Why I got emotional over the Alzheimer drug breakthrough – it brings true hope

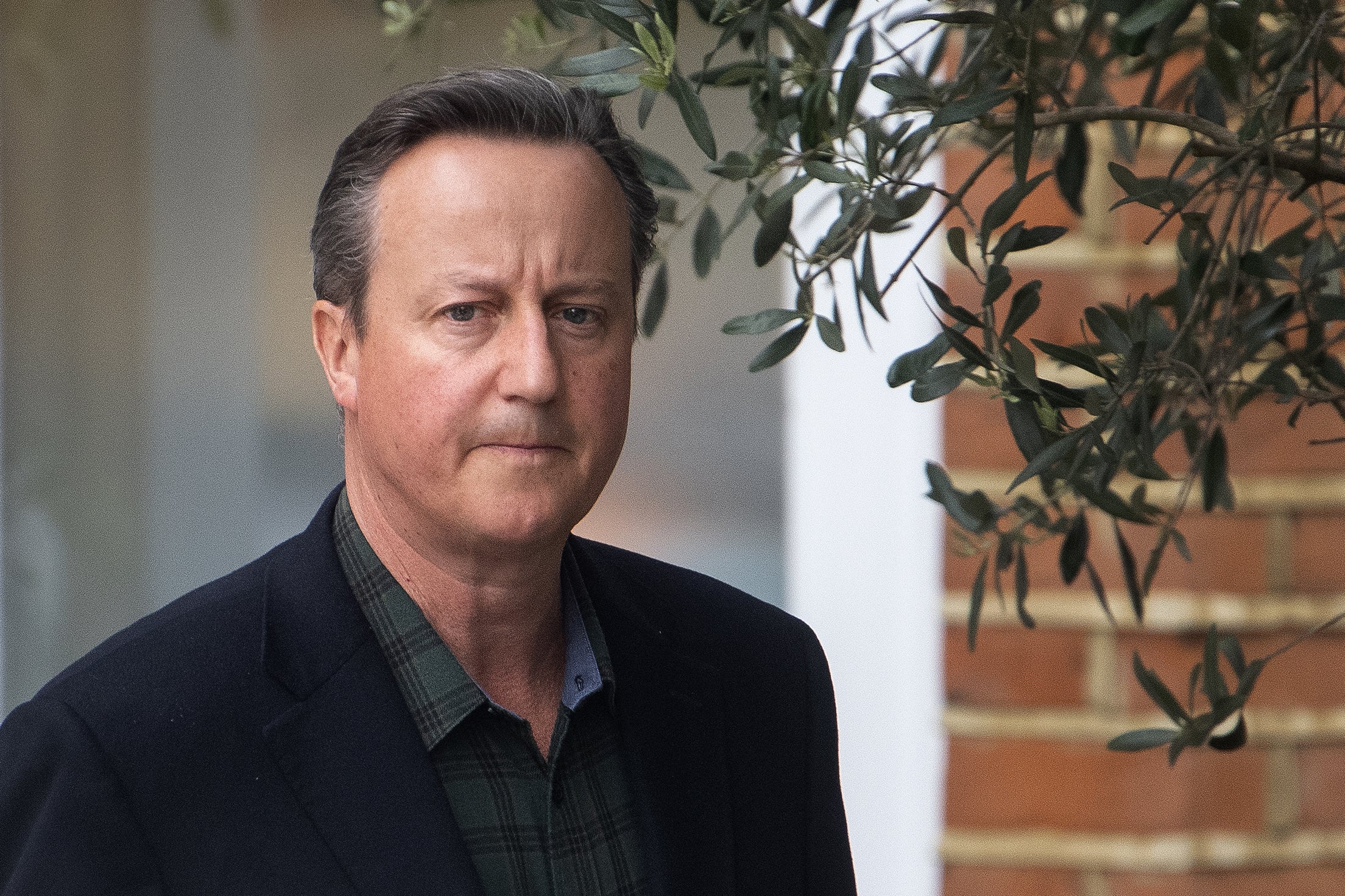

Terms like ‘breakthrough’ and ‘turning point’ should always be used with caution, writes David Cameron. But in the case of the dementia ‘wonder drug’ donanemab, they are justified for the chance they give sufferers the chance to live well – and with dignity

It is not often that I get emotional watching the evening news. This week was different. Monday’s lead item featured a man living with Alzheimer’s, who is currently taking part in a global trial to find a treatment for the disease. “I’m one of the luckiest people you’ll ever meet,” he told the reporter, as it was announced that the drug he’s been on for two years, donanemab, can slow the pace of cognitive decline by a third.

Seeing the man and his son being interviewed was particularly poignant because that is what first sparked my interest in the issue: meeting people living with dementia and members of their families.

As an MP, I saw care homes in my constituency growing ever larger to cater for the growing number of people with diseases such as Alzheimer’s. I would visit regularly, often speaking to the heartbroken sons and daughters who were watching their mothers and fathers slipping into a world of darkness.

Back then, society seemed resigned to this problem. Many considered dementia as an inevitable part of ageing. The concept of treatments and cures seemed like a pipedream. But I was convinced it didn’t have to be this way.

It was why I doubled dementia funding as prime minister and made it a research priority. I put the issue on the global agenda when Britain hosted the G8 and have made it my focus, post politics, as president of Alzheimer’s Research UK. After seven years in the role, I can say there has never been so much excitement at the charity as there is at the moment.

So what exactly does donanemab do? The drug, administered by a monthly infusion, works by removing the build-up of amyloid protein, which many experts believe to be a cause of Alzheimer’s. It has been shown to slow cognitive decline, just as the drug lecanemab did at the end of last year.

These are, of course, early days. There are serious side effects that must be studied. The improvements are, as is to be expected at this stage, modest. Donanemab only applies to Alzheimer’s, one of several diseases that causes dementia. It is not a cure.

But for the first time we are seeing drugs in late-stage clinical trials that tackle both the symptoms and underlying causes of one of the diseases that cause dementia. Terms like “breakthrough” and “turning point” should always be used with caution. But in the case of donanemab, they are justified.

Not only will it allow people to live more independent lives for longer. We now know that we’re onto something with these amyloid plaques. And more than that: success breeds success. With such breakthroughs, interest and funding follows.

It feels as though the science, the understanding and the incentives are now falling into place. And in a country of 60 million people, where nearly a million have dementia, the incentives are only increasing.

What happens next? The holy grail, from what I can see, is a preventative medicine that can be taken at an early stage and help prevent these proteins building up in the brain in the first place. I’ve long referred to it as “a statin for the brain” – something you can take every day or every week in order to reduce your chances of getting a disease that causes dementia, just as we do with statins and heart disease.

Added to this, researchers and pharmaceutical companies are making significant advances when it comes to a potential blood test for dementia. That is the breakthrough that will go in tandem with treatments like this: a simple and accurate diagnosis. We are still some way off going to your GP, having a routine test, and then being prescribed something – like a statin – but the prospect of this happening really is in sight.

It is nearly 10 years since I stood in front of an audience of G8 leaders we were hosting in Northern Ireland and launched a global fightback against dementia, “not just on finding a cure for dementia but preventing it, delaying it, and critically – helping those who live with dementia to live well, and live with dignity.”

Over the past decade we have inched closer towards all those goals. Resignation has been replaced by hope. As the son of the patient on the TV news put it, “I never thought I would see my dad so full of life again. It was an incredible moment.”

David Cameron was the prime minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016, and leader of the Conservative Party from 2005 to 2016

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks