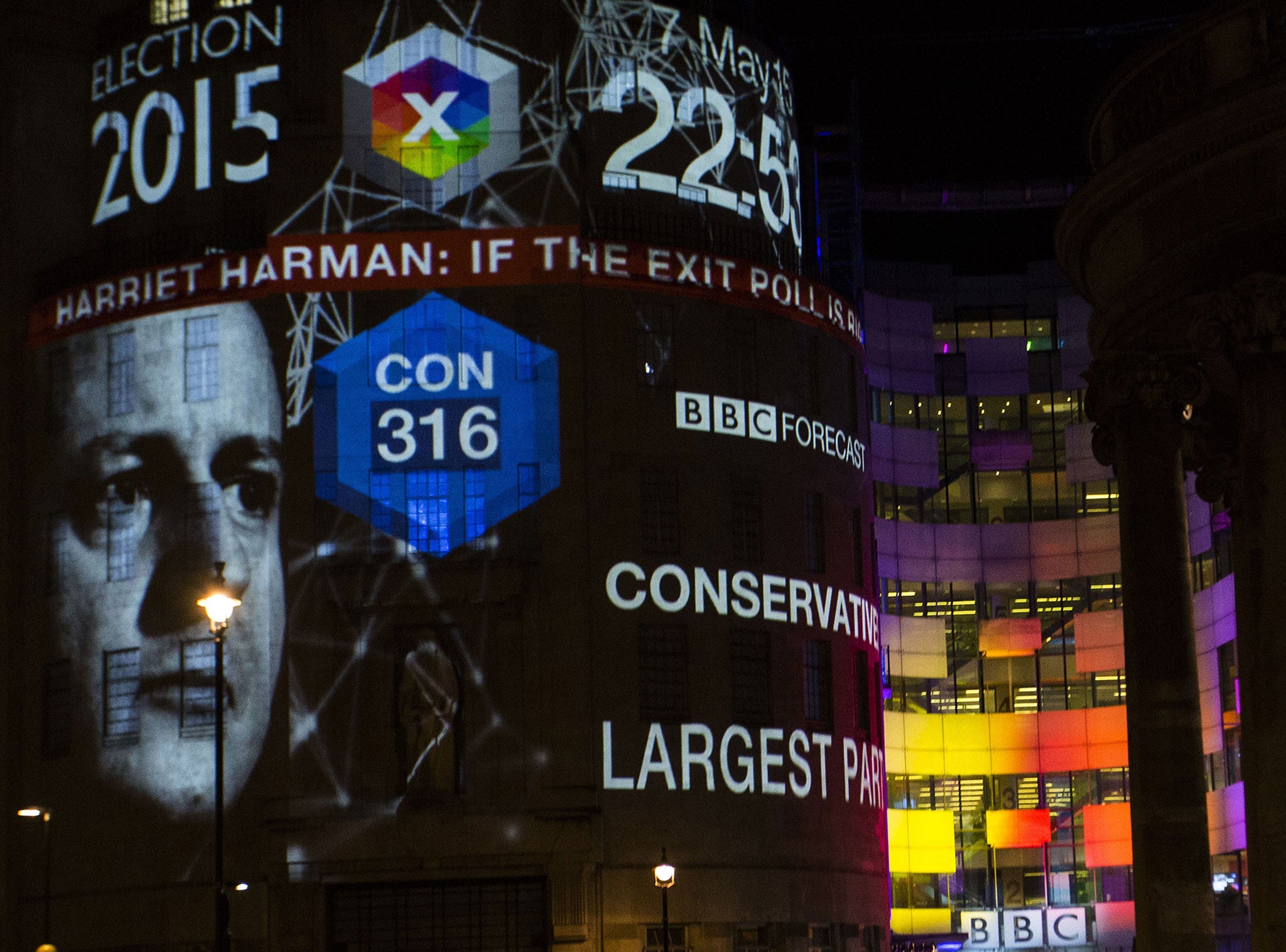

We used to be able to predict if people were Tory or Labour based on their wealth. Now it’s based on something else entirely

The old political certainties are turning: it is time we acknowledged what is staring us all in the face – the way people vote is increasingly about culture, not just economics

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I have spent almost my entire working life in politics and, for most of that time, I believed it could be explained by simple economic characteristics you could spot just by standing outside someone’s house.

If they had certain things like a higher income, a senior professional job, a marriage, good health, their own home – especially if it was without a mortgage and detached – they were more likely to vote Conservative. If they did not have any or many of those things, they were more likely to vote Labour.

This used to explain the age difference in politics too. Older people tended to be Tories because lots of those things tended to come with age. Younger people, who are less likely to have those things, tended to be Labour if they were anything at all.

But a few years ago, these old political certainties slowly began to turn. The axis has now rotated so far that it is time we acknowledged what is staring us all in the face: the way people vote now is increasingly about cultural characteristics, not just economic ones.

It is no longer just a matter of left versus right: “open” versus “closed” is becoming more and more significant.

These days, a far better way of predicting how someone will vote is to discover whether they live in an ethnically and religiously diverse area, the density of the local population around them, how they define their national identity, or what their feelings are toward minorities.

It means that lots of people who once were good bets to be Conservative now turn out to be Labour. And people that pollsters might have predicted would be Labour are now Tories.

The referendum on EU membership was, for most voters, not just about arguments such as whether they and their families would be better off. Instead, it was a stark choice between two fundamentally different reactions to the realities of globalisation: nationalism or internationalism?

A year later that same question was reflected in a significant churn in the base of support for both Conservatives and Labour. Millions of people found their attitudes more strongly defined by their feelings towards Brexit than by the offer from either party.

The political axis is rotating not just because of the referendum vote for Brexit, but because that vote connects to deep values that add up, for many people, to their whole world view. This explains why the gulf between Remainers and Leavers has tended to widen since the referendum.

Nor is this dramatic turn in politics merely a British phenomenon. Over the last few years, similar cultural questions have cut across traditional dividing lines in elections and referendums across the developed world from the US to France, Italy, Germany and Austria.

There has already been discussion about how Labour won among voters under the age of 47 in last year’s election, while the Conservatives won among people older than that. But this was not a story of the Labour vote share falling gently with age. Instead, it went off a cliff: the Conservative lead over Labour was huge among older voters – nearly 20 percentage points among 55-64s and nearly 40 points among over-65s; the Labour lead among younger voters was similarly enormous – around 30 points among those under the age of 45.

There has been much discussion of how badly the Tories did in 2017 among students. Again, this obscures the scale of the real story: the swing away from the Conservatives was even worse among 25-34s and nearly as bad among 35-44s.

I am not saying everyone who voted Remain or Leave also believes all or any of a set of propositions about globalism; it is that there is a high probability that they do. Lots of people reading this will have voted one way or the other in the EU referendum who don’t take an “open” or “closed” view on other issues. If that is you, congratulations: you are what polling firms call an “outlier”.

New polling for Global Future reveals that beneath this unprecedented generational divide lie profoundly different feelings about what the UK’s stance should be towards the rest of the world and about openness towards other people in general.

Under-45s overwhelmingly think that immigration and multiculturalism have changed Britain for the better. Over-45s are equally adamant they have made Britain worse. Younger people regard overseas aid and the EU as forces for good in the world, while older voters on balance see them as forces for ill. The younger group tend to the view that increased diversity has had a positive effect on the UK, while the older group see its effect as negative. The same difference in view applies to the right of free movement for EU citizens: by a margin of nearly three to one, under-45s regard it positively – while most over-45s see it as a negative. Three in five people in the younger group describe themselves as “globalist” or “internationalist”, rather than “nationalist”; the same ratio that takes the opposite view in the older group.

Across an array of value questions – gay marriage, feminism, measures to promote equality, human rights laws and social liberalism in general – there is a fundamental difference in world view between under-45s and over-45s.

Indeed, the rotation of the political axis from the economic divide of left and right towards a new open-closed divide can clearly be seen in the pattern of general election results over the last 20 years. The seats that Labour lost between its 1997 landslide and its 2010 defeat are concentrated in the parts of Britain defined by being non-diverse and relatively poor – the Brexit heartland also characterised by a concentration of “closed” values. And the voters that Labour lost over the same period were disproportionately likely to define their own national identity as “English” – or “Welsh” – rather than British.

The 2017 election showed a significant acceleration in this rotation of the political axis with the polarising reaction to the Brexit referendum being the most obvious cause. The average voter switching to the Conservatives was typically poor, left school at 16, working in a non-professional job and living in an area with little ethnic diversity – all of which correlates very strongly with holding “closed” attitudes. The average voter switching to Labour was better off, middle class, well educated and living in an area of high ethnic diversity – correlating with holding “open” world views.

In 2017 the Tory vote increased by about 6 percentage points across the country. But it barely rose at all – or even fell – in many of its traditional heartlands such as Oxfordshire, Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire, Sussex and Cheshire. At the same time, across England and Wales the Conservative vote increased most in traditionally working class Labour heartlands like South Yorkshire, Humberside, Cleveland, Durham, Tyne & Wear. Big though they were, these increases in Tory support weren’t big enough to win them many seats in 2017.

If this rotation of the axis continues, and in the current political climate there is no reason to believe it will stop, the Conservatives should expect to capture more seats in traditional Labour territory at the next election. But Labour too, has an opportunity to push on in “open” areas such as London, where the Tories lost six seats in 2017 and could lose another 10 at the next election.

Some of those MPs at risk in the Conservative Party will, of course, comfort themselves by thinking this gulf in attitudes is about the ageing process. Almost every teenager who ever expressed an interest in politics will have been told a version of the ancient – and patronising – line about younger people voting with their hearts and older ones with their heads.

But this gulf in values is nothing to do with the age of your body but a function of the fundamentally different worlds in which these two groups – open and closed – have grown up. People who are under the age of 45 now have been born since the early 1970s, have reached voting age in the mid-1990s or later and have spent their entire adult lives in the post-Soviet rapidly globalising internet era – the world of free movement of people, the age of Amazon, Google, Apple, a time of growing transparency and ever more openness. People who have only ever known these things are much more likely to accept them and see them as positives. People who remember the world before this economic, political and cultural upheaval are much more likely to feel insecure about the breadth and pace of change.

There is no good reason to believe the generation that has come of age in the last 25 years is going to change its world view as it grows older. Those whose life experience has led them to feel positive towards immigration, multiculturalism and internationalism are not going to suddenly reverse these positions when they get into their 50s and 60s. Their open world view is baked in; it is not a function of life-stage.

This means that while the gulf in values will continue, the age when open voters outnumber closed voters – currently at around 45 – will rise as the open generation gets older and the closed generation dies out.

Global Future is a new think tank making the case for immigration, free movement and an open and vibrant Britain. Andrew Cooper, a Conservative peer, is a member of its advisory board.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments