Cameron’s right to tackle prisons, but his answer is wrong

One problem with the debate is the simplistic juxtaposition of tough versus soft. In challenging this, Cameron is breaking new ground

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the final phase of his leadership, David Cameron dares to highlight one of the great scandals of our times: what happens in prisons and, equally important, what happens when prisoners are released.

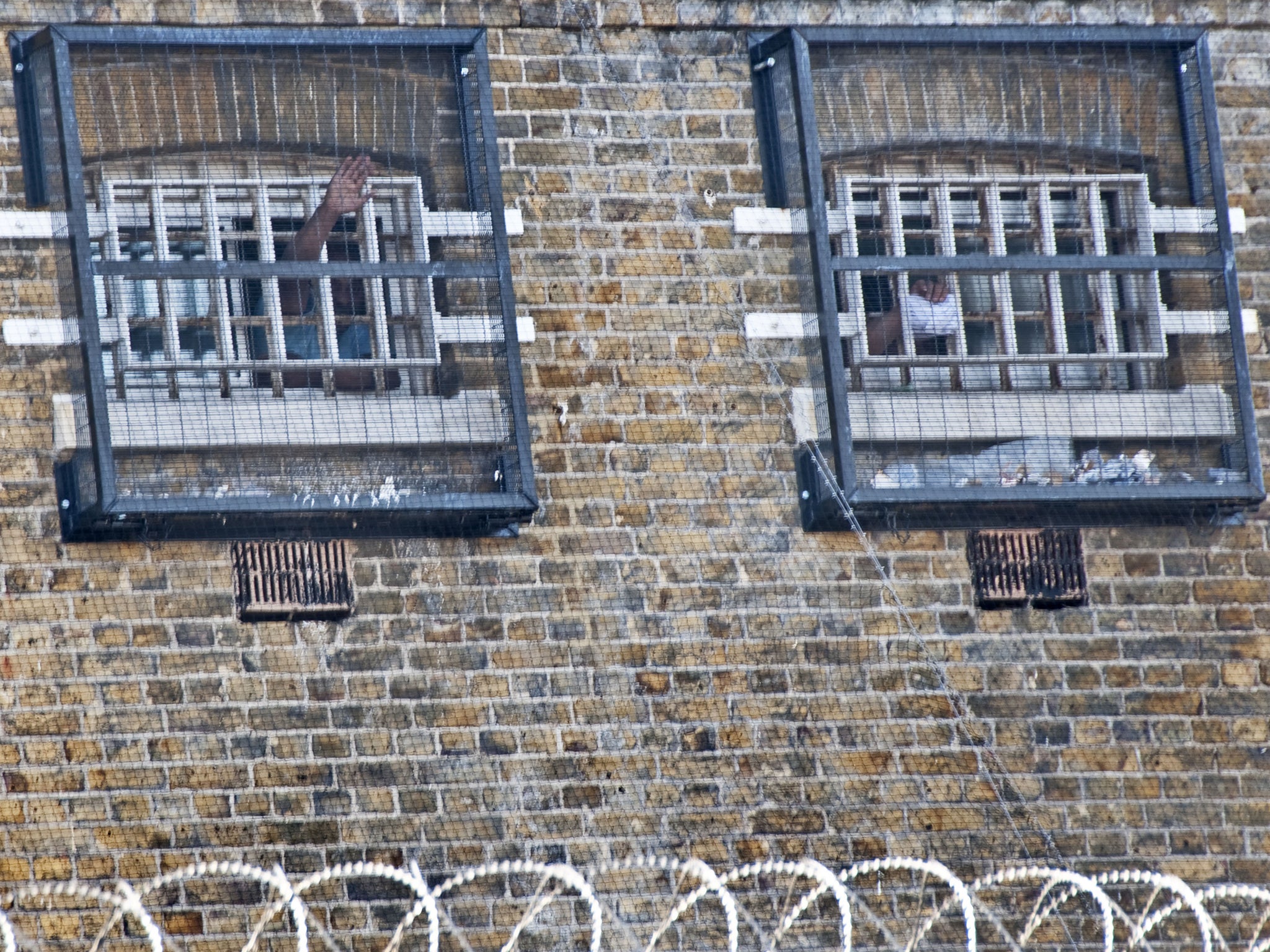

The context in which Cameron made his speech to the Policy Exchange think tank could not be darker. The prison population has doubled since Margaret Thatcher was in power, and she was not known for being “soft”. Now there are around 100,000 prisoners crammed into cells.

While the prisoners are incarcerated, the prisons float freely in a chaotic structure. How typical of modern Britain that there has been a political appetite for decades to lock up as many people as possible and yet no desire to address the wider anarchic context in which prisons are supposed to function. How typical of Cameron that he bravely and admirably breaks a taboo by insisting that the approach to prisoners must change, but does not fully address the issues of how prisons should be organised and resourced.

As Cameron notes, part of the scandal is that nearly half of prisoners reoffend when they are released. This is a mind-boggling statistic. All that taxpayers’ money putting offenders in cells and then they return to another crammed prison before very long. What is even more horrific is that the statistic has been known for a very long time. The scandal is both hidden, in that few live to see the inside of prisons, and at the same time right in front of our eyes if we choose to look. Some former Home Secretaries and chief inspectors of prisons have been trying to shine a light for decades.

In 2003, former chief inspector of prisons David Ramsbotham wrote a shocking book, Prisongate. Based on Ramsbotham’s own direct experiences, it highlighted forensically and vividly the nature of the scandal, the causes and the consequences. In some ways the most alarming section of his book relates to his discovery that there were no connections in the system, from the Home Office to the cell. During a visit to Holloway Prison, the women’s prison in north London, he was appalled at the filth, the poor quality of management, the presence of a large number of mentally disordered people and the shortage of staff. Subsequently, when he asked to see the director for women at the Home Office, he was told that the post did not exist and that no one on the Prisons Board had worked with women in prison.

Ramsbotham had been an army officer and was struck by the contrast between the clear lines of accountability in the army compared with the anarchy of the prisons. As I argued last week, in relation to the collapse of Kids Company, if the question is asked “Who is responsible to whom?” and the answer is “Well... it’s all a bit complicated” there is trouble ahead. Ramsbotham concludes: “There is an absence of responsibility and accountability. There is no director of women’s prisons, no director for children’s prisons, no director for ‘lifers’, no director for sex offenders. In short, no one in charge of ensuring the most modern management of very different categories of prisoners.”

Cameron’s answer is to give more autonomy to prison governors. Taken alone, this is a risky move and fails to address the wider structural issues. Because of the current anarchy, governors have inadvertent autonomy now – which is fine if they are good and disastrous if they are not up to the immense challenges. But Cameron adds some other good proposals that amount to forms of accountability based on the relatively successful introduction of school academies. He suggests league tables of prison performance, schemes to encourage graduate high-fliers to work in prisons and innovative ways to deter reoffending. Out-of-sight prisons could be badly run without anyone noticing. He envisages much greater transparency, a form of accountability.

Cameron deserves praise for making a speech in which he argues that prisoners must be seen as “potential assets to be harnessed”. This is subtler than the usual demand that virtually everyone should be locked up. No Labour Prime Minister or Home Secretary would have made the case in the New Labour era, paralysed by the fear of appearing “soft” on crime.

Part of the problem with the debate around crime is the simplistic juxtaposition of tough versus soft. In seeking to even challenge these assumptions a little, Cameron is breaking new political ground as a Prime Minister, even if more enlightened former Tory Home Secretaries like Douglas Hurd have been making this case for a long time. He also echoes an excellent speech on the issue from the Justice Secretary, Michael Gove, soon after the election.

But breaking new political ground is not necessarily the same as sweeping policy changes. Prison budgets have been cut when regional groups of prisons are needed to keep prisoners in local areas and to continue education after release, as well as work training and medical or substance abuse treatment. Such an overhaul was recognised by the then Home Secretary, Kenneth Baker, who proposed clusters of prisons in a White Paper, in 1991. Nothing happened.

Will action follow now? Evidently a determined Prime Minister and a resolute Justice Secretary are potentially a powerful force within Government. But Cameron is moving towards the final phase of his leadership and successors might feel obliged to show how “tough” they are on crime. For Cameron, time is running out and he proposes mainly incremental change. But he did not have to address this highly sensitive policy area. In highlighting the scale of the scandal he at least creates the space for a change of approach even if he is not the one implementing urgently needed new policies, structures and attitudes. A Conservative Prime Minister has made clear that, as currently run, prisons do not work. Given the reactionary nature of the debate on prisons, that is a lot of space to create.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments