Giants like Amazon are creating extreme inequality – so why is the UK so slow at regulating big tech?

While both the US and EU are taking action against the platform giants, no significant challenge to their power is on the horizon in the UK. Matthew Lawrence explains what steps could be taken

There has been one indisputable winner of the pandemic: the digital platform giants that increasingly occupy the commanding heights of our economy. The “Big Five” – Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Google – represent around 20 per cent of the market value of the S&P 500 stock market, and companies like Uber and Deliveroo are all worth billions of pounds.

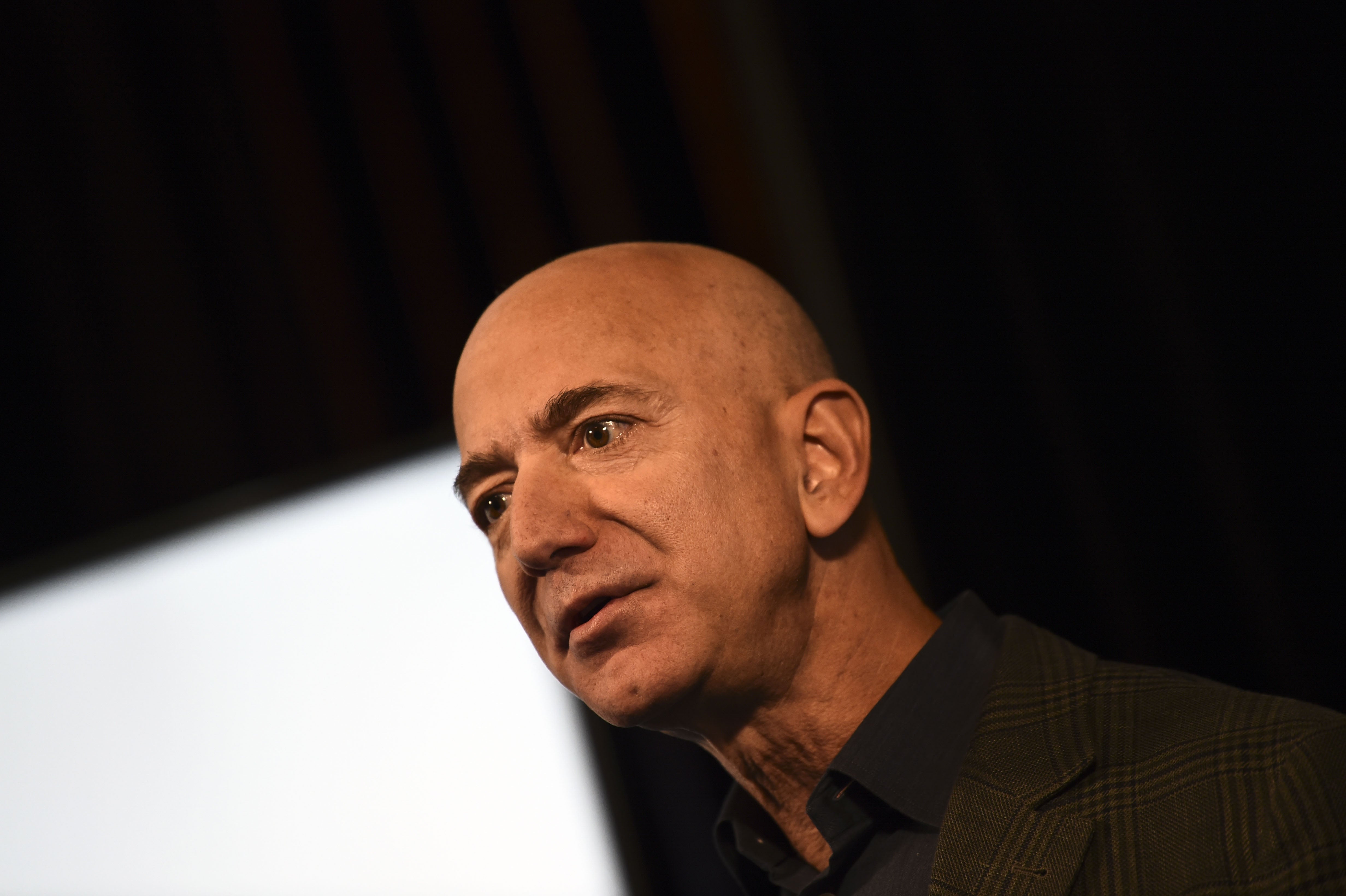

Unprecedented concentration of wealth is inevitably generating extreme inequality. While many have lost their livelihoods and income during lockdown, Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon, has seen his wealth surge by $90.1bn (£67.2bn) to a scarcely believable $203.1bn (£151.5bn) from March to October. This extraordinary concentration in wealth reflects the fundamental reality of the platform economy: these are among the most powerful monopolies in history, the rentier giants of the digital age.

The surging power of the platform giants is belatedly attracting the attention of policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic. The US Department of Justice recently filed an antitrust action against Google, the first step in what might be one of the biggest anti-monopoly cases of this century, while the European Commission has formally accused Amazon of breaking EU antitrust rules.

However, the UK lags behind. Though the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has conducted an impressive investigation into the digital advertising market, no equivalent challenge to the power of the platforms is on the horizon. What should such an ambitious agenda look like?

As the end of the Brexit transition period approaches, the politics of the platform - supercharged by the pandemic and geopolitics - will increasingly take centre stage. For some elements of the right, our exit from the UK is a chance to turn Britain into a digital pioneer of the 2020s. Famously, Dominic Cummings dreamed of using the tools of industrial strategy to build a trillion dollar British tech company; this appears fantastical, and more to the point, would only deepen concentrations of economic power in our unequal economy.

For the left, rightly concerned about the abuses and exploitation that lace through the platform economy, it is time to embrace a more systemic agenda, one that can transform who owns, operates, and governs these platforms and the data we collectively generate through them.

Antitrust action - the favoured tool of the US and EU authorities - is a useful tool for breaking up the concentrated power of the platforms and dispersing the terms of economic coordination. However, if designed poorly, it risks missing a key structural element of the platform economy: the in-built drive to monopolise is a feature, not a bug. This is partly because of powerful network effects, which occur when the value derived from using a platform depends on the number of other users using it, and which incentivise concentration and consolidation. Meanwhile, dominant platforms collect and analyse data generated by platform users to cement their competitive advantage. Any rivals that grow too threatening can be quickly acquired and incorporated.

The challenge is to liberate the democratic and enlivening potential of the platform from the logics of concentrated corporate ownership and profit maximisation. We know platforms can help us connect, communicate, and play. But we can also re-engineer them to operate without ubiquitous surveillance, counteract “fake news” and extend freedom of speech, and create more equal and democratic forms of collaboration. Three steps would mark a more ambitious agenda.

First, a new era of democratic data management. Decisions on whether to collect data, what data to collect, and how data can be used should not be left in the hands of private corporations or the state as presently constituted. Rather, new democratic and multi-stakeholder organisations and approaches are needed that give users and citizens real control.

Second, platforms that are deemed to be monopolies should be regulated as public utilities, limiting their power. This would be one way to rebalance risk and reward between companies, users, and society. And instead of data being privately enclosed, we should build a data commons, where data is carefully stewarded to protect rights and boost inclusive innovation.

Finally, we need to rebalance power in favour of workers in the UK and beyond. Fundamental to this must be a new deal for all workers that guarantees rights from day one, collective bargaining introduced to negotiate the terms of work on platforms, and a living wage for all.

Taken together, it is an agenda for a digital future that is democratic and equitable by design.

Mathew Lawrence is the director of the think tank Common Wealth and co-author of “A Common Platform”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments