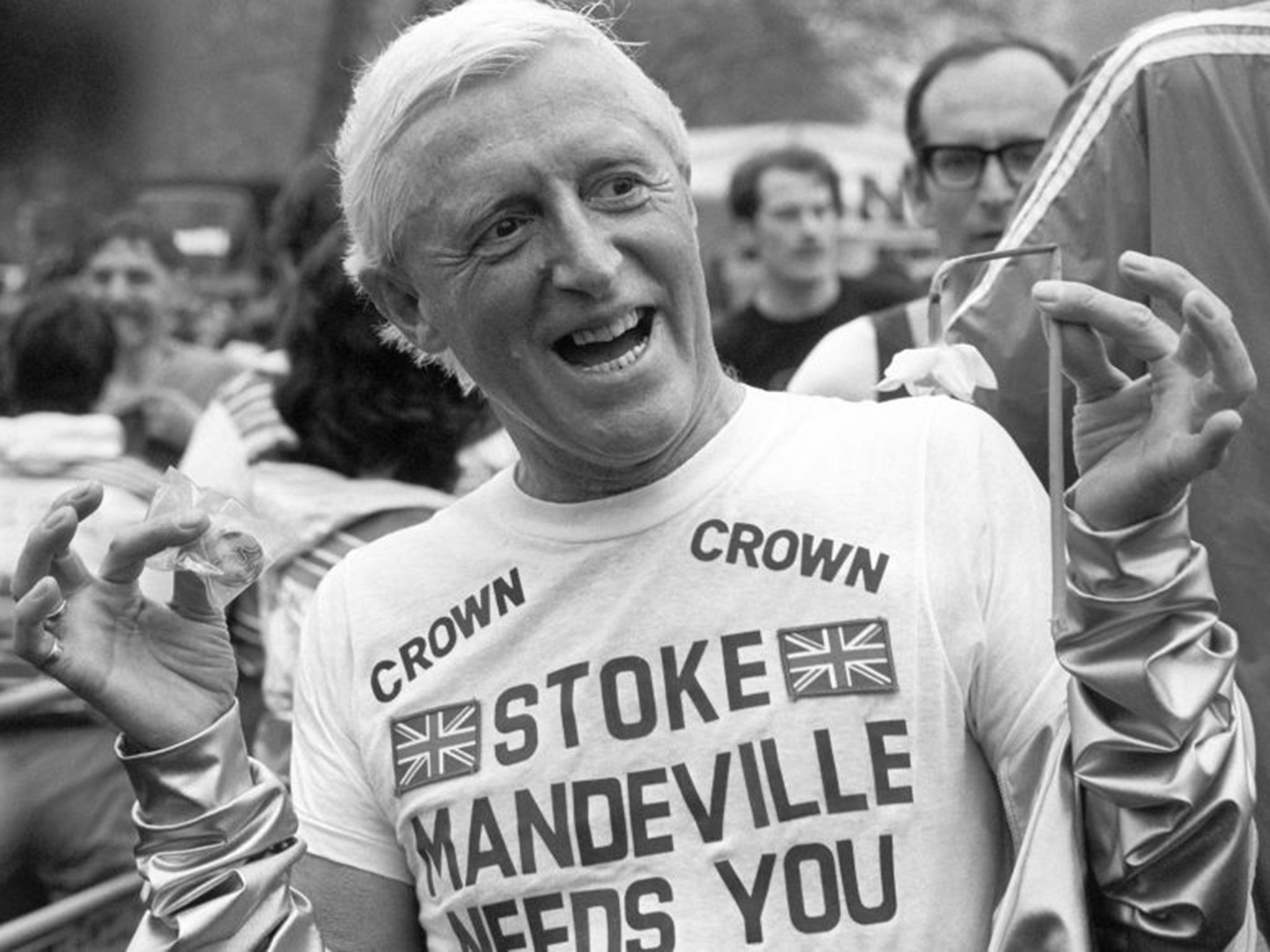

Your support makes all the difference.We have been here before, but last week’s further evidence about Jimmy Savile and his 63 abuse victims at Stoke Mandeville Hospital still had the power to astonish. Few of us can understand how it went unchallenged for so long. In the grand old British tradition, of course, no one is to blame. No one is to be held accountable. Worthy souls agree it is all very shocking, wring their hands and talk of lessons learned, but no one really pays the price for all those life sentences inflicted on children.

Bizarrely, we are told that hospitals are to tighten up on which celebrities are allowed to visit, but essentially the established professional expectation (amateurish, I’d call it) that people “will do the right thing” lives on. So what about all those people who “had their suspicions” but sat on their hands? I have a degree of sympathy with them, as it happens. It is extremely rare for someone to witness abuse as it is happening. To make an allegation about a colleague without chapter and verse requires a lot of courage. You acquire the tag of busybody, telling bad news to someone who doesn’t want to hear it. No wonder so many people “play safe” (a preposterous term in the circumstances) and give the benefit of the doubt. And so the abuse continues.

But if they were legally required to report on their concerns, the good guys would all be on the same side. Only one person, the abuser, would have reason to be fearful. Suddenly an institution where abuse exists becomes a high-risk environment for a paedophile. Isn’t that what we want?

It certainly is, and contrary to what some fear, it doesn’t risk creating witch-hunts. Giving Johnnie a hug in the playground after he has scratched his knee hardly gives rise to “suspicions on reasonable grounds”. That is the term used to require potential reporters of money-laundering to come forward, as spelt out in the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002. And it has had a remarkable effect, as the police can confirm.

Britain lags behind the world – appallingly so – on abuse. A large majority of European countries – 86 per cent – have some form of mandatory reporting (MR); 77 per cent of African countries do; 72 per cent of Asian countries and 90 per cent of the Americas do. It may sound radical and possibly slightly un-British in going against a “live and let live” ethos. Yet, in this context, isn’t that precisely what is needed? It would change the culture of so many areas of regulated activity (we are not talking about families here), and in the long run would go a long way to remedying a situation in which, by one credible estimate, only 5 per cent of sexual abuse is detected.

No decent person would want such a problem unsolved, surely. Yet, if you were a politician, would you be so keen once you have understood what it would take? In an age of short-termist careerism, for many of them it’s too much like hard work. So they content themselves with sticking-plaster solutions that give a nod towards addressing the cause but do no such thing. Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt warns of “unintended consequences” of introducing MR. It took me nine months to find out what exactly he was talking about, and I’m not impressed by what he claimed. Others say it doesn’t work, but that is based almost entirely on research into families, not schools, hospitals, churches, Scout groups and the other target-rich arenas that attract paedophiles. Many of those who oppose it are simply behind the curve and not au courant with recent research.

Australia is often cited by some as showing that MR doesn’t work, yet the number of allegations of abuse in institutional settings has now gone down to below where they were before it was introduced, while the number of substantiations from those referrals has risen. So, after a healthy weeding out – or at least scrutinising – of the guilty, the amount of abuse has actually declined. A requirement to report has removed the stigma of blowing the whistle.

The real reason for the foot-dragging is cost, I believe. There has been far more abuse than the authorities have acknowledged, but the truth is now dawning. Recently, Alison Saunders, the Director of Public Prosecutions, asked for an extra £50m to help the Crown Prosecution Service handle all the cases on its desk. The courts can’t cope – they simply don’t have time to deal with what is heading their way, and there are already eight prisons full of sex offenders. The Government will need to build a great many more if it is serious about taking this on. I have heard experts talk of public bodies being “swamped” with claims if MR is introduced. And what of holding those institutional leaders to account who walk away from known child protection “crash sites” with pay-offs and full pensions – the accountability gap?

There is a potential answer, though: the 1933 Children and Young People’s Act. Part 1, Prevention of Cruelty and Exposure to Moral and Physical Danger, seems to contain the levers to enable institutional administrators who fail in their statutory responsibilities to be held to account. In this context at least, it has fallen into misuse. There is no reason that I can see why it shouldn’t be used for countless cases I could mention. What is required is political will. And that is the problem. Considering the potential front-loaded cost, you’d be a frightened politician. But given that there aren’t many crimes worse than child abuse, that wouldn’t be good enough, would it?

Tom Perry is a survivor of abuse and founder of the group Mandate Now