Attending an all-Black church school changed me for the better

We were happy, engaged, vibrant, neat, well-moisturised, melanated beings – that in itself meant that we were unwittingly subverting stereotypes in a cruel unforgiving world

Attending an all-Black church school positively moulded me into the woman that I am today.

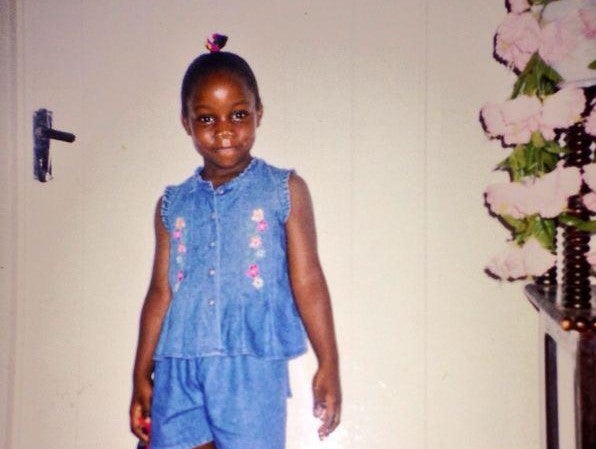

The experience initially came as a shock to my sensibilities as a young girl who was used to existing within spaces in which I was “other” and stood out as opposed to blending in.

It was 2001, I was eight years old, attending our local, predominantly white state school in south London. There were Black and Asian children, but we weren’t the majority, and Black teachers were even fewer and further between.

Don’t get me wrong: I was comfortable at this school. I’d been attending since reception and had friends. I was popular, the lunches weren’t too terrible and it was a stone’s throw from my darling Nana’s house where we spent much of our time.

Sure, teachers had a tendency to complain to my mum about what they would call my “outbursts”, a euphemism for the colourful expressiveness common among our demographic. Often, Black children are labelled as “naughty” for just being themselves.

Plus, very few people looked like me – with my dark skin, broad nose and high cheekbones – but school represented all I knew in terms of life outside of my home and beyond the Seventh Day Adventist church I attended regularly.

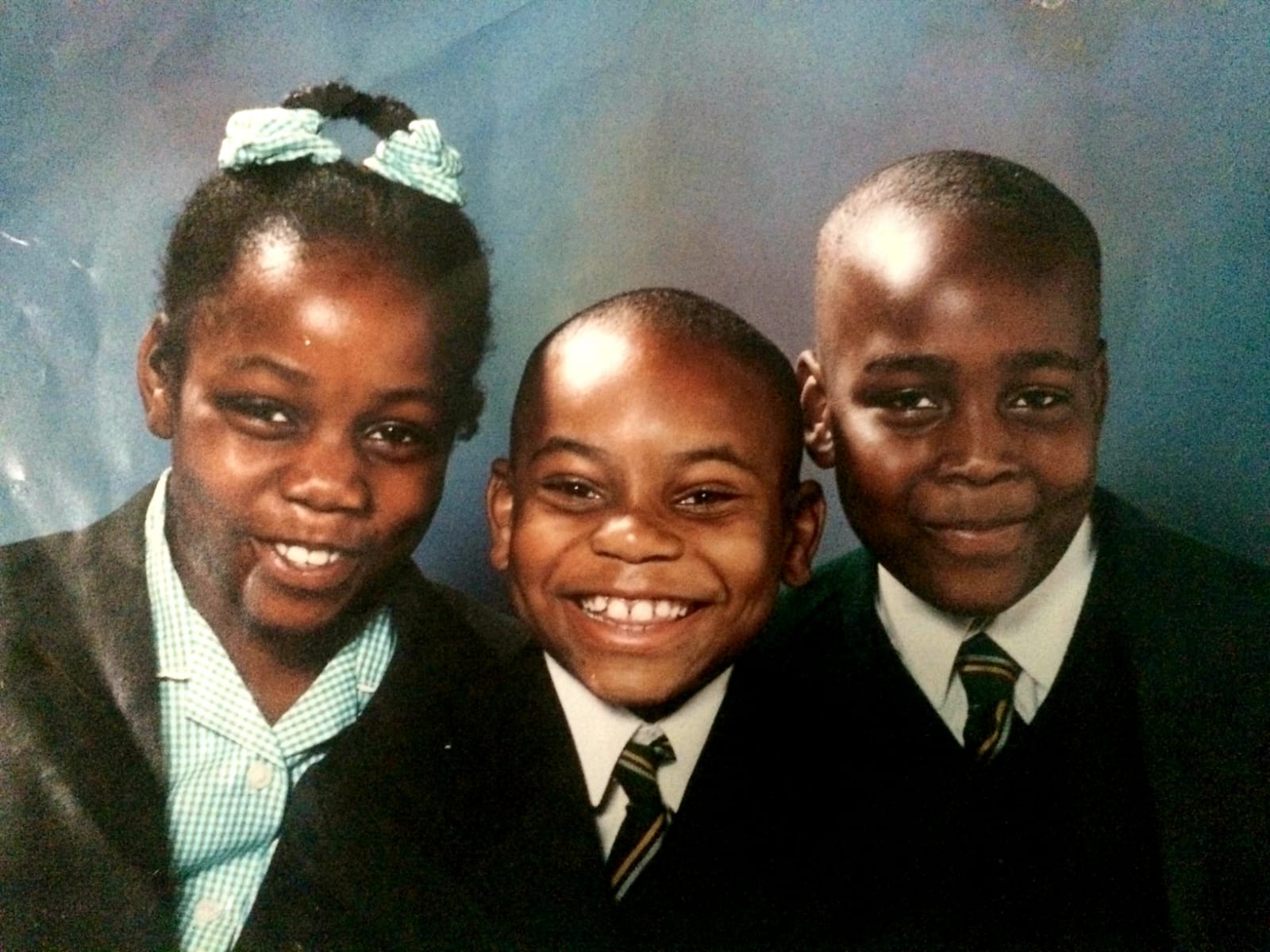

At the end of one fateful day, I skipped out of the school gates and jumped into the car with my mother who informed me that I, along with my brother Ishmael and cousin Jordan, would never be attending that school again. In no time, it seemed, we pulled up outside Brixton Seventh Day Adventist church, just off Acre Lane. Baffled, I turned to my mum and asked: “Why are we outside church?”

I soon learned this was to be my new school. Theodore McLeary Primary was run by formidable, no-nonsense Jamaican headteacher Mrs Thompson and staffed by equally upright Black teachers.

I realised that my trusty church was home to an institution that was part of a network of Adventist-run schools scattered across the UK. All members of staff could have easily passed for my aunts and uncles. They looked like us, spoke like us, walked like us and talked like us.

Theodore McLeary was a fee-paying, independent school and my parents – a mechanic and nurse – worked multiple jobs to cover my and my brother’s places at the school. No more than 40 children, all Black, were pupils while I was there.

The lunches were distinctly Jamaican with British influences, and here, many of us young Windrush descendants didn’t have to trade in one aspect of our being for another.

We sang uplifting Caribbean tunes during assemblies and said prayers before lunch. Our Christmas nativity boasted reggae and calypso scores.

Cautionary old Jamaican proverbs were drilled into our heads on a regular basis, the same ones we’d often hear our relatives utter.

Theodore was based on a grammar school model where the three Rs – “reading, ‘riting and ‘rithmetic” – were king. Punctuality was a must and we were taught to have pride in our presentation, defying the negative perceptions perpetuated about young Black people as being naughty “ragga-muffins,” as one of the teachers would say.

No, we were respectable young ladies and gentlemen; we had bright futures ahead of us, we were frequently reminded. “Have pride in yourselves,” we were told, time and time again.

I fondly recall the headteacher inspecting our shoes, which had to remain unscuffed. It was at Theodore McLeary where I learned the trick of rubbing an old pair of tights to shine loafers if you’d ran of shoe polish.

At my previous school, I had become accustomed to performing, acting up as the class clown to be liked, while having to police my tone for the predominantly white, middle-class teachers. I left all recognition of my cultural norms at the playground gate every day.

Upon reflection, I realise that in that space, I was only able to be only half of who I was, which is a lot for any child to have to negotiate.

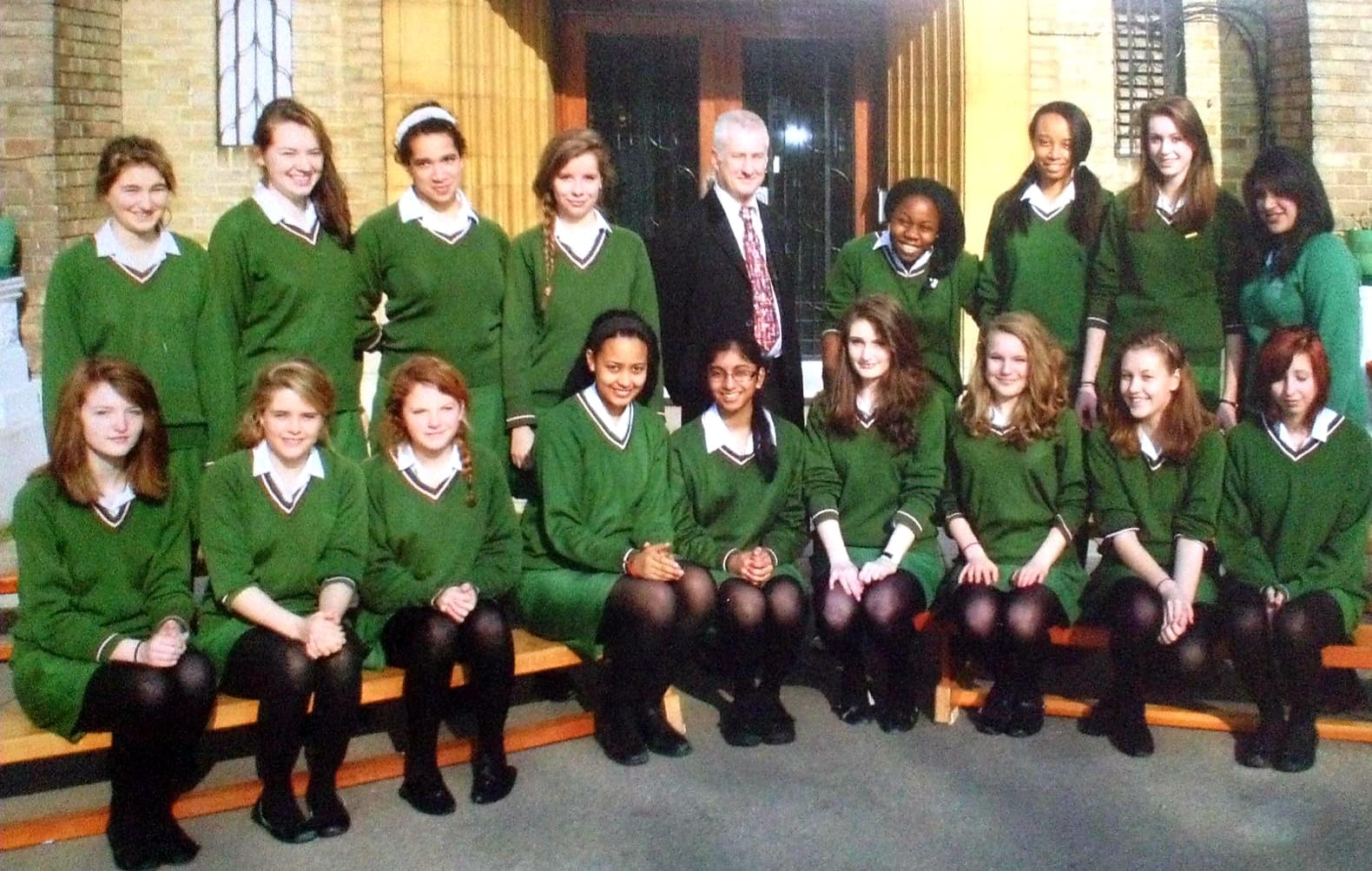

But then again, Black children in the west seldom enjoy the luxury of innocence for very long. And I’ll admit that my resilience-building experience prepared me well for secondary school where I was again the minority at an independent school – The Girls’ Day School Trust all-girls institution.

College was more problematic. My cousin was gunned down in 2010 in a case of mistaken identity. He and I were very close. I became depressed, anxious and vulnerable. I was in need of support and my attendance waned. Instead of offering pastoral care, the sixth form’s response was to kick me out. I was told by the head of the sixth form that I’d never amount to anything. I taught myself the A-level syllabuses and got the grades I needed. I adapted again for adult life, navigating various places of work.

At first, I saw attending an all-Black primary school as an inconvenient disruption to my normal programming – it was an annoying shift in routine. But the reality couldn’t have been more different; I was empowered to tune into my very being.

At Theodore McLeary school, students were happy, vibrant, neat, well moisturised and melanated beings – and that in itself meant we were subverting stereotypes in a world that we’d later discover could be so cruel to us.

This school provided a nurturing environment, for the most part, where teachers pushed many of us to become our best selves because when we excelled, so did the rest of us – this is the power of community. Our parents were also more engaged and could liaise with staff in Jamaican patois at parents evenings.

Ms Thompson would praise me for my flair in English while insisting “you can and must continue to excel, you’re not even using a fraction of your brainpower yet. Keep going”. I used to deem her an insatiable woman until I realised later on what true love looked like.

Speaking to my mum and aunty recently, they both confirmed why they decided to enrol their children at that school. They thought we’d stand to thrive in a supportive, welcoming and familiar environment – these brilliant women were absolutely right.

I recall my state primary days with some fondness. It wasn’t all bad. As a Black child, I adjusted to the status quo and accepted that achievement was a mere possibility. At Theodore McLeary, achievement was required. Therein lies the difference between the two.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks