Searching for Goya in the streets that made and inspired him

As his work comes to London, Jonathan Lorie visits the streets of Madrid that the artist once haunted

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“There’s a legend that Goya washed dishes in this restaurant,” Pepe Gonzalez says, uncorking a rioja to accompany the sizzling dish of suckling pig that has arrived at my table in the gothic dining room of the Casa Botin. “But we don’t know for sure. What we do know is that this is the oldest restaurant in the world, from 1725. He came to Madrid 50 years later, an unknown painter. Maybe he needed a job?” Gonzales shrugs.

Francisco Goya, the greatest Spanish painter of the Romantic era, is the reason I’ve come to Madrid. His magnificent portraits of Spanish society, from royals to ruffians, artists to aristos, will be on show this week in a major exhibition at the National Gallery in London, and I want to discover the world that inspired his work.

I thank Gonzales for a fabulous lunch and totter on to the cobbles of old Madrid. A stone gate leads into the Plaza Mayor, a classical square whose arcades hide ancient shops selling berets and cakes. I wander alleys lined with green shutters and iron balconies. Finally, in Calle Santiago I find a plaque marking the place where Goya lived at No 6. It’s a modest townhouse painted cream, in a pretty street filled with trees and cafés where children are playing – just as they do in his loveliest early pictures. I’m surprised at how modest this place is, for Goya became head painter at the royal court in 1789, with a fine salary plus expenses for a coach.

But he remained also a man of the people, never forgetting his humble roots as the son of a poor gilder in provincial Zaragoza. And his pictures show the life of the street as well as the court.

The high life that he knew can be found two blocks further on, in the Royal Palace. It’s rococo bling, a maze of rooms draped in silk and lit with chandeliers. The dining room has a table set for 50 guests. On a wall are Goya’s portraits of the king and queen, an ageing couple pictured as rather ordinary beneath the satins and medals – an old man with a vacant smile and his wife with a firm mouth who was said to run the show.

A different side of Madrid is seen in the royal chapel that Goya painted, a short walk down the river Manzanares. The Real Ermita de San Antonio de la Florida took him just four months in 1798, and he covered its walls and dome with images of ordinary people, some in rags, all being blessed by a monk in a brown robe. It’s an astonishingly democratic image, reflecting the age of revolution in which it was done. And below the dome lies the painter’s tomb.

I head back for lighter relief to my hotel, the Principal, on the buzzing Gran Vía. But en route I meet a procession emerging from a church, black-robed men bearing a statue of the Virgin Mary on their shoulders, women in mantilla headdresses weeping. Drums throb in the dusk. A crazed-looking boy shouts: “Viva la Reina, viva Maria!” It could be a scene from Goya.

Next morning I visit the royal tapestry factory where Goya had his first job in Madrid, painting charming images of rustic life that were woven into tapestries for the palaces. Amazingly, the looms are still in use – seven huge frames of wood where weavers toil for months to make replicas of his and other tapestries. The walls are hung with bright skeins of wool and silk; it can take nine months to make a square metre, costing around £9,000.

Designing for the palaces allowed Goya to catch the royal eye, and eventually he rose to be assistant director of the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando (the Royal Academy of Fine Arts). Today it’s still a painting school, but its grand rooms also house a museum with a fine collection of his works – smaller but less crowded than the nearby Prado, where everyone goes to see Goya.

Two rooms of his paintings here show his range, from heroic portraits of generals, politicians and society beauties, to more disturbing social comment in scenes of inquisitions, masked carnivals and lunatics raving in an asylum. The glitter and failure of the ancien regime is marked out in these rooms.

Downstairs in the Academy is something else. The Calcografia is a dim-lit space where the copper plates for Goya’s engravings line the walls. These come from his most famous and fearsome series: Los Caprichos, with their devastating satire of contemporary life, the Tauromaquia on bullfighting, and The Disasters of War, which document the horrors of Napoleon’s invasion of Spain in 1808. The prints from these are not on show much in Madrid, for conservation reasons, but some of them are in the library here, if you care to look. They foreshadow the terrifying “black paintings” of his final years, when war and age and possibly insanity had turned his art very dark indeed.

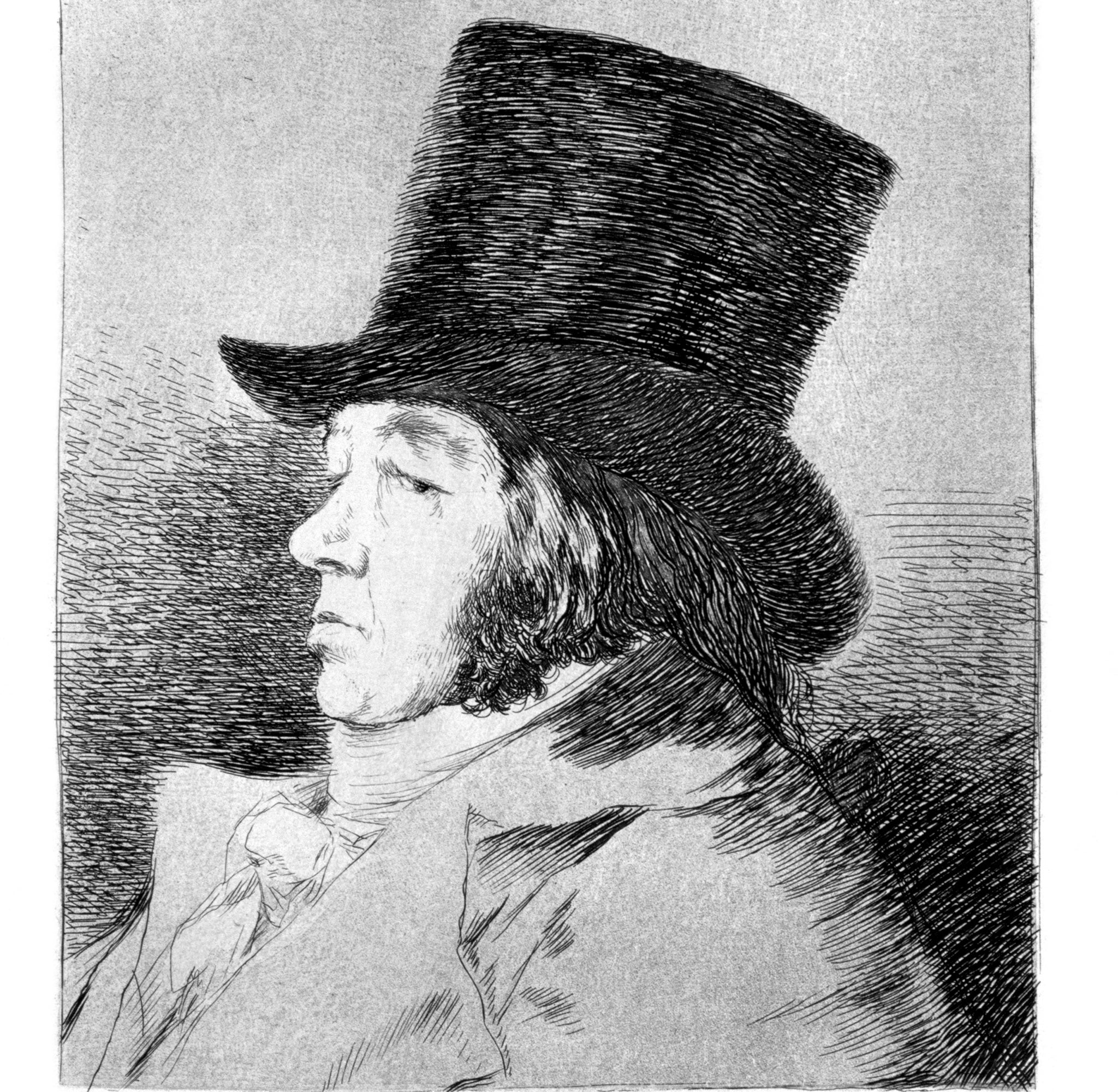

I retreat to a final watering-hole, established in Goya’s lifetime, the Casa Alberto of 1827. It’s the classic taberna of Madrid, its walls covered with pictures of bullfighters, its ceilings heavy with chandeliers, its zinc counter spilling over with food. Over a glass of chilled fino, I mull on a final painting from the Academy: Goya’s full-length self-portrait, standing at the easel, staring at the viewer, his eyes deep brown and unflinching.

Fixed around his hat is a circle of candles, for working in the night: a symbol, perhaps, of his role as an artist. He’s dressed in black, but behind him there’s a window shedding light.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments