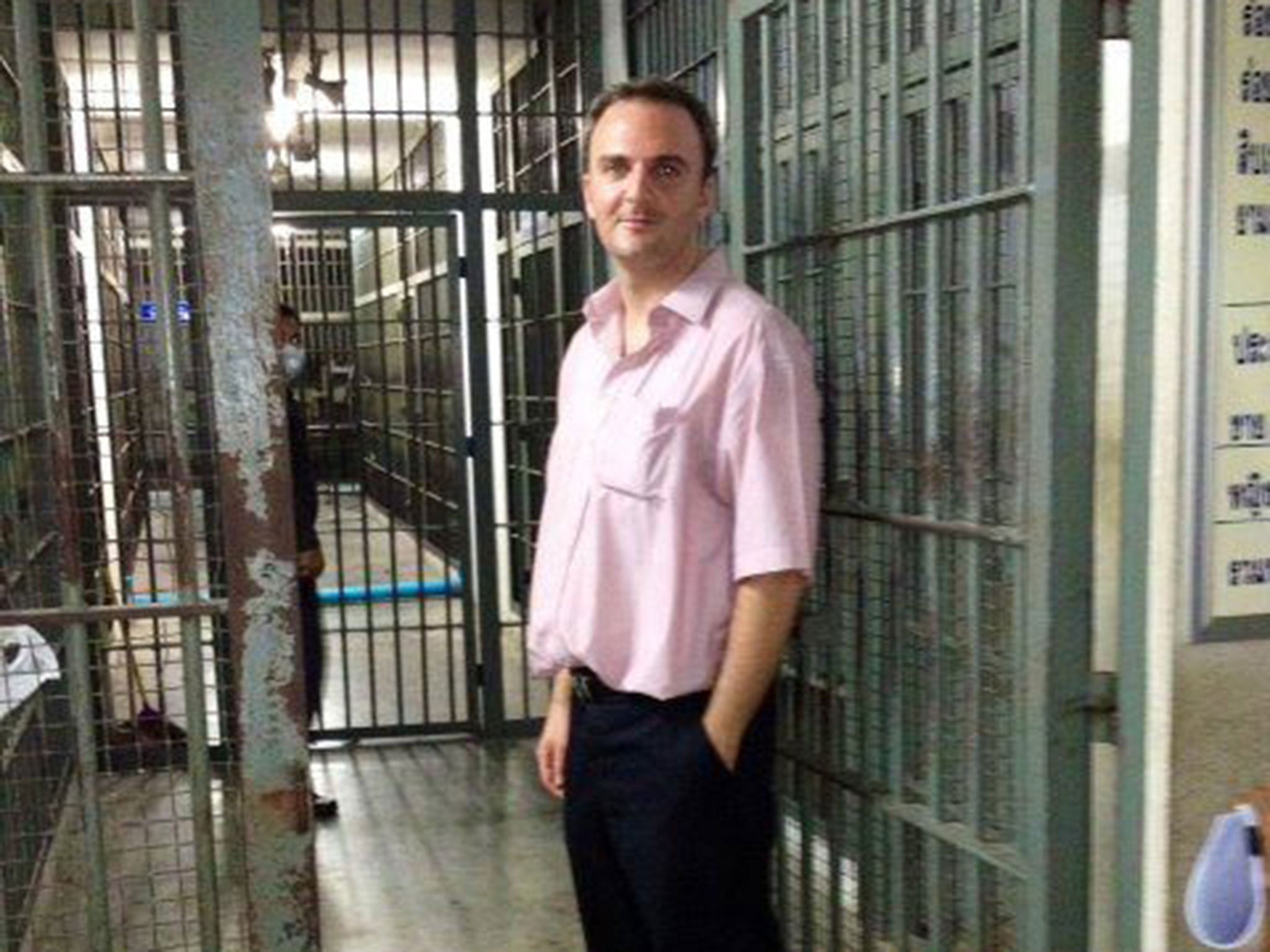

A man who changed the lives of hundreds faces years in Thai prison while our government drags its heels

Andy Hall, whose thankless work focused on exposing the disgusting conditions inside factories, deserves the full force of our government behind him

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I expected Andy Hall to sound jumpy when we spoke on the phone yesterday morning. He has just been indicted by a Thai court, and faces seven years in prison, on top of an £8m fine. The crime? In 2012, Hall met and interviewed workers at a factory belonging to Natural Fruit, a Thai pineapple-processing firm, for a report on their labour conditions. Disgusting, was the summary.

Natural Fruit denied the allegations and sued for criminal defamation. Thailand’s legal system is pliant, its government unconcerned with freedom of speech or labour rights. Yet Hall strikes a blasé note. Even a kangaroo court would struggle to convict on this evidence. “But if I were Thai or from Myanmar,” he goes on, “there’s a high risk I’d be dead”.

Little though they know it, anyone who has put a supermarket carton of “own-brand” pineapple juice in their shopping basket has some slight connection to Hall. He is not a foreign correspondent. Instead, for the past decade, the Lincolnshire-born campaigner has moved through Thailand and Myanmar, reporting on human rights abuses that rarely surface in the news.

He speaks the local language. He can switch from high to low circles. And his work proves the power of information: of the 60 factories Hall has investigated so far, the majority responded by improving their working conditions. That amounts to thousands of lives changed.

Natural Fruit, however, took the other route. Faced with Hall’s allegations of beating, exploitation wages, debt bondage and passport confiscation, the Thai firm decided to go after the messenger. Heavies keep a close eye on Hall. And, partly because he does not work for a newspaper, Natural Fruit feel at liberty to involve the law. “I’m a small guy, easily attackable,” he says. With employers taking fright, he has lost two jobs since the case began.

It is no secret that the number of foreign correspondents has fallen away with the rapid decline of newspaper budgets. The costs of employing them are relatively high, and the worthiness of their work is not always matched in terms of readership.

But, as they dwindle, so do the opportunities for powerless, exploited people to be heard in the West by consumers often unwittingly complicit in their abuse. In short, if you’re an illegal immigrant from Myanmar working in Thailand, the newspaper industry’s struggle to transition to a digital age is bad news. “From what I’ve seen,” says Hall, “reporters are ever more responsible for the whole of Asia. It’s too much.”

As a result, more of that region falls into shadow, and cheap pineapple juice (produced by child labourers) is known to the West only as cheap pineapple juice.

Thankfully, as fewer correspondents are made to cover more ground, a growing number of human-rights researchers are finding localised, specialist work. Human Rights Watch (HRW) now employs more field reporters than the corps of correspondents at both The New York Times and The Washington Post.

In the past year, the organisation has played a central role in encouraging the UN to deploy a peacekeeping force in the Central African Republic, contributed to China closing its labour camps and showed that Assad used sarin gas on the Syrian people. A round of applause is deserved.

Such victories are only made possible, it bears repeating, because of the bravery of researchers who receive little protection and less glory. For all the talk of defending human rights worldwide, the British government has been slow to back Hall up. Perhaps some explanation can be found in the fact that we import masses of poultry, fruit and vegetables from Thailand – goods “tainted by slavery”, Hall says.

It took the Foreign Office a long time to reach the conclusion – surely obvious – that the Oxford graduate is in fact a “human rights defender”, and so deserving of state protection. Consequently, an observer from the Embassy did make an appearance at his indictment this week. But that ought not to be the end of it. If the full muscle of the state will not weigh in on behalf of a national citizen, exposing the true cost of our cheap imports, what chance is there it will pay the slightest attention to Thai reporters and researchers also speaking truth to power?

Unknown, underpaid, and under threat, the likes of Hall strike me as almost perfectly heroic. As the people they report on deserve better, so do they.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments