Forget the class divide, voters now cast their ballots over Brexit – and Labour is the loser

We are entering a new era in which voting is influenced by cultural attitudes, and it's a shift that helped put Donald Trump in the White House

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The mood at the Christmas party for Labour members of the Scottish Parliament was hardly improved by a presentation just beforehand showing that things for the party north of the border can only get worse. Internal polling suggested that Labour’s last bastion of support in Scotland in local authorities could crumble in May’s council elections. The SNP is on 45 per cent, the rejuvenated Conservatives 25 per cent and Labour just 15 per cent.

Labour's already weakening grip on its once solid Scottish base was broken by the 2014 independence referendum. The SNP lost, but won many Labour voters, landing 56 of Scotland’s 59 seats at the 2015 general election. Now despairing Labour MPs wonder whether the EU referendum will have the same devastating effect in England, as the forces of nationalism again transform the electoral landscape. It might be happening more subtly than in Scotland, but it is certainly happening.

Three recent parliamentary by-elections showed that Brexit is the new dividing line. In Witney, the Tories held on but the anti-Brexit vote was hoovered up by the Liberal Democrats, who achieved a 19 per cent swing while Labour’s support dropped. In Richmond Park, the Lib Dems ousted the Tory Brexiteer Zac Goldsmith with a 21 per cent swing, as Labour’s vote disappeared. In Sleaford and North Hykeham, the Tories comfortably retained a safe seat but Labour dropped from second to fourth place behind Ukip and the Lib Dems, whose share of the vote rose from 5.7 per cent in 2015 to 11 per cent.

The results confirm a continuing trend spotted by academics working on the British Election Study, who found before and just after the June referendum that voters’ political identity was shaped more by Brexit than their traditional party allegiance. It suggests we might be entering a new era in which voting is influenced more by cultural attitudes (such as those towards immigration) than by class – a shift which also helped Donald Trump reach the White House. Will it prove a temporary effect? I doubt it, since Brexit will dominate UK politics for years, and certainly until the next general election.

Labour looks certain to be the big loser. The party already had an electoral mountain to climb, because of its collapse in Scotland and boundary changes that will give the Tories an estimated 20-seat advantage.

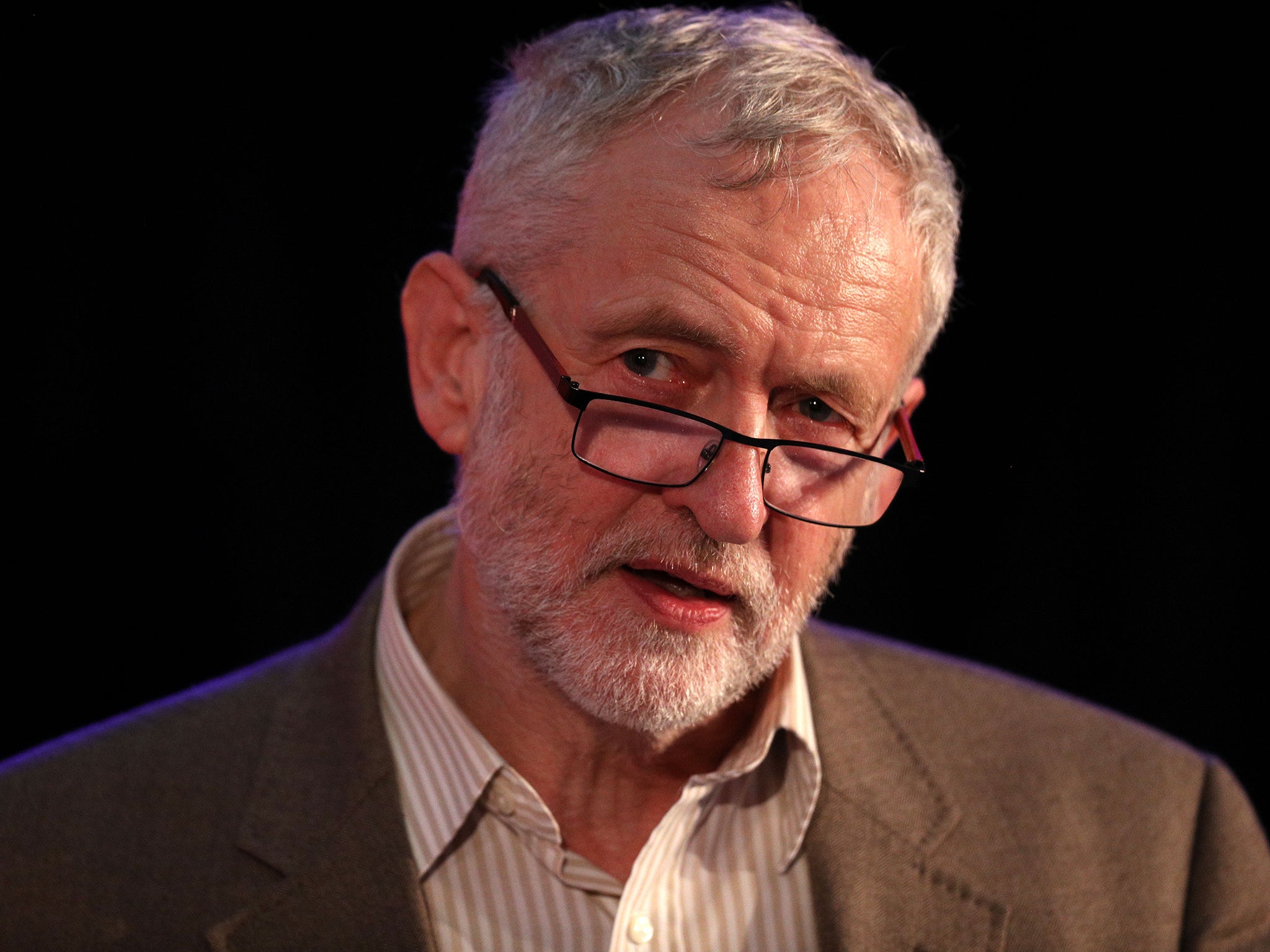

Brexit makes Labour’s climb even steeper. The danger is that the party appears irrelevant on the biggest challenge facing the country. Labour will struggle to win the confidence of both Leavers, because officially it backed Remain, and strong Remainers, angry about Jeremy Corbyn’s half-hearted referendum campaign and with a new champion in the Lib Dems, who unashamedly target “the 48 per cent”.

Strong Remainers will find little comfort and joy in Corbyn’s New Year message. He promises not to “stand by” while the Tories make a mess of Brexit, but equally insists that Labour accepts and respects the referendum result and “won’t be blocking our leaving the EU”.

His words sum up Labour’s acute dilemma. Almost 70 per cent of Labour-held constituencies voted Leave, so the party would provide Ukip with booster rockets by fighting Brexit. The Tories would love it too, accusing Labour of “defying the will of the people”.

But by sitting on the fence, Labour risks being squeezed out by Ukip and the Tories on the one hand and the Lib Dems on the other. Brexit also makes it harder for Labour to forge the coalition it always needs to win power – between its middle-class supporters who largely voted Remain, and its working-class voters who are more likely to be Leavers.

Labour’s response to the Brexit vote has been appalling. First Labour MPs played the man by trying to oust Corbyn; I can find no Labour figure who now thinks that was a good idea. Labour maintained a virtual radio silence on Brexit for three months. The Opposition finally started to oppose when Sir Keir Starmer was appointed shadow Brexit Secretary.

Starmer’s pitch, that Labour is the only party capable of uniting the country after the age, class and regional divisions exposed by Brexit, sounds clever enough. But Labour’s own divisions on the issue undermine its attempt to get in the game. The party cannot speak with one voice on immigration, with Corbyn rejecting growing demands from Labour MPs to end the party’s support for free movement. John McDonnell’s remarks about Brexit’s “enormous opportunities” hampered Labour’s appeal to “the 48 per cent.” Its challenge in 2017 is to reach them by mounting strong and credible opposition to a hard Brexit.

In any case, Labour’s playing the unity card will be trumped by Theresa May, who acknowledged in her Christmas message the need for people to “come together”. May is in a stronger position than Labour to unite the nation because she can act on her pledge and, as a reluctant Remainer now implementing Brexit, is better placed to appeal to both sides of the new divide in British politics.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments