Why trigger warnings for books are infantilising and silly

Time was when the most dangerous hazard in an academic library was the arsenic used in Victorian cloth bindings. As Cambridge university audits its shelves for titles that might be ‘harmful’, Oxford professor Kathryn Sutherland wonders: who gets to decide what’s poisonous and what’s not?

Bad ideas sometimes come from good places, but sometimes the place too is bad. What are we to make of the memo reportedly sent to Cambridge academics by the University Library, asking them for titles of books that might be considered “harmful/offensive” and not just “in connection with decolonisation issues”?

The stated intention is to compile a list to help librarians “obliged to work with such materials” and to enable them to “better support readers”. The wording is solicitous, the unseen dangers lying in wait for both librarians and readers can be controlled, it is implied, with due diligence.

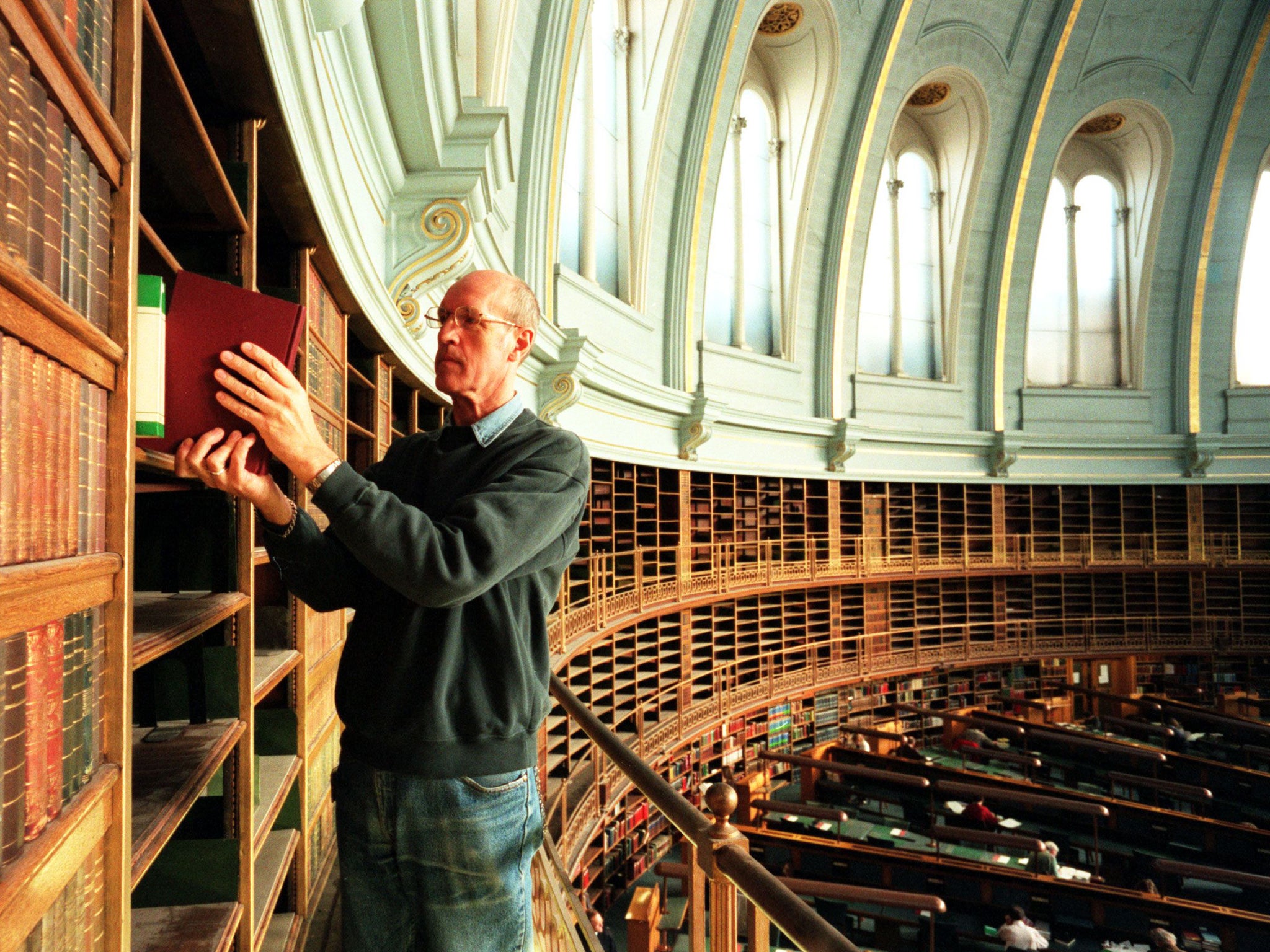

Who would have thought that librarianship entailed such risk? Here’s a telling little aside. In 2019, the Poison Book Project was set up to address the “hidden hazard” in library collections: specifically, arsenic in Victorian cloth bindings. The International Institute for Conservation recommends staff handling such books to wear nitrile gloves and to wash their hands.

Leading the project, Winterthur Library in Delaware also advises removing books from general circulation into a rare book collection, and that they be inspected on hard surfaces that can be wiped down and not laid upon soft furnishings where harmful traces might embed themselves.

There are scientific tests to quantify arsenical deposits in book covers, agreed protocols for handling, and a publicly accessible database listing hazardous copies. But what criteria might be employed to measure as “harmful/offensive” what goes on inside a book – its ideas? A smidgen of misogyny? A smattering of racism? A whiff of colonialism? A tidal wave of violence? Who decides, for whom and why?

Since the 1970s, English literature has been hugely enriched by the reintroduction of writings by women, many of whose voices had been silenced for hundreds of years. The more recent visibility of Black writers has begun to reverse mainstream Western culture’s imbalanced representation of society. But these initiatives are about widening the bounds of approval. Our culture fashions our identities; the more diverse, antithetical, contradictory, even antagonistic, the less we limit our growth as reflective, adult human beings.

Trigger warnings, on the contrary, are infantilising and silly. The actions of bookstores that refuse to place controversial material on display – or, more likely, individual members of staff who take it upon themselves to ‘demote’ from view paperbacks they consider problematic – are chilling. Pointless or pointed, such finger-wagging too easily accommodates our narrowed, Twitter-length attention spans, encourages binary thinking or thinking’s total absence, and threatens responsible and compassionate adulthood.

In a scene towards the end of Charles Dickens’ Bleak House, the lawyer’s clerk Mr Guppy, renewing his comical attempt to win the hand of the heroine Esther Summerson, brings his mother along. The meeting takes place in the home of Mr Jarndyce, Esther’s guardian. When her son is again and inevitably rejected, the affable Mrs Guppy turns nasty, rounding upon Mr Jarndyce with the demand that he leave the house: “‘Why don’t you get out?’ said Mrs Guppy. ‘What are you stopping here for?’ ‘My good lady,’ returned my guardian, ‘it is hardly reasonable to ask me to get out of my own room.’”

Presumably Cambridge University Library has sent its enquiry to every academic – to mathematicians, to medics and physicists? But it is not unreasonable to speculate that its weight will fall heaviest upon the humanities, those bookish subjects like history, philosophy, ancient and modern literatures, whose teachers are effectively being asked, one by one, to take themselves into moral and political custody. Like Mr Jarndyce, they are presented with eviction from their own territory – in this case, a space for nuanced thinking about shades of meaning and opinion in a world that demands more from us than easy condemnation or virtue signalling.

Walter Scott, Robert Louis Stevenson, Rudyard Kipling and John Buchan wrote hugely popular colonial romances, now no longer fashionable, but should we add them to the list just in case they threaten a return?

What about Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park? Or is it enough that the suggestion of colonial exploitation is rendered problematic within the novel’s frame?

And speaking of Austen, I’ve always found troubling that scene in Emma – the bit where Mr Knightley, having proposed and been accepted by the heroine, tells her he fell in love with her when she was 13 (at the time, he was 29), and she, promising always to call him Mr Knightley, in turn teases him that he must not fall in love with the village’s newest addition, a baby girl, when she turns 13. Would I place a warning on the passage, or have the book taken into special library protection?

Of course not. We should not assume that, offended in reading, we are thereby damaged or infected – a kind of reverse bibliotherapy.

Universities must promote open and free debate. We should not be in the business of fuelling intolerance, of no-platforming those views we find objectionable. To ask academics to submit books into a category labelled “problem” is to ask us to abdicate a responsibility that lies at the core of what universities are for: spaces for growing up, rather than growing less.

May I politely suggest to the Cambridge inventors of the problem book list a title they should read: Umberto Eco’s bestselling novel The Name of the Rose. At the heart of its web of suspicion, secrecy and power lies a labyrinthine library whose keepers guard the one remaining copy of a lost work, its pages laced with poison as further deterrent against reading.

The book is Aristotle’s treatise on laughter.

Kathryn Sutherland is emeritus professor at St Anne's College, Oxford

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments