£3m EU grant sends Kenyans switching from charcoal to cook instead on treated human waste

Demand ‘far outstrips’ supply of new cooking briquettes made from sewage blasted with high heat then mixed with molasses and sawdust

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The truck filled to the brim with human waste trundles to the sewerage treatment plant where a crew eagerly waits for the noxious commodity, ready to convert it into briquettes that will be used to fuel Kenya’s cooking fires.

The ambitious project is providing an environment-friendly solution in addressing sanitation challenges as well as conserving trees.This indeed is a bold move from Nakuru, Kenya’s fourth largest city 100 miles west of the capital, Nairobi.

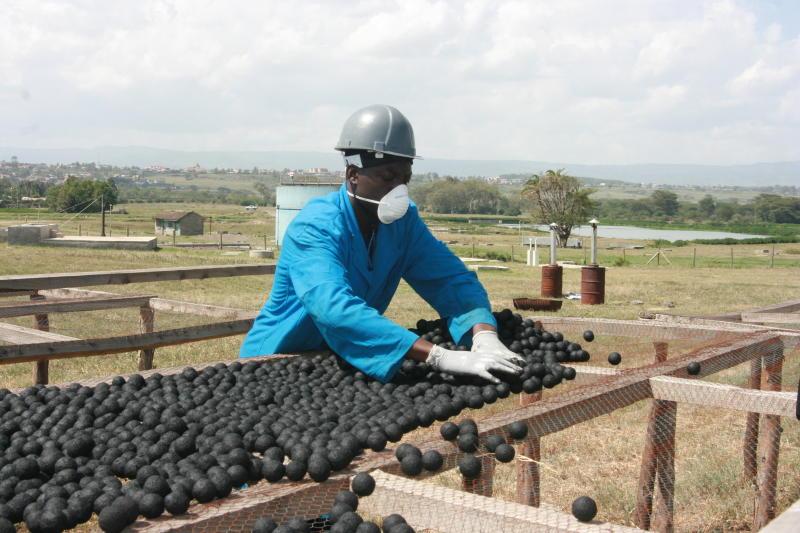

The briquettes, fondly referred to by locals as makaa-dot-com, are made by adding sawdust to the human excrement. And their popularity has shot through the roof.

“Demand is high, far outstripping the current production of three tonnes a month. We receive orders of over four tonnes daily, a need that has pushed us to upscale production to 10 tonnes a day,” James Ng’ang’a, managing director of the Nakuru Water Sewerage and Sanitation Company Limited told Kenya’s The Standard newspaper.

The project, which has received close to £3 million in European Union grants for innovative ideas that improve sanitation services, has grown in popularity following the logging moratorium and charcoal ban that is currently in place in Kenya, because it has shielded residents from the worst effects of the crippling charcoal shortage.

“A factory is ready and equipment has already been shipped ready for installation. Once done, we can be able to meet the demand and even supply to schools, factories and supermarkets,” Ng’ang’a said.

The Nawassco MD revealed that apart from the traditional consumers of charcoal, who were scrambling for alternatives, a large number of their customers were poultry farmers, who said they observed lower mortality rates among their birds when they used the briquettes to heat the chicken houses.

The project has also played a major role in controlling the amount of waste being channeled into Lake Nakuru - one of Kenya's most iconic lakes that is home to thousands, sometimes millions of flamingos.

“Lake Nakuru is a Ramsar Site and it faces a lot of challenges due to pollution. This project will reduce the amount of waste channelling into the lake even after treatment since most of the waste is used as raw materials,” Ng’ang’a said.

But before the briquettes find their way into the kitchen, they have to undergo several processes to ensure they are free from disease-causing pathogens.

“The process has been approved by [Kenya’s] National Environmental and Management Authority and the briquettes certified by the Kenya Bureau of Standards,” the project site manager John Irungu said.

Irungu elaborated on the manufacturing process, saying after the human waste is received at the site, the raw sewage is emptied into drying beds, where excess water is left to evaporate for nearly three weeks, leaving behind a solid residue.

The residue is subsequently exposed to high temperatures to kill any living organisms. Sawdust sourced from local saw millers is also heated up in a large pan – a process known as carbonisation.

Thereafter, the two products are mixed in equal ratios and ground into a powder. Diluted molasses is then added to act as a binding agent before the mixture is moulded into small round balls.

Mary Kerubo, a resident of Kivumbini, which neighbours the treatment plant, considers herself a lucky early adopter of the new commodity.

“As much as demand is high, we can always order ours directly at the site. It is very economical and we use very little compared to charcoal, which is even harder to source following the ban. I can use one packet of makaa dot com at least five times compared to charcoal, which I only use twice,” she said.

Reinilde Eppinga, a sanitation advisor with SNV Netherlands Development Organisation, which is a partner in the briquette project, said only 27 per cent of Nakuru residents are connected to the town’s sewerage system, highlighting the need for a better way to dispose of the large quantities of human waste generated each day.

This article is reproduced here as part of the Giants Club African Conservation Journalism Fellowships, a programme of the charity Space for Giants and supported by the owner of ESI Media, which includes independent.co.uk. It aims to expand the reach of conservation and environmental journalism in Africa, and bring more African voices into the international conservation debate. Read the original story here.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments