If we make post-Brexit trade deals with China and India, don’t expect Britain to come out on top

Britain’s current crop of ministers seem not to have taken on board that the attempted EU-India agreement foundered not because of the rest of the EU but, in substantial part, because Britain rejected it

A key argument of those who see opportunities, rather than costs, in Brexit is that there will be better trading opportunities with the big emerging markets, notably China and India, than is possible as part of a 28-member EU. However, the probability of such beneficial bilateral deals is lower than Brexiteers might like to think.

The Chinese government was deeply shocked by Brexit and the Chinese do not like shocks. They are embarrassed by having invested so much political and financial capital in the UK only to see it veer off in a totally new direction without, apparently, any preparation or contingency planning. All their suspicions about the dangers of Western democracy have been confirmed in spades.

The UK split with the EU has also cast a very unexpected and dark shadow over President Xi himself. A successful UK-China free-trade agreement would help to repair the damage provided China is seen to be securing its key negotiating objectives. These objectives have to be understood in the context of the Chinese leadership having gone out onto a limb, promoting the UK ahead even of Germany. That prioritisation was dictated not by sentiment but a hard-headed calculation that while Germany has been important for providing capital goods and manufacturing technology, the UK is more useful for the next stage of Chinese development: a shift to a service based economy; the move to currency convertibility via Renminbi trading in the City of London; absorbing and welcoming Chinese investment (while not asking for reciprocity); and acting as a cheerleader for Chinese ambitions in global governance, as with the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

In the ancient Chinese philosophical tradition, a crisis is synonymous with an opportunity. A pending Brexit provides an opportunity to reset a more grounded relationship with London. So what does that entail? China is very clear what it wants. First, the UK should give strong support for China’s “market economy status” in the World Trade Organisation, protecting China from tough (US and EU) trade-defence measures.

Second, the UK should continue to provide a secure home for investment, providing opportunities (preferably with continued access to the EU single market) for Chinese companies, without the resistance encountered in continental Europe and the USA.

Third, potential confrontation over trade with the USA under President Trump will necessitate alliance building with Western powers more committed to the principles of free trade and multilateralism, like the UK, though not at the expense of relations with the EU.

Both sides have interest in coming to an agreement but Britain needs China to sign a piece of paper with a trade deal more urgently than China needs Britain. China has time on its side and a weaker negotiating partner.

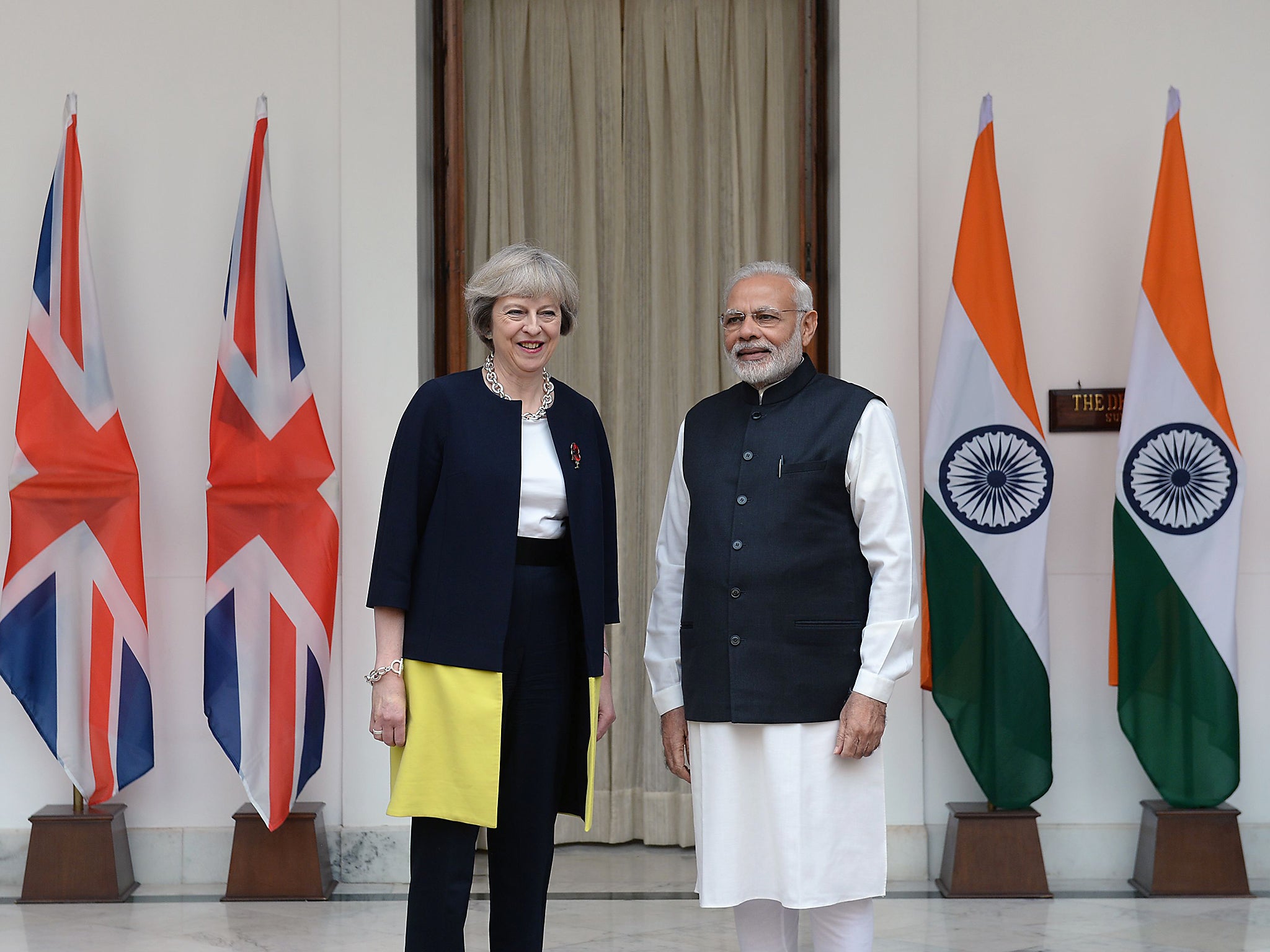

The fact that Theresa May chose India for her first serious foray in trade diplomacy signalled an eagerness to do business with the other Asian giant. India, however, approaches any bilateral negotiation from a position of strength. The sight of the former colonial master coming cap in hand will whet Indian appetites for a deal in India’s favour.

Moreover, Britain’s current crop of ministers seem not to have taken on board that the attempted EU-India agreement foundered not because of the rest of the EU but, in substantial part, because Britain rejected it. India also exports services, like Britain, and in the form of people. Attempts to open the UK to more Indian IT specialists and other professionals (the so-called Mode 4) foundered on the objections of the former Home Secretary, Theresa May.

The main irritant in UK-India relations is visas. In the absence of creative ideas on freeing up immigration and visiting rights from India, ministers will continue to get a flea in their ear in Delhi. And nothing is more irritating (and incomprehensible) to the Indians than Britain’s self-harming and very silly policy of counting overseas students against the immigration total; the services of our universities are amongst the few British products Indians actually want to buy. For these reasons Theresa May appears to have come away empty handed.

Failing agreement on these sensitive and difficult issues the Indians will ask for something else. Weapons? Something else Britain is good at, but they affect the power balance in south Asia and relations with Pakistan. Taking India’s side on Kashmir? Tricky.

The idea of Britain “taking back control” and rediscovering its former prowess in trade amidst the riches of the Orient is a tempting vision-from a safe distance. Ministers may soon wish however that they were more careful about what they wished for.

Sir Vince Cable is a professor in practice at the London School of Economics’ Institute of Global Affairs, a former Secretary of State for Business and president of the Board of Trade. Dr Yu Jie is a Dahrendorf senior research associate at LSE Ideas

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks