A beach airport, secret whisky stashes and the world’s prettiest proposed nuclear waste dump: Walking Scotland’s island of Barra

It may be best known for its unconventional landing strip, but strolling around the Scottish isle reveals a catalogue of curiosities

There are some places you expect to see an aircraft - say, for argument’s sake, on an airport runway, or in the sky. Then there are places you do not expect to see one, such as on a beach. Yet that is exactly where the Twin Otter aircraft is, bumping along over the sandy ridges of Barra’s Tràigh Mhòr, its fuselage wobbling in the wind. Then, as if picked up by an invisible hand, it lifts into the air, dips and achieves elevation almost vertically - resembling a helicopter rather more than you think it ought to.

I’ve timed my walk on Barra, the most southerly of Scotland’s inhabited Outer Hebrides islands, to catch the spectacle of what is claimed to be the world’s only scheduled beach landing by a commercial aircraft. The vast sands of Tràigh Mhòr are laid out before me: the tide at its lowest and the water’s edge so distant and so shallow that it’s not actually visible.

The flight has proved to be quite a social occasion and a dozen or so onlookers begin to pick themselves up off the dunes, packed lunches eaten, and fold up their blankets. Cockle pickers are already scuttling onto the beach, harvesting up delicacies for the island’s restaurants.

I grab a cup of coffee at the airport café, which is almost as much of a revelation as the sight of the aircraft on the beach. Unlike almost every other airport café I've visited around the world, it is friendly and good value. The coffee is prepared from what is advertised, tongue firmly in cheek, as: “Barra’s only espresso machine imported from Birmingham.”

I had planned to continue along the small road towards the Eoligarry peninsula. Yet with the tide out, a beach walk, with the boots off, is irresistible. I strike out, contouring between the land and the nearby island of Orasay. I then clamber up onto dry land via a grassy slipway near the Eoligarry jetty and make my way through a series of utterly empty lanes to the 12th-century church Cille Bharra, or St Barr.

It’s a plaintive spot, a gaggle of ruined buildings, with a lonely but still consecrated chapel overlooking the Sound of Barra. In the adjacent graveyard is the resting place of Compton Mackenzie, author of Whisky Galore, the epic, if somewhat embellished account of how islanders on neighbouring Eriskay tried to secrete away several thousand bottles of whisky recovered from a stricken ship in 1941 (Mackenzie’s old house still stands, at the south-west end of the beach road overlooking Tràigh Mhòr). The chapel itself houses medieval tombstones that once covered the graves of the ruling Macneils.

Leaving the chapel behind I head further north along a single track road, passing what must be one of the most remote bus stops in the United Kingdom. (Amazingly, a bus makes it out here up to four times daily - though some services are request only.) Continuing alongside another vast and empty beach, Tràigh Sgùrabhal, I then begin an uneven climb through tussocks of cattle-cleaved turf up the flanks of an Iron Age hill fort, Dun Scurrival.

The ruins are modest – or, if one were being blunt, “collapsed” - but the views are the reason for clambering up here. I’ve soon enough height to enjoy the first views of the dune-swept back-to-back beaches, or tombolo, that cuts between Tràigh Mhòr and the west-facing Tràigh Eais (this is one of only a handful of tombolos in the UK).

Just offshore is the island of Fuday, once proposed as a repository for the UK’s nuclear waste. Uninhabited and separated by a kilometre of sea from Barra, Fuday comprises gently sweeping moorland and a crenulated coastline with small beaches popular among kayakers for mooring. For such a serene place of wonder to ever be considered to pick up the UK’s unwanted waste seems remarkably unfair. The plan was officially dropped but locals, mindful of the renewed political vigour with which the UK appears to be embracing nuclear power, keep a wary eye on developments.

Ahead, separated by a short dip, is the more daunting summit of Beinn Eolaigearraidh Mhòr. A glance at the map reveals it is barely 100 metres high, but from near sea level it looms more forbiddingly. I reach it more quickly than I expect and am rewarded for the modest exertion by one of the best views of the Outer Hebrides.

The tombolo stretches out for almost two miles. I can finally pick out the water’s edge and behind that, Eriskay and the ridge of hills that runs up another beautifully isolated island, South Uist. In the foreground is the Sound of Barra, the seabirds still gathering: autumn is a fine time to see the gannets plunging into the sea, stocking up ahead of their winter ventures into the Atlantic, and geese and swans in retreat from the high Arctic.

It’s becoming a day for beach walks: I drop down the hill to Tràigh Eais and feel its dazzling white sand between my toes. At the far end, I turn inland through the dunes and emerge above Tràigh Mhòr. The flight to Glasgow has long departed and so have the onlookers, yet the café, far from returning to its slumbers, is buzzing. Time for another coffee, and a slice of cake.

Outer Hebrides, The Western Isles of Scotland, from Lewis to Barra by Mark Rowe will be published by Bradt in April 2017. RRP £14.99

Travel essentials

Walking there

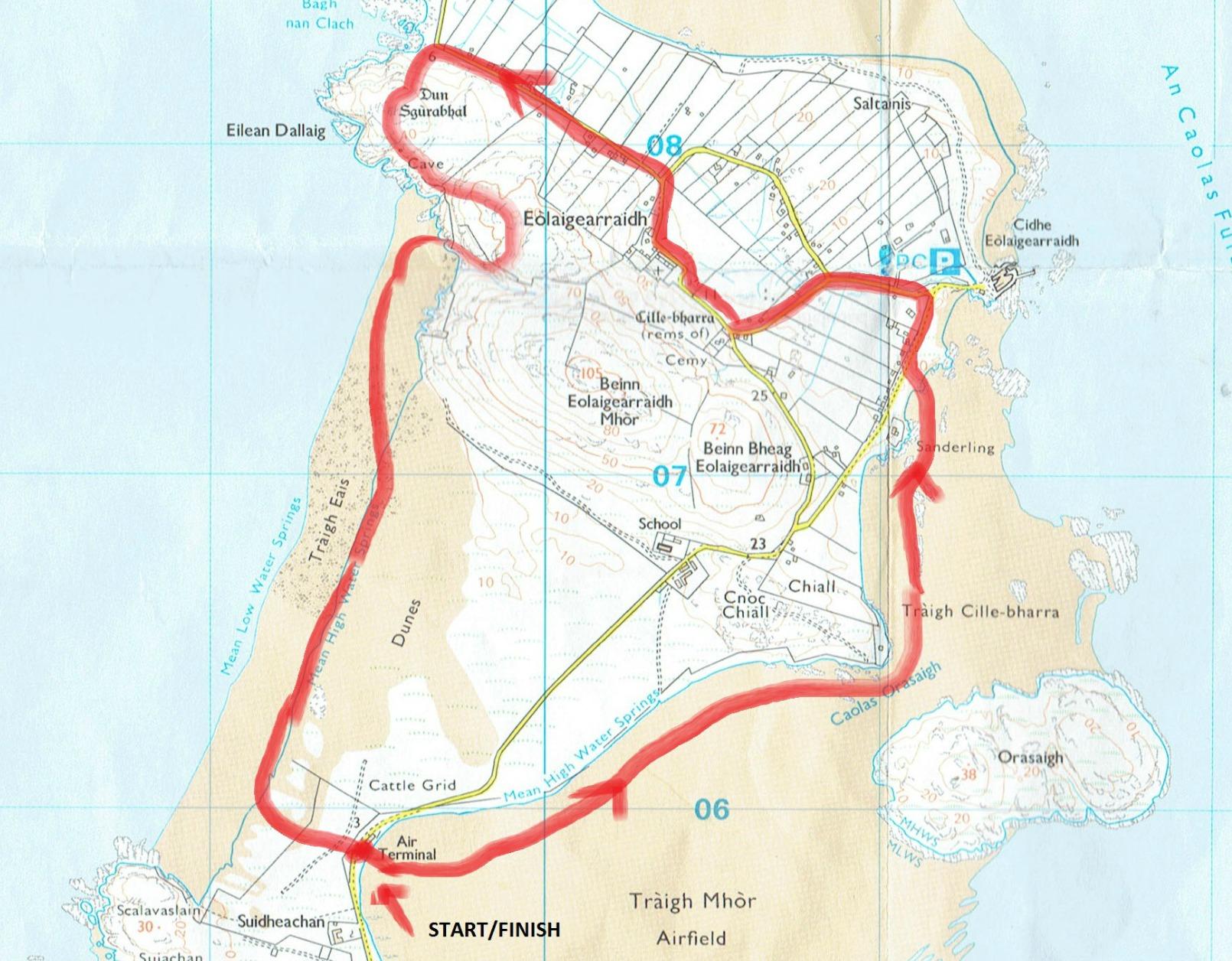

This five-mile route, taking around two-and-a-half hours, begins and ends at Barra Airport. Check tide times to walk at low tide. Full walking directions below.

Getting there

The W32 bus (cne-siar.gov.uk/travel/busservice) runs between Barra’s main village of Castlebay and the airport. Otherwise park with care near the airport (on the verges beyond the yellow lines either side of the airport; do not park in passing places. In the unlikely event there is no space you can park at Eoligarry jetty and start and finish the walk from there).

easyJet (0330 365 5000; easyjet.com) flies from Belfast, Bristol, Jersey, Luton, Stansted and Gatwick to Glasgow; Loganair, a franchise of Flybe (0871 700 0535; flybe.com) flies twice daily most days from Glasgow to Barra.

Staying there

Friendly B&B Croit na h-Abhainn Borve (01871 810 624; no website), three miles from Castlebay, has doubles from £60 per night.

More information

Walking directions

Head east from the airport along Tràig Mhòr, keeping Orasay island on your right. When you approach Eilogarry jetty, look for the slipway up onto the road and turn right. At the first junction turn left and walk towards the chapel, which is clearly visible. At the chapel continue along the road heading north-west until it bends sharply right. Go through the gate on the left and climb Dun Scurrival. Continue ahead, using fingerpost waymarkers to the summit of Beinn Eolaigearraidh Mhòr. Drop down to the west-facing beach. Walk south; near the far end make your way through any of the gaps in the dunes and across open ground to the airport road.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks