Bob Dole showed how disabled people could live full lives – for good and for bad

He lived at a time when disabled lives weren’t valued, so he built ways to include them. I benefited from that. How does his support for Trump square with that?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As a young man, Bob Dole was a student athlete who briefly played for the University of Kansas’s football and basketball teams, even playing briefly under Phog Allen, one of basketball’s founding fathers. In another world, he would have maybe stayed there. Perhaps he would become a revered athlete when the NBA was launched in 1946.

But after the bombing at Pearl Harbor, the call for service came and he enlisted in the Army Reserve Corps and went into active duty in 1943, which would change his life forever. In 1945, in the small Italian town of Castel D’Aiano, Nazis fired on Dole’s platoon and as he stopped to pull his comrade to safety, flying metal shattered his right arm.

In a world that sees disabled lives as less, many would say his life would have been over. But rather, as he recovered, he was already planning his next step. As he recovered next to Daniel Inouye, a young man from Hawaii who had his arm blown off fighting the Nazis, Dole talked about going to law school and then running for Congress. That piqued Inouye’s interest and he arrived in Congress as a Democrat two years before Dole arrived on Capitol Hill.

When he got to Congress, Dole made disability rights a focal point. During his maiden speech in the United States Senate in 1969, Dole talked about the ableism that often limits people with disabilities as much if not more than their disability ever did.

“Exclusion – maybe not exclusion from the front of the bus, but perhaps from even climbing aboard it,” Dole told his colleagues on the anniversary of his injuries. “Maybe not exclusion from pursuing advanced education, but perhaps from experiencing any formal education; maybe not exclusion from day-to-day life itself, but perhaps from an adequate opportunity to develop and contribute to his or her fullest capacity.”

Along with championing civil rights for others – he voted for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and along with supporting the Voting Rights Act in 1965, negotiated its reauthorization in 1982 with Ted Kennedy – Dole helped to change the world for the better for people with disabilities and made their lives freer. He helped pass the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which prohibited discrimination for people disabilities by federal agencies and programs receiving federal assistance, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, and the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Most notably, Dole made these strides while collaborating with politicians from all stripes, like his occasional rival in GOP presidential primaries George HW Bush, the liberal Ted Kennedy and conservatives like Orrin Hatch and Senator John McCain, who was disabled from his injuries from being a prisoner of war in Vietnam (Dole wore McCain’s POW bracelet as a United States Senator while McCain was in the prison known as the Hanoi Hilton).

I know how much the world changed because I lived in the world Dole helped build. I was born the year the ADA was passed and as a disabled American, I grew up knowing I had rights and I belonged in this world. Their work was far from complete and disabled people constantly have to fight for their rights and face onerous legal challenges. But the spirit of independence and liberty that serves as the impetus for those fights was encoded in the laws he helped pass. And those ideals are the best examples of what compassionate conservatism can do; they don’t ask for the government to do things for them as much as they ask for the law to treat them fairly and afford the same opportunities that abled people are guaranteed.

Unfortunately, the GOP drifted away from that spirit. It would be easy to say it was simply a product of Trump – and make no mistake, Donald Trump is perhaps the most ableist president of my lifetime. But the Republican Party’s shifts long preceded them. The Voting Rights Act that Dole supported was gutted by a conservative Supreme Court in 2013 and there are little to no signs of a cavalry of pro-democracy Republicans jumping on board to save it.

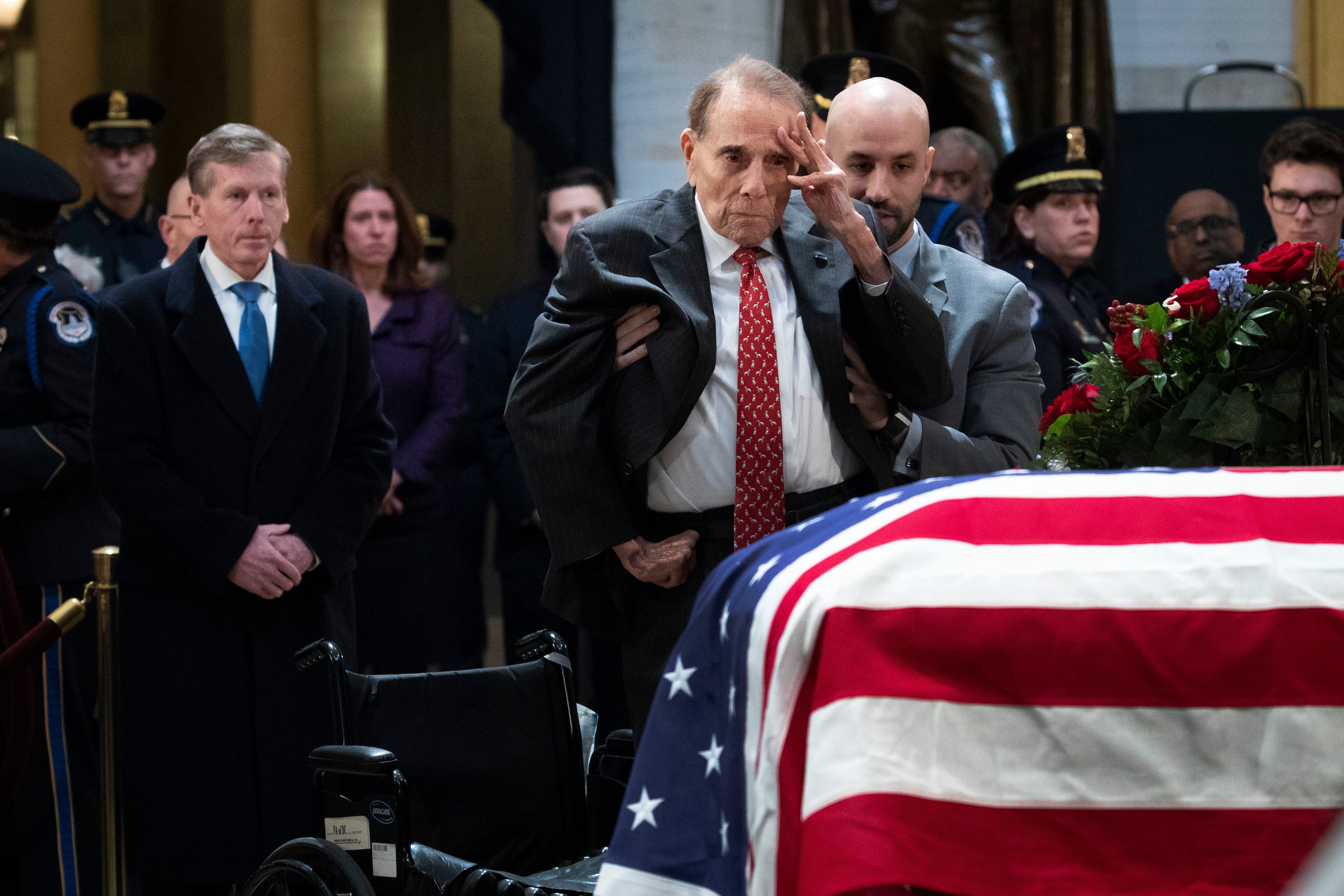

Similarly, when Dole returned to the Senate to convince Republicans to support the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, a United Nations treaty that would have defended the rights of people with disabilities across the globe, he even lobbied his former colleagues on the floor, only to see it die on the very floor where he had given that first speech.

But despite his laments that his party was going too far to the right, he also was the only former GOP nominee to attend the 2016 Republican National Convention, despite the fact Trump had shown nothing but contempt for disabled people. Even after the Capitol riot, he said in an interview with USAToday in July, “I’m a Trumper,” before adding “I’m sort of Trumped out, though.”

It’s that dichotomy that proves incredibly frustrating. Dole had spent a career trying to build a better world for disabled people, only to end his public career by the side of someone whose pandemic response disproportionately endangered disabled people (to say nothing of the fact Dole willingly signed up to defend his country and in a war that fundamentally altered his body as a young man while Trump found an excuse to not go to Vietnam).

It would be easy to say that one negates the other; to say that Dole’s work supporting Trump nullifies his advocacy or that his support for people with disability rights trumps (pun absolutely intended) his support for a right-wing demagogue with little regard for democracy.

But that is too simplistic. Rather, Dole’s life and career show that disabled people aren’t the saints that they are often portrayed as being. Their lives and rationales for voting and not voting in certain ways are difficult for us to understand. In short, Dole was human and experienced it, for all its glorious peaks and its great blunders. And that means he led a full life, something we still don’t think is possible for disabled people.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments