A year after the referendum, Scotland could actually be closer to independence

In Scotland today, far from being buried by last year’s no vote, the independence debate is surprisingly omnipresent

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Exactly a year ago today, Alex Salmond’s aides were putting the finishing touches to the text of what they hoped would be an historic victory speech. “In the early hours of this morning, Scotland voted Yes,” the then First Minister was to begin. “We are a nation reborn.” It was not to be; instead, the veteran Nationalist leader conceded defeat.

Yet in the memorable and unpredictable aftermath of that result, it was the SNP that was reborn, witnessing an influx of new members and remarkable electoral success.

And despite a decisive majority of Scots opting to remain part of the UK, the two-year referendum campaign normalised the idea of independence. In Scotland today, far from being buried by last year’s no vote, the independence debate is omnipresent. It is the prism through which every single political development – even the recent election of Jeremy Corbyn – is now viewed.

Continuing analysis of what the referendum result meant competes with new speculation as to when a second ballot might take place. Some have called it the “Ulsterification” of Scottish politics, the eclipsing of domestic politics by a Unionist/Nationalist frame (albeit without the violence). The Prime Minister and his Scottish Secretary repeat that another ballot isn’t necessary, but no-one seriously believes them.

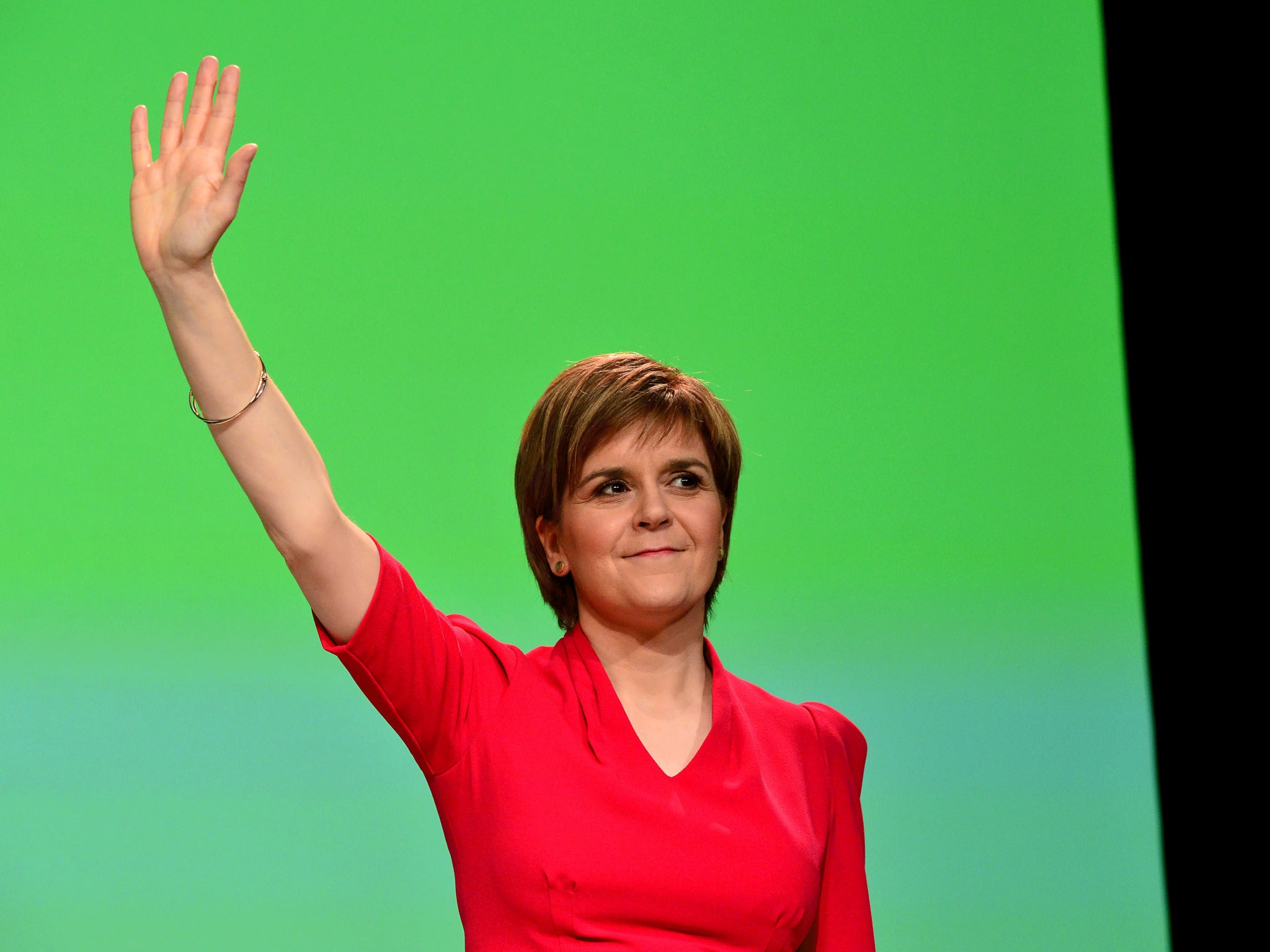

This week First Minister Nicola Sturgeon will address her MPs and MSPs at an anniversary event in Edinburgh. She and the party have begun beating the independence drum more loudly, partly a response to Corbyn’s victory, and also because polls now indicate support for independence is rising.

Consequently, there has been little Nationalist analysis around the reasons for defeat last September. Academic work points to doubts about the economic consequences (which crystalised around the proposed “currency union”), but Alex Salmond prefers to blame a series of straw men: the “biased” media; “scaremongering” by opponents; even, at one stage, nervous elderly voters.

By contrast, the parties comprising the Better Together campaign have begun indulging in bitchy self-flagellation. Leading figures within the Labour party have lined up talk of their failures, tactically and politically. An atmosphere of gloom pervades. Many believe a second referendum is not only “inevitable” (Salmond’s preferred adjective), but will be roundly lost by demoralised Unionists.

The Prime Minister hasn’t escaped his share of the blame. Although his “red line” that the referendum comprise only one question was viewed as a triumph at the time, it looks shortsighted in retrospect. Had he embraced Salmond’s offer of a “second” question on “more powers” some believe, with good reason, the independence option would have been crushed beneath a swarm of voters embracing a constitutional Third Way. Better still, had David Cameron used that as an opportunity to reboot the British constitution more broadly, tackling the House of Lords and the English Question, Unionists would have been able to fight the referendum with a “positive” vision of their own. It wouldn’t have been easy, but the dynamic would have been completely transformed.

If the insistence upon a single, polarising question was a miscalculation, then the timescale of the vote amounted to carelessness. I was present at the Scotland Office on Whitehall when, in early 2012, Cameron casually mentioned being “relaxed” about the SNP’s preference for an autumn 2014 plebiscite. The colour drained from his advisers’ faces as an important negotiating point was discarded.

Thus, the pro-independence lobby was able to campaign both positively and over such a long period that it had time to articulate its (hitherto vague) vision like never before.

Following a close shave in Quebec in 1995, the Canadian federal government sold the benefits of remaining part of Canada much more passionately than Unionists have done over the past 12 months. Were such an effort to begin in earnest a year after the defining moment in modern British history, it might already be too late.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments