Kevin Pietersen's fate is that of any maverick

Whether it be cricket, politics or the arts, picking the star who doesn't take direction is always a gamble

Like many another sports fan, I suspect, I stopped watching Test cricket from the moment the England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB) decided to take the Murdoch shilling and sell the broadcasting rights to Sky. But there was a glorious swansong, on holiday in France in 2005, when I discovered that the TV in our rented cottage was able to pick up terrestrial UK channels. It was the summer of Kevin Pietersen’s momentous England debut (473 runs in five matches at an average of 52.5) and, for a sofa-bound afternoon there in the Dordogne, my nine-year-old son and I sat and admired the spectacle of KP – big, brash and ebullient – doing the business in the final Test, a routing of the spavined Australian attack in which he smote no fewer than seven sixes and ended with a score of 158.

Enquiry revealed that, even then, in his mid-twenties, Pietersen could be filed under “maverick” – the most ominous of all professional categorisations whether you are a sportsman or woman, a politician or something as innocuous as a writer of poetry; and in cricket, shorthand for wayward genius, the mercurial talent who may very well score a century but is quite likely to run out three of his colleagues in the process. In a week when KP’s services have definitively been dispensed with by the cricketing authorities, the time-line compiled by the newspaper sports sections has all the evidence neatly marshalled. The derogatory texts about his captain; the charges of “disconnection” from long-suffering teammates; the score-settling autobiography – it is all as incriminating as the bundle marked “Swag” hung over the bank robber’s shoulder.

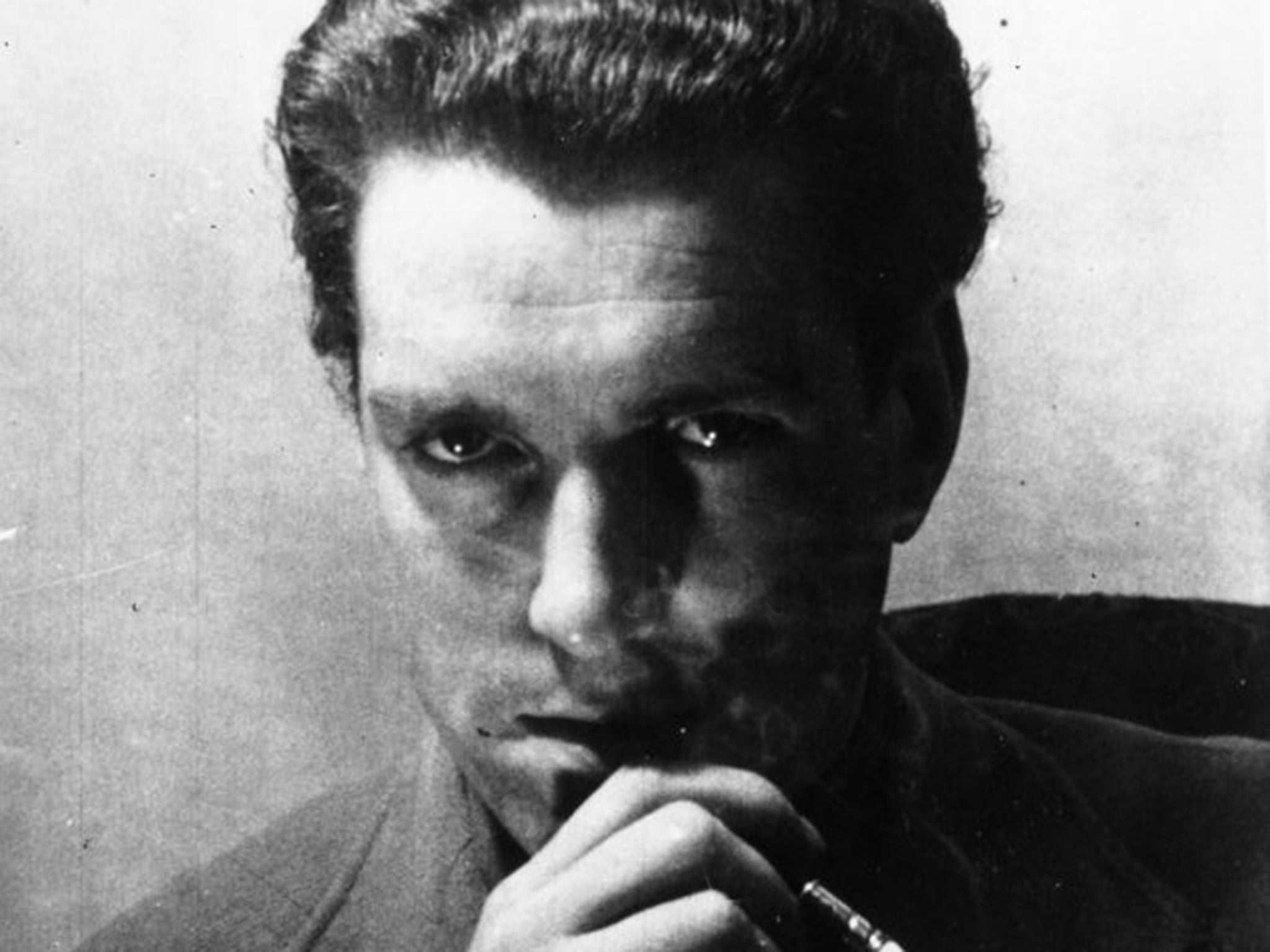

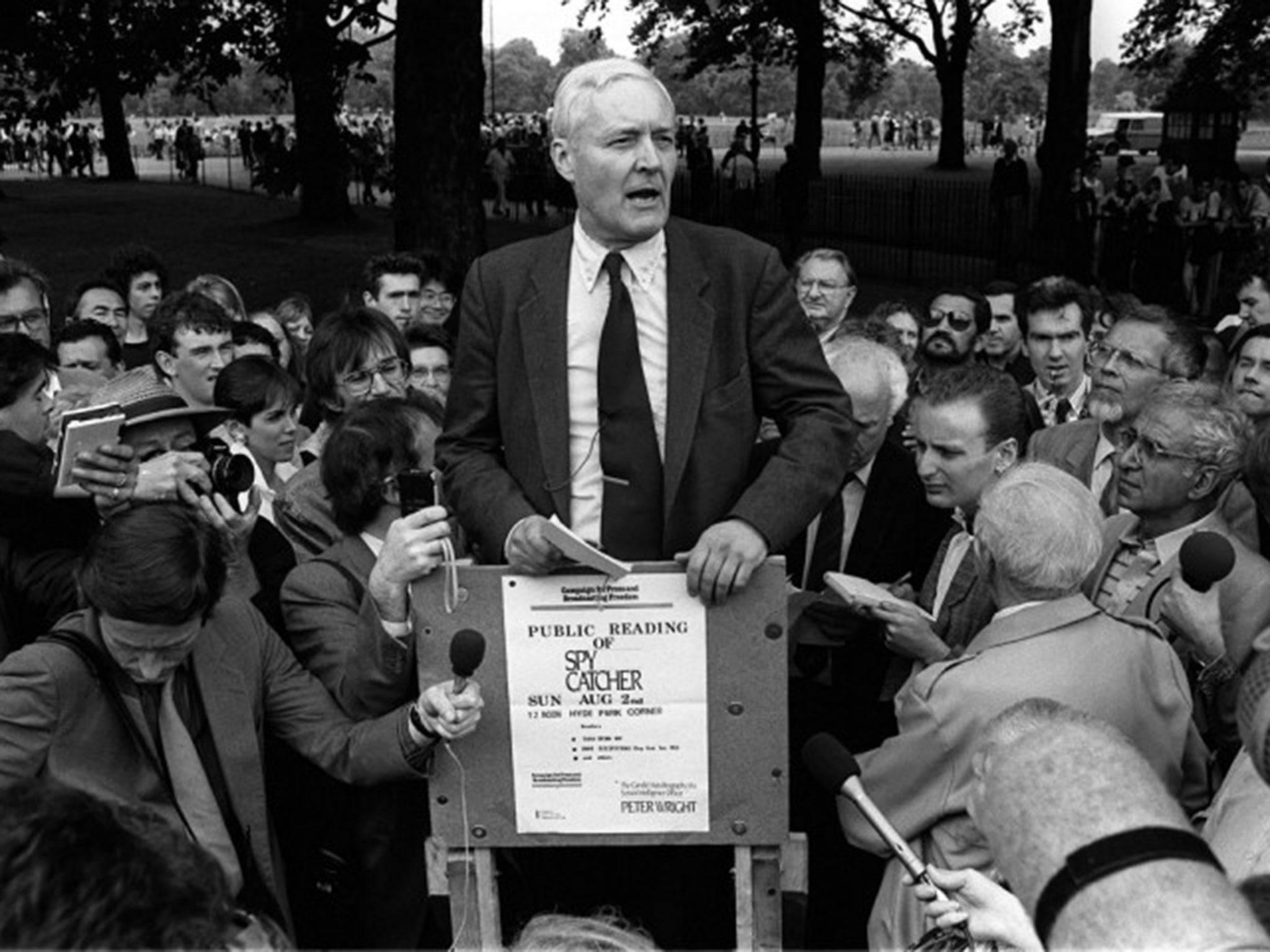

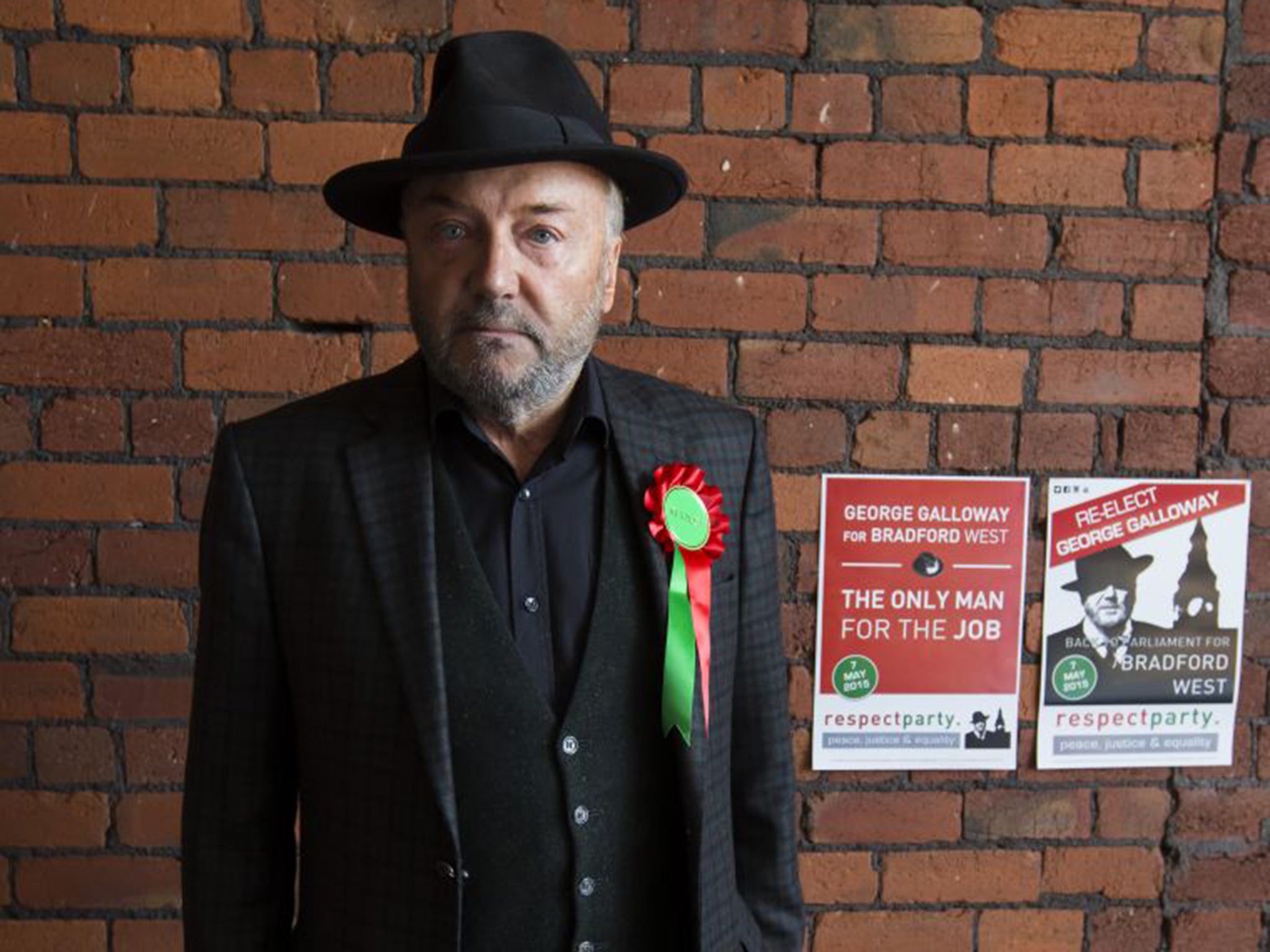

As the Pietersen case demonstrates, the “maverick” has always occupied a deeply ambiguous role in our national life. As well as the maverick sportsperson (QPR’s Joey Barton, for example, who accumulates red cards as rapidly as he produces quotations from Nietzsche), there have been maverick parliamentarians (Tony Benn, say, or Alan Clark, and most recently George Galloway), maverick artists (Dylan Thomas, whose centenary is currently being celebrated with all the respect due to a man who wrote some of the greatest lyric poetry in the language while contriving to drink himself to death) and enough maverick musicians to fill several commemorative editions of the New Musical Express. The ambiguity can be glimpsed in their ability to rack up fans and disparagers in equal numbers, but it can also be observed in the endless tightrope walk that lies ahead of anyone – any manager, party leader or editor – who decides , generally after much soul-searching, to bring a maverick on board.

Naturally, the defining characteristics of the maverick reside in talent. This is generally prodigious but also unorthodox: the goals scored from impossible angles; the shot struck to the boundary that, hit by anyone else, would have ended up in the hands of mid-on. But accompanying the talent comes a whole roster of warning signs. Mavericks, to particularise, are never likely to be team players: like Sir Oswald Mosley, they are capable of leaving one political party for a second and then founding a third. The idea of accountability is mostly beyond them. And to lack of responsibility for their actions can be added an almost paralysing consciousness of their own rectitude, a conviction that the only person marching in step is them. By far the funniest thing about Tony Benn’s garrulous diaries from the 1980s is the artless sincerity of their tone. He cannot see why his attacks on bygone Labour governments of which he was a part should so enrage his former colleagues – just as, 10 years before, he seems never to have got his head around the concept of collective cabinet responsibility, and the idea that he is being disloyal never occurs to him.

With consciousness of rectitude, inexorably, comes erratic behaviour. When not scoring a hat-trick, the maverick soccer player is odds on to get sent off in a cup final. The maverick journalist, on the other hand, is quite likely to disappear without trace for three months, leaving half a dozen commissions unfulfilled. Worse even than this is the logistical mess that mavericks tend to create around them: the Sargasso Sea of obligation and dependency in which even those trying to help end up being choked. Anthony Powell’s memoirs, for example, recall the occasion in the 1950s in which, when employed by Punch, he tried to assist the legendarily maverick writer Julian Maclaren-Ross by giving him reviewing work.

Constitutionally hard-up, and always one step ahead of the debt collectors, while at the same time producing lively and imaginative journalism, Maclaren-Ross threw the everyday life of the magazine into chaos. When his regular visits to the office to collect books became known to his creditors, a covey of bailiffs started to collect on the doorstep, to the point where Punch’s owner, his own progress impeded by a mob of duns, demanded that he be fired. Powell found himself placed in the quandary of all sponsors of maverick talent. Do you encourage someone who, on his day, is better than anyone else or settle for a quiet life? Do you pick the solid and reliable performer ahead of the unpredictable genius on the grounds that, if the former fails, he will, at least, do it unspectacularly?

For the maverick, when he – and the evidence of sport, politics and art suggests that it is mostly he – fails, there are no half measures. It is either the Champions League final or the Priory, the government front bench or the ignominious election defeat. George Galloway’s, it might be said, is a classic political maverick’s trajectory: the vivid personality; the spectacular falling out with his chieftains; the dizzying rebirth; the equally dizzying collapse. Galloway, too, possesses another maverick characteristic, which is acute self-consciousness. The majority of mavericks positively glory in the status of being “a bit of a rebel”, “an outsider” or someone who “won’t toe the party line” – statements that, for all their conviction, tend to infuriate the people forced to work side by side with them on a daily basis.

All this might suggest that mavericks are to be avoided, a drain on corporate resources and ripe to be dispensed with. Nothing could be further from the truth, for every institution, sports team or artistic tradition needs shaking up every now and then. The maverick tradition runs through British politics like a vein of quartz through a rock, although one might want to point out just how precarious are its chances of success. After all, had it not been for the Second World War, Winston Churchill – the acme of the maverick politician – might have spent the last two decades of his parliamentary career on the Conservative back benches. The best kind of political maverick, it might be said, is the Frank Field kind – Field having spent the past four decades following his conscience and the interests of his Birkenhead constituents without troubling himself as to what his party leaders think of him.

In general, though, the maverick needs careful handling. He may head the averages, but there will come a time when he’ll let you down. He’ll miss the team bus. His copy will blow out of the taxi window. He’ll turn up drunk for a television interview. There is a wonderful scene in A S Byatt’s Babel Tower (1996), in which a government commission investigating English teaching in 1960s schools includes a maverick performance poet named Mickey Impey. Flamboyant and narcissistic, Impey has a terrific time disrupting the smooth running of the commission and drawing attention to himself. “If I had him in my class, I’d watch him,” one of his colleagues bitterly remarks. You imagine the ECB feels the same way about Kevin Pietersen.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks